It is a common marketing maxim that “if you write for everybody, you write for nobody”. That is to say, you will write much more compelling copy if you have a clear target audience persona in mind. Lately, I’ve been musing on a concept that I think embodies the opposite of this – “explain to nobody, and you can explain to anybody”. I started thinking about this after I heard my husband and his techie colleagues mention “rubber ducking”.

I assumed I’d misheard, but no: rubber ducking is a technique that is commonly used by coders. The term originates, as with many tech terms, from a slightly ridiculous yet oddly effective idea. The premise is simple: when stuck on a problem, the programmer talks through their code line-by-line to a rubber duck. A small, yellow toy, sitting on the edge of the desk, unblinking, unjudgmental, maybe with head slightly cocked in listening mode. Talking through the problem out loud, having to progress through it in a logical way, helps the problem reveal and resolve itself. It’s a bit kooky, but it’s easy, low-tech, low-cost, requires no training — and is curiously powerful.

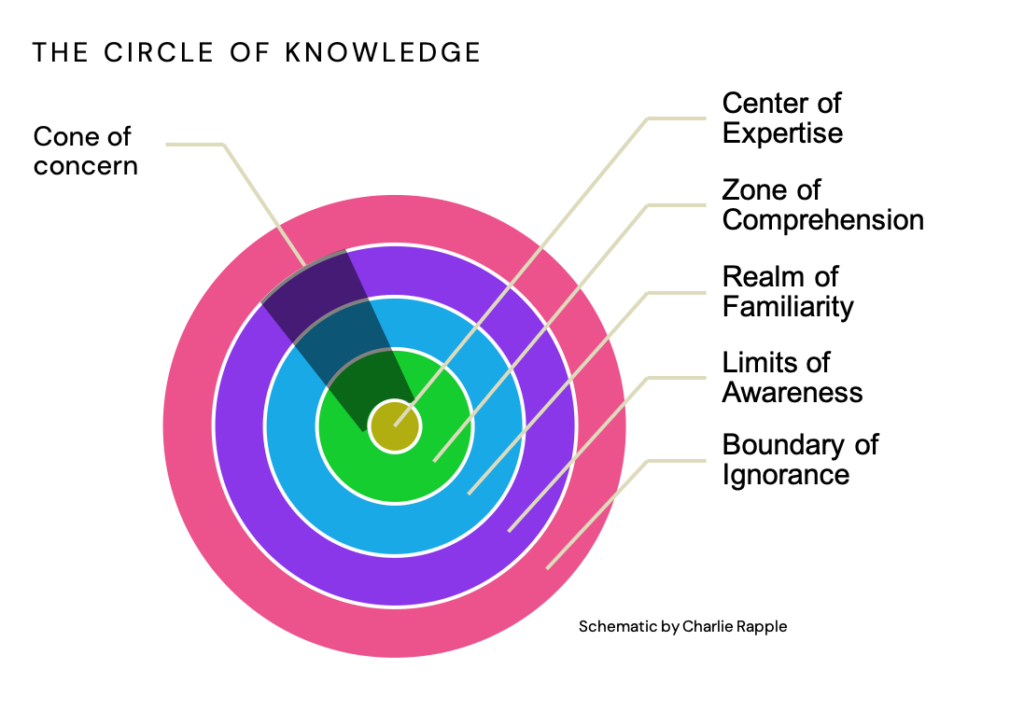

Anyone who’s read a published paper, or even just an abstract, knows where I’m going with this. Brilliant insights are often obscured by jargon, poor structure, or the confident omission of background knowledge (“of course, everyone knows how the modified ELISA was calibrated”). There are many reasons for this; sometimes it’s a deliberate attempt to obfuscate, sometimes it’s a lack of confidence, sometimes it’s about trying to make the research sound more impressive than it is. Most often, it’s just an assumption that our audience knows as much as we do, including the technical terms and ‘shorthand’. I’ve previously written about this and characterized it as a failure to adapt for the different levels in “the circle of knowledge”, in which concentric circles ripple outwards from the “center of expertise” through the “zone of comprehension” and the “realm of familiarity” to the “boundary of ignorance”.

