Nov 24, 2007

It's a genuine pleasure to be here in New Zealand. I've traveled all the way from Stewart Island up to Northland and this is an astonishingly beautiful country. I come from Canada. I don't say stuff like that lightly because we're pretty proud of our beauty in Canada, but this is a place that is relentlessly beautiful. I took the bus from Auckland to Wellington a couple of days ago and people sort of looked at me like I was nuts. But – New Zealand has a desert. I never knew that.

And, you know, I jumped the tour and took the bus and discovered a desert and that's sort of like a metaphor for life or something. And the people here, I've told other people this, the people here in New Zealand are just lovely, lovely people. They have been kind and generous and they all say, or most of them I guess, I don't know about all, but they say, "Hiya." And for those of you who read my email, I always begin my email with, "Hiya." And I've never actually heard people say that. It was so neat. You know, I'm there and I walked into a café and, you know, the woman behind the counter, she goes, "Hiya." And I was like, "Oh, I'm home."

As the introduction said, I have been on the road a long time. I started in Frankfurt after an overnight flight from Toronto, after a flight from Moncton, and I was there for their Saturday morning market and I was eating Bratwursts. And then I found myself in South Africa and I went to Lesotho, which is that little round country that's completely enclosed by South Africa.

And I saw what they call cattle-boys and what cattle-boys are, they're people who tend to their herd of cattle and the herd of cattle is 12, 15 cows and they sit on their horse. They always have a horse or a mule and they have a stick and they wear their blanket and they wear their hat. They used to wear their traditional Basotho hats, but now most often they wear something like a toque. They all have these blankets and toques. It's Africa. And they always have one dog or two dogs. And that's what they do. They tend their cattle.

And I was talking to people there about, you know, because they start this life when they're five years old, six years old and they go off – they go into the mountains and they're on their own and they're tending their cattle and, they feed themselves and they clothe themselves and all of that. And the government and other agencies try to offer them schooling, but the schooling would bring them down from the mountain and they don't want to come down from the mountain.

And, you know, having seen their mountains, I don't blame them. I wouldn't want to come down from that mountain either. I wouldn't want to leave my horse or my mule and my dogs, especially not my dogs. I wouldn't want to go to a school and have to not wear my blanket anymore or my hat or whatever and it's just – so I'm sort of thinking, well, how do you educate them? How do you provide an education and what do you do to that sort of society when you're offering that education? What does that change?

And I was in Johannesburg, which is where I lost my passport and my airline tickets. And I'm told Johannesburg isn't the place to do that. And I went to Kruger National Park. This was while I still didn't have a passport and airline tickets. I figured, well, I'll go on safari if I can't go overseas. And I saw zebras and no lions. I didn't see lions or more accurately, they didn't see me.

And I saw Cape Town and I was briefly in Australia and then of course here, from Stewart Island, Christchurch and Dunedin, Auckland, Whangarei. So, I'm overwhelmed. And I'll admit that I'm standing here before you right now overwhelmed, overwhelmed with sensory experience, overwhelmed with cross-cultural experience. I was thinking just as I was skipping the coffee that I was having information overload. And for other people, information overload is 1,500 emails. I deal with that, you know, pretty much every day. For me, information overload was like real life. The irony struck me.

So what this talk is: a long time ago, I was asked to write an outline and I really didn't know what I was going to talk about because I knew I was going to go through all of this and so this talk is some of the reflections that come out of all of that and those reflections as applied to the sorts of things that I have to say about learning technology, learning networks, e-learning and all of that stuff. This trip has probably done lots of things to me which I won't discover until months later, but what this trip has done to me now is have me see my own thinking in a different way, from a different perspective and that's always a good thing.

So, here's the setup. What we're seeing the emergence of the personalized web, the interactive web, web 2.0, or e learning 2.0. And the question that faces us typically is how should the learning sector, how should we respond. And the short version of that is very badly so far. I've been struck by the oddity because I've gone from place to place, college to college, school to school and I find that most of the technologies that I'm talking about and I want to demonstrate and show people are blocked. And I find that a very odd sort of thing.

And now, after all of this, I'm thinking of it as walls. It's just walls all around me. I want to talk to someone. There's a wall. I want to do a blog post. There's a wall. Mostly, schools, colleges, universities have been reacting to these new technologies by blocking them. And I know there are good reasons for that and I know there's security and all of that, but you know, I mean security is like walls.

The best of walls around your house isn't gonna keep people out. You know, the best security system isn't gonna block people. I'm reminded of the Microsoft Darknet paper1, a very famous paper written by some Microsoft technicians, and they're writing about digital rights management and their conclusion essentially is that no digital rights management system will succeed. Any way of locking down content will inevitably be broken. And Microsoft should know.

You know, they come out with a security system and three days later the crack comes out for it. I mean, I read just this morning2 that Microsoft is suing the people who wrote software at the – what was it, a free WMV or something like that. It's software that cracks the security encryption on the Windows Media format. You can't build a society with walls.

I was at one of the technical universities in South Africa and they can have WiFi and have internet access and all of that, and of course, like all the other universities, they're locked down. You have to give you name, your address, your Mac address, your blood type, your mother's maiden name and then maybe, just maybe, they'll let you have it – and anyhow that system was hacked and so it was down while we were there.

