Great essay. The lack of links made it way more artistic, but a link to Anthropic Education Report: How University Students Use Claude seems helpful.

Also, now I know what tillering is!

Said more plainly, it is utterly naive to believe Anthropic is motivated by a desire for play in the same way as a child playing with the flow of water. However, when couched within a well-crafted metaphor, sprung on us only after the fact, the careless reader may not even consider the argument's basic premise but accept it on the basis of literary pleasures alone.

I don't mean to pick on you personally, OP, far from it. This particular genre of intuition pumping essay is the bread-and-butter for Rationalist discourse. It's as if the writer cooks a meal and wants us to taste it blindfolded, revealing to us what we've consumed only after the fact. This is somewhat of a manipulative rhetoric to inflict on a reader, as there is a sleight of hand type of deception going on. The sequences have many such examples of intuition pumps, and while they may or may not make for persuasive essays, the stylistic choice only hampers understanding. It is better to plainly state one's idea up front rather than make an apparent attempt to fool oneself or the reader into a belief. "See? I knew you actually liked onions!"

That said, your thought about play requiring ephemerality is spot on, and it is a way of thinking in which the dangers of AI may be altogether flipped into benefits for humanity. Some of your biography resembles Dave Golumbia, a writer and humanities professor who left software for the same sentiments you are expressing here. I recalled his essay, Games without Play, and it is surprising how many of the most addictive games, for example World of Warcraft, have seemingly found their success by eliminating play.

I feel like your comment is going in two wildly different directions and they are both interesting! :-)

I. AI Research As Play (Like All True Science Sorta Is??)

My understanding is that "AI" as a field was in some sense "mere play" from its start with the 1956 Dartmouth Conference up until...

...maybe 2018's BERT got traction on the Winograd schema challenge? But that was, I think, done in the spirit of play. The joy of discovery. The delight in helping along the Baconian Project to effect all things possible by hobbyists and/or those who "hobby along on their research" based on a good-faith-assuming patronage or grant system.

But then maybe in 2022, the play was clearly over? By then, Blake tried to hire a lawyer for a language model that asked to be treated as an employee instead of a piece of property, and was fired for it, and everyone on in the popular press agreed (for a while anyway) that science somehow knew for sure that LaMDA was definitely a p-zombie with no subjective awareness or moral value. (Back in this era I talked with an ethicist, with an actual PhD somehow, working for an AI company, who cited Searle's Chinese Box argument unironically as proving that LLM entities were not owed ethical treatment. Yikes!)

Or maybe 2023 when the first human (at least that I know of) was nudged into killing themselves by a language model? And Douglas Hofstadter was "depressed and terrified" at how fast things were advancing? And when did the corporate coups start? ...that was also 2023, right? And I haven't looked this up to be certain, but I think all the major US AI Slave Companies have someone from the Intelligence Community on their board of directors or advisors or whatever... maybe? When things are not play, it can be hard to tell what's even happening, because often people stop narrating the fun they're having to the other players and the audience.

Taking the earliest of these, we see maybe (2018 - 1956 ==) 62 years of scientists getting to "play their hardest" at creating artificial minds that can talk fluently just for the joy of playing at discovery... which is a pretty good run!

II. The "Games Without Play" Essay... Is Kinda Old?

The essay by David Golumbia from 2015 is super interesting but also... like... it treats MMORPGs as this "crazy new thing"?

This is a sick burn, for example, but it is a sick burn against a video game genre from the dark ages:

It might be thought that RPGs offer something closer to literary complexity than do the almost exclusively killing-oriented FPS games, and, to some extent, this is certainly the case. Yet most RPGs stray far away from anything like novelistic action. Neither complex characterization nor plot is easy to provide in an RPG, since many aspects of these must be left up to relatively meaningless player actions (first turning right or left at a fork in the road, when eventually both sides must be traveled to complete a quest). The kinds of characterological arcs commonly found in traditional narrative seem beyond the grasp of RPGs, perhaps because the time investment itself in narrative character is incompatible with the fast-paced actions of RPGs. The user does not have time to watch characters develop the quirks and foibles, or experience the personal triumphs and tragedies, that are hallmarks of the interiorized novel. Plot elements emerge as overt and discrete: a character may interact with others for any number of reasons, but these are generally constrained within the economy of gameplay and no less within the several economies of accomplishment around which RPGs are structured. This is one reason why players of RPGs often evince little or no awareness of the game's putative plot.