But there can also be a more simple explanation: many people just don’t realize what they sound like when talking about their work. They’ve only ever talked about with people who nod along politely, or fill in the blanks. This is where the duck comes in: inanimate, unspeaking, making no effort to ease the conversation along. The act of explaining out loud to such a disengaged audience — duck, potted plant, voice memo app — forces a kind of mental translation. It slows you down just enough to notice when things don’t actually make sense, or when your explanation leaps from step A to step D before belatedly trying to roll back and cover steps B or C.

Rubber ducking is a mirror of sorts. It reflects gaps in logic, unjustified assumptions, and clumsy phrasing. It also surfaces what’s missing — those details so familiar to the expert that they’ve become invisible. To offer you a bit of cod-psychology (with apologies for bringing another aquatic species into the mix), there are echoes here of cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT). Describing your problem out loud means taking a step back from it, changing your perspective on it, taking a fresh look at what is actually happening rather than what your brain has got used to thinking is happening, and thereby finding a solution.

There’s something charmingly subversive about the duck, too. It breaks the intensity of scholarly performance. It invites playfulness.

I’ve read about companies that issue all employees with a duck as part of onboarding, video chat rubber ducks, terminal rubber ducks, and — of course — a ChatGPT rubber duck. For research communication, rubber ducking is an exercise in explanation that could be transformative. It’s often assumed that explaining research clearly is a public engagement thing but it has an equally important role within the academy. In a fast-moving world of shorter attention spans, increased competition for funding, and greater collaboration (more authors, more types of co-creators, more funders, more reviewers etc), clarity of communication is not just a nice-to-have add-on, it’s an essential tool for working more efficiently, effectively and successfully. I think there’s a role for rubber ducks in supporting more of a focus on communication, not just at the end of the research process, but as a habit developed throughout the research lifecycle.

There’s something charmingly subversive about the duck, too. It breaks the intensity of scholarly performance. It invites playfulness. It gives permission to be confused and then to un-confuse oneself. This is no small thing in an academic culture that prizes expertise and punishes hesitation. It just requires willingness: to speak out loud, to listen to oneself, and to catch the moment where something stops making sense — and to keep refining until it does.

Discussion

12 Thoughts on "Rubber Ducking For Research Communication: Why Explaining to Nobody Helps You Explain to Anybody"

I love this Charlie, the principle also reminds me of Up-Goer Five (https://splasho.com/upgoer5/), albeit perhaps a less restrictive version. Always a fan of speaking and writing plainly!

That’s pretty cool!

I LOVE Up-Goer Five! I once went to a British Ecological Society conference and they had asked all the poster authors to write a summary of their poster in Up-Goer Five. It was really inspiring, though hampered in some cases by the main focus of the research (e.g. a frog) not being one of the ten hundred most popular words!

Like your Circle of Knowledge diagram. However, I would suggest that your “Center of Expertise” circle be in two parts. First, an inner circle covering those who have both modern expertise and a full understanding of the history of their subject. Second, outside this, a circle for those with modern expertise alone. The latter may be acclaimed as “experts” because they know full well that the “peers” who may be reviewing their work are likely to be as unaware of the early work as they are themselves. For more on this please read “Scotoma: Forgetting and Neglect in Science,” a chapter in Oliver Sack’s The River of Consciousness”.

Oh what fun. This is new to me. reminds me of Jenna Hartel’s wodnerfully titled ‘Metatheoretical Snowmen’ See

http://www.jennahartel.info › metatheoretical-snowmen

She described this as ‘a thought experiment to explore the nature of metatheory in information science using the concept of a snowman’. In other words ‘interesting ideas Mr Derrida, can you please draw me a picture to show me what deconstruction would look like if it were a snowman?’ david !!!

Love this technique Charlie! It reminds me of the maxim if you can’t explain something simply – do you really understand it yourself?

Thank you. Great article and an important concept. Besides open access, science that can be understood, not just accessed, is critical. As Selma and Lois DeBakey, pioneers of the field of biomedical communication, once said, “ Nothing hinders communication as much as words, when they are used poorly or incorrectly.”.

I’ve been going through a whole professional development plan to learn more about bibliometrics – and I don’t think any one reading or seminar taught me as much as trying to explain a concept (Goodhart’s Law) to a neighbor who had invited me over for coffee.

I love that, Greta – great example!