In the longer term we have to do something more imaginative than blocking this technology. We need to live and teach and learn where the students live and teach and learn. That means that we have to stop blocking to their spaces and go to their spaces. So we explore their world. But, you know, there's the age-old danger of explorers that when we go to their world, we're going to want to colonize it. And we're going to want to make them like us. And we're going to want to take them from their mountains and put them in rooms and put walls around them and put locks on their doors and say, "This is civilization."

And that appears wrong to me and it appears wrong to me not just because I was recently in Africa. It has always appeared wrong to me. I mean, again, I'm from Canada. I'm most at home when I'm in a forest and there's nothing around me, there's no walls or no barriers. Maybe there's a river, but whatever. And so it just does seem wrong to me.

Now, how is this playing out? Dana Boyd wrote a brilliant paper on MySpace, Identity Production in a Networked Culture3, about the way people use MySpace. And basically what she says in her analysis of MySpace and in the group – in the workshop yesterday4 we actually went to MySpace and looked around at the sites. What she says is that MySpace is identity production playing itself out visibly. People creating and demonstrating their own identity in this online world. And I commented yesterday, 86 million people, they can do anything they want, they can express themselves and they come up with that? But that's MySpace.

We heard, especially in our traveling group here in New Zealand, we heard a lot about Second Life. Second Life to me is almost an old story and it's almost an old story because I actually came onto the internet sometime in the late 1980s as a participant or a player in what was called a ‘multi user dungeon', or MUD. And I, in particular, played on a MUD called MUD Dog MUD. "Virtual reality at its best. Based at the University of Florida." I can still remember the title screen in my head. My online character was Labatt the Cat and I was a wizard. Actually, I was a senior wizard. I was very proud of that – more proud of that than my BA. And Sherry Turkle, again, examines the world of MUDS.5 MUDS are like Second Life except without the graphics. Funny how you describe things – how that changes over time.

And again, and I saw this for myself, people playing in these MUDs are creating their own identity. They're trying on different hats. They're trying on different ways to live, different ways to interact and that's okay. I was going to say we don't say that this is good or this is bad, but of course we do say that this is good and this is bad. And then I wanted to say, "Well, we don't mean it." But of course we do mean it. But mostly what I want to say is this kind of diversity, including of opinion, is expected. A MUD is one of these wild free ranging places and that's also true of Second Life. Except with graphics.

All of this – you know, my background in MUDs and creating and recreating my own identity online and then I'm sure many of you have seen my own identity online in my web page and my other web page and the secret hidden webpage that nobody's allowed to see. It's not a very popular one.

And all of that, and my background, and then coming through New Zealand with the traveling group: all of that has put me in a position where I'm looking at the contrast (‘contrast' is the word I'll use right now) between groups and networks. And I posted in my website a few days ago6 that groups require unity and networks require diversity. Groups require coherence, networks require autonomy and so on.

And to put that into context right now historically. Those of you who've taken political science know that all of human history in political science is the division between the individual and the state. Right? The person and the group, right? And these are the two divides. And the whole purpose of politics is to find some sort of accommodation for them or if you're Ayn Rand, to favor the individual and ignore the group.

And it seems to me that networks offers that middle way. Networks offers that path that isn't the individual and isn't the group, doesn't force you to choose between the individual and the group. I am saying this because as soon as I came up with this "groups versus networks" people are looking at that and saying, "Well what's the middle way with that?" And I thought, "Wait a sec, this is the middle way.

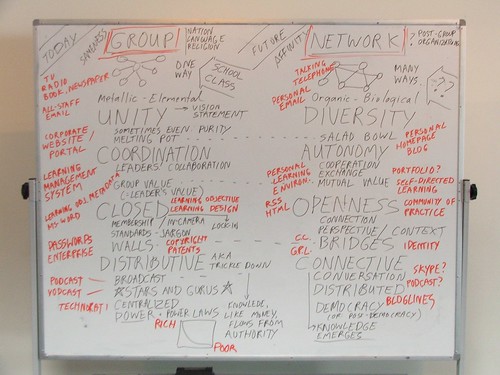

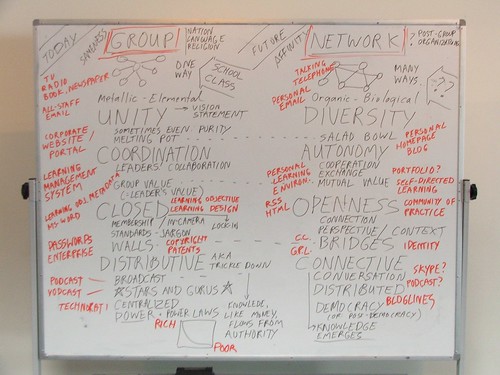

So I drew this picture:

I drew this in Auckland. Because I was talking like this and I wanted to draw out what I meant by that distinction between the group and the network. The rest of the talk is basically about this diagram.