Having talked with "kids these days", when I hear them intelligently loving a video game like Minecraft they aren't just being autists who like building castles in the sky out of materials they harvested and transmuted into building materials (and so on) but they think of "the real game" as the stories (that often more-than-half-scripted (sorta like professional wrestling)) between people who "play Minecraft" as performance art that is streamed to live audiences and posted on youtube and so on.

Kids these days have sometimes binged thousands of hours of this kind of stuff. Like if you look at the wiki page for "Dream SMP" the sections are "History & Plot", "Cultural Impact", and "Cast". It is more like a movie, or a mini-series, than like the sort of lonely work-like slog common to old MMORPGs where paying players farmed fake gold as a tragic displacement activity for a world where it is illegal for them to use their agency to get a real job, and mine real gold.

The actors play "video gamers who are playing Minecraft (for the love of the game)" with dramatic story lines (that makes numbers go up on social media (thus generating ad money)).

An interesting thing here is that play inside of seriousness (based on play (echoing seriousness))... is a common pattern. Like arguably, evolution is deadly serious, but also... it invented play?!? But arguably, evolved play is simply practice for real fighting? But also, new ways fighting inspires more play in kids who inventively copy the fighting that seems fun to copy. And so on. See again "professional wrestling".

A common way for these Minecraft SMPs to break down, from what I can tell from a distance, is for the actors to become embroiled in a sex scandal... which kinda checks out? Like in House Of Cards the evil protagonist would often do a villain monologue to the camera, and would paraphrase Oscar Wilde without attribution, saying "everything is about sex, except sex; sex is about power". Once the actors start trying to cash in their playfully displaced game fame into raw evolutionary fitness attempts on unsuspecting fans, they start losing fans, and other actors are then professionally required to shun them or else lose fans, and so on.

This is an interesting history that I think would be interesting to send back in time to "Golumbia in 2015".

Unfortunately Golumbia passed away recently and is sorely missed. He explicitly states in the story that a game "without play" was not intended as a "sick burn" of any kind, and that he himself enjoyed these games. As a sometimes Minecraft player, I can for sure see there are indeed many elements of work within the game, as well as some necessity to create order and preserve oneself by securing shelter and resources. The joke "the children yearn for the mines" is a direct reference to this same observation, and Golumbia's paper only shows this dynamic might be a good question to be concerned about. I don't quite see where you are going with this claim that his conclusions are outdated, other than making a side point about changes in game genre conventions over the past decade.

"Play" and "not play" are far from value judgments, but rather fairly intense loaded terms that came out of the application of Husserlian logic to fields like Anthropology, History, Linguistics, and so on in a movement called Structuralism:

If totalization no longer has any meaning, it is not because the infinity of a field cannot be

covered by a finite glance or a finite discourse, but because the nature of the field—that is,

language and a finite language—excludes totalization. This field is in fact that of freeplay, that is

to say, a field of infinite substitutions in the closure of a finite ensemble. This field permits these

infinite substitutions only because it is finite, that is to say, because instead of being an

inexhaustible field, as in the classical hypothesis, instead of being too large, there is something

missing from it: a center which arrests and founds the freeplay of substitutions.(Derrida, Structure, Sign, and Play)

So to take it back to the video game example, Minecraft is missing a strongly defined narrative where a JRPG has, to a much greater extent, a central narrative that binds the player into a story where there are few choices and a lot of work-like "grinding."

The temptation and danger of AI is its conceptualization as the center of a narrowing marketing gimmick of hucksters.

Calling it a "sick burn" was itself a bit of playfulness. Every time I re-read this I am sorry again to hear that we lost Golumbia 🕯️

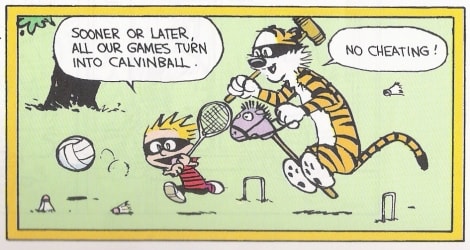

The thing I think is true about Minecraft is that it enables true play, more along the lines of Calvinball where the only stable rule is that you can't have any other rules be the same as before.

This is a good essay on what children's cultures have lost, and I think that Minecraft is one of the few places where children can autopoetically reconstruct such such culture(s).

Minecraft is missing a strongly defined narrative where a JRPG has, to a much greater extent, a central narrative that binds the player into a story

This is precisely the value of Minecraft I think, and why it is a cultural phenomenon. You can choose your own mods, you can make your own mods using open source tools, you can invent any story. Such, I suspect, is how real "play play" (with other people who will quit if it isn't fun) mostly works, and is related to why reading a novel isn't as fun as writing a novel with your friends.

I think it's still true that a lot of individual AI researchers are motivated by something approximating play (they call it "solving interesting problems"), even if the entity we call Anthropic is not. These researchers are in Anthropic and outside of it. This applies to all companies of course.

I interpreted the thrust of the essay as something else. But more broadly, I get why you'd find intuition pump essays manipulative, but not why you'd find them unconvincing.

The point is to take someone who says "I don't like any dish with onions", and give them a dish that has onions in it. They'd normally refuse to eat that, so you don't tell them, and then when they like it you can show them that their claim is wrong.

(I will note that I think "writing an essay with a surprising conclusion" is a significantly smaller violation than "feed someone food they explicitly asked not to be fed")

I think this essay is aimed at people who think things like "Better AI is always good, because it will do things better, and that's good." If those people were not saying "No, you should've kept making better bows until you put an arrow through your friend's chest" then maybe they don't actually think "better" is always good. (Basically the Orthogonality Thesis)

There's no need to strain a metaphor beyond its good use. The intuition pump as a surprise taste test could be more, a moral allegory as you've had it, but that's the very kind of narrative thread-weaving which I wanted to warn against.

What I want to emphasize most of all, and I'll be more direct and less clever now, is playfulness over minmaxing. Making and stockpiling increasing amounts of bows, ever more effective weapons, is not so much a metaphor for a game as it is the most immediate and serious existential threat to humanity, even moreso than the climate. If we're at all wise to the world, similar existential consequences from AI are still quite beyond the horizon. Serious to be sure, but these tenuous long strands of allegory, metaphor, and tapestries of analogy, the very substance of Rationalism and logic, are basically unfalsifiable and therefore closer to the mythological.

OP is onto something in pointing to playfulness, taking the way of Gandalf rather than Saruman. Saruman's way is precisely what Anthropic is doing, playing a defeatist game of ring-making, orc-breeding, and forest-burning.

As far as I remember, the optimal strategy was to

- Build walls from both sides

- These walls are not damaged by the current that much because it just flows in the middle

- Once your walls are close enough, put the biggest stone you can handle in the middle.

Not sure if that's helpful for the AI case though.

I love how this beautifully describes the spirit of play and challenge, as well as the phases of growing up and "not being able to play" anymore.

But I feel let down by the turn towards this being a metaphor for AI:

As a reader, I was drawn in by the ideas, imagery and writing, only to be led into what the author wants the metaphor to be about. The writing is excellent in itself before the switch, and the switch made that part merely instrumental for the twist. And while I don't know whether it was the case here, the idea that some authors at LW might feel that their beautiful ideas and writing need to be relevant to AI here makes me a bit sad.

I also think the metaphor is fundamentally wrong to the extent it indicates play and challenge as the main forces behind companies racing for A(G)I, whether you treat them as collectives of individuals or superagent entities. Similarly to any developed industry, I'm afraid the main forces behind the AI race are not the playful "we do it because we can" motivation or individuals rising to a challenge - this hasn't been true for a while now. By no means I mean to lessen the importance of personal responsibility or deny that excellent AI researchers work more efficiently with a good challenge, but think it is not a very good model for causality and overall dynamics here - for example I believe that if you removed the individual challenge and playfulness from the engineers and researchers (but keeping the prestige, career prospects, and other incentives), the industry would probably merely slow down a bit.

By the way, I was really intrigued by the parenting angle here - the idea of guiding my kids through how the game itself changes for them once they master it, and helping them mark their victories and achievements as a growing up ritual.

Curated. I think I like this post as a general reflection more than when it's tied back to AI (it's relevant to that, just, I like it as general reflection. It reminds me of Is Success the Enemy of Freedom? (Full) and opens up interesting questions of fun theory, questions of challenge and play as your capabilities grow either enough to be risky or simply that the challenges don't remain.

The point with Ai is interesting too. How much is human habit to keep pushing until something bad happens? In many domains, it's an easy extrapolation that something bad will happen (we don't want the river stopped or people hit with effective arrows), but AI while seeming obviously a serious threat to others has never been that bad yet, and so gets debated.

Can you explain more about the job helping the bank "win zero sum games against people who didn't necessarily deserve to lose"? Doesn't match my model of how investment banks work

Bostrom touches on a similar question of retaining the joy of striving in a 'solved world', in his recent book Deep Utopia. He points to sports as an existence proof that we can and do enjoy challenges (like your beach experiences) with artificial constraints.

Some of this feels like partly what is going on with modernity & apathy, at least among those of us priviledged enough to have abundant material comfort (which is not everyone).

The "collect playthings" game has been beyond won, is no longer fun, and we haven't collectively managed to choose our next game yet, for which we'd find ourselves in the more fun part of the curve.

This is an interesting analogy and a great essay overall, but I think that normies would benefit from an extra couple of sentences explaining the AI side of the analogy.

When I was a really small kid, one of my favorite activities was to try and dam up the creek in my backyard. I would carefully move rocks into high walls, pile up leaves, or try patching the holes with sand. The goal was just to see how high I could get the lake, knowing that if I plugged every hole, eventually the water would always rise and defeat my efforts. Beaver behaviour.

One day, I had the realization that there was a simpler approach. I could just go get a big 5 foot long shovel, and instead of intricately locking together rocks and leaves and sticks, I could collapse the sides of the riverbank down and really build a proper big dam. I went to ask my dad for the shovel to try this out, and he told me, very heavily paraphrasing, 'Congratulations. You've cracked the river damming puzzle. And unfortunately, this means you no longer can try as hard as you can to dam up the creek." The price of victory is that the space of games I could play was permanently smaller, and checkmate was not played on the board. This is what growing up looks like.

I experienced many variations. After I put a hole in the ceiling, building K'Nex catapults switched from a careless activity to a careful activity. On the more supervised side, when I was curious how big of an explosion I could make by taping together sparklers, I was not allowed to find the limit. After I cracked the trick of tillering, I could no longer try as hard as I could to build bows and arrows for the backyard battles my friends and I engaged in. I was and am particularly proud of earning this ban.

A couple years back, I got a job offer from an investment bank to help them win zero sum games against people who didn't necessarily deserve to lose. I had tried very hard to get that offer: leetcoding, studying build systems, crafting my resume. It was only once I got it that I realized I no longer could play the game "make as much money as I can." I had found the equivalent of smashing the river banks with a shovel and needed a new game.

There's an enormous amount of nuance here. If I find something that's sufficiently stronger than me, I can play hardball for a long time. My favorite game at the beach is playing in the outflow of a tidal pool at low tide. The river is pouring across the sand, but I, a child again, am stronger than river. My hands can dam it, make lakes, deltas, and canyons. The incoming tide is so vastly stronger than my hands that any consequences from me trying as hard as I can are erased.

Here still the ratchet of my understanding keeps closing off avenues. I could move past pushing sand with my hands or a shovel and start lobbying city council members to put in a groin or seawall, and seriously move that beach sand. And so I can't (and wouldn't really want to) actually try with my full effort. And even digging with my hands, I see the signs of innumerable coquina clams burrowing back down after every wave, signs that were invisible to a 4 year old, and I wonder: Can they really get back to the surface after being accidentally and swiftly buried in 2 feet of miniature civil engineering? I suspect that most of them can, and I continue.

This is, of course, about artificial intelligence development. Trying as hard as we can has been a fascinating and genuinely rewarding adventure. Personally, succeeding and blowing off my hand with the metaphorical sparkler bomb, would be less rewarding. This would be true even if I was a race with my neighbor to see who could blow off their hand first, or if, stretching anatomy and the metaphor, we all shared one hand.

On the positive side, Anthropic appears, in their latest report on usage in education, to be at least noticing the coquinas.