Now if I was doing this diagram today instead of three or four days ago, it would be a bit different, but not a lot different because not a lot of time has passed. And these are not definitions. I don't do definitions. So I don't want somebody coming along like five years from now and saying, "Stephen Downes defines a network…" I'm just trying to give you some words to give you kind of a mental picture of what I think this is, and I won't be bound by these words.

But more or less, a group is a collection of entities or members according to their nature or their feature or their properties or whatever, their essential nature, maybe, their accidental nature, maybe, whatever, but according to their nature. What defines a group is the quality the members possess in common and then the number of members in that group. Groups are about nature, they're about quality, they're about mass. They're about number.

A network, by contrast, is an association – I use that word very precisely – an association of entities or members where this association is facilitated or created by a set of connections between those entities. And if you say, "Well what is a connection?" A connection is merely some conduit along which a signal can run. Well, that clarified it, didn't it? What defines a network is the nature and the extent of this connectivity. The nature and the extent to which these individuals are connected together. Now that may be perfectly fuzzy, but this is the overall view.

A group, in other words, is like a school, a school of thought or a school of fish or a class, a class of entity, a class of animals, a class in a genus and a species. A class act is kind of a group. Or to flip that around classes in schools, properly so called, the things that we all grew up in are groups because groups are classes in schools. And once that line of reason, I started looking at dictionary definitions and I started doing Google image searches on the word school. I bet I've never done that before.

And I'm asking can we even think of schools? Can we even think of classes without at the same time thinking about the attributes of groups? Can we separate in our head those two contexts or have they been irrevocably fused in our minds?

The discussion I've had since I've come up with this points more toward irrevocably fused, but I hope to shake that a little bit. So let's come back to the challenge, only rephrased with the date in Finnish (Stanley Frielick, kirjoitti 27.9.2006 kello 12:35) - because I wanted to include some Finnish in this presentation. "Education and authentic learning," he writes, "like freedom, is wrapped up with the notion of responsibility and accountability. We need to learn in groups because that's where we form our identities."7 True or false? "Not in some vast, chaotic network where there's no responsibility, no authenticity." Fascinating how responsibility and authenticity and all of these things are joined together.

That last little bit harkens to Hubert Dreyfus who is basically – I don't want to say anti-internet because that would radically oversimplify his position, but Dreyfus says, basically, there is no genuine effects, no genuine cause and effect, no genuine consequence to your actions on the internet.8 Now I grew up on MUDs. I know how false this is and the interactions that take place on the internet, contrary to Dreyfus, are real and as I said in the group yesterday, I read this somewhere, I forget where, ‘real' is defined as "the effect continues to linger after you've turned off the computer." If that happens, it was real.

A group is elemental. Remember, a group is defined according to its class and the number and if you want to draw a mental picture, draw a mental picture of one of those ingots of pure gold or something like that. And the idea here is that all of the elements in that ingot are the same. They're all gold atoms. Right? And they're just all lined up together and what makes it more or less valuable is how many of those atoms there are and how pure that ingot of metal is.

Interestingly, democracy is a group phenomenon. Democracy is a bunch of people who are relevantly the same, they all voted Tory and what matter is how many of them there were. So, you know, so many people vote Tory, so many people vote liberal and those two sets – those two groups, that's how the government is defined according to how people voted. A network is different from that. And a network is – and other people have said this, I'm certainly not the first person to say this - a network is like an ecosystem where there is no requirement that all the entities be the same, where the nature of the entity isn't specifically relevant, where the number of entities isn't specifically relevant.

(I once got a twenty out of ten, I was so proud, on a project. It was a bottle of water from the stream and it was tightly sealed and I called it "closed ecosystem project." And I reported on the slow death and decay of everything inside that bottle.)

So we hearken back to what Stanley said. We have a group or we don't and without the group, there's no responsibility, there's no order, there's nothing but chaos and mass anarchy. And the question is, can we have order, responsibility, identity, all of that good stuff, inside an ecosystem? Is the choice before us really order or anarchy? And I argue, no, that isn't the choice. I argue that not only can you have all of those good things inside an ecosystem, inside a network, but also that in many ways, they are relevantly better.

And, you know, it's funny – Solon was a Greek icon and is known, to say this briefly, known for bringing the concept of universal laws to Athens. If you think about how law is managed in the ancient societies, two people come before the king and they each plead their case and the king sort of goes, "Hmm, you. You win." And the problem is, for societies without laws, you do that enough times and then the king says, "Hmm, you're in my family. You win." And so that sort of problem was happening in Athens where justice was blatantly unfair and so what Solon did is he brought a system of laws that would apply for everybody. And so he brings the concept of universal law that applies equally and the same to everybody in Athens. And it's funny how that has survived as an essential and elemental concept in learning today.

I commented, and not purely in jest, when talking about assessment. I want to change the system of assessment in schools because right now we have tests and things like that that are scrupulously fair, particularly distance learning where we outline the objectives the performance metrics and the outcomes and all of that. I want to scrap that system. I want testing to be done by at random by comments from your peers and other people and strangers based on no criteria whatsoever and applied unequally and unfairly.

And people say, "Well, why would you want that?"

And I said, "Well, that's the way the world works."

But the point of that remark is to try to pull apart this idea of universality, everything being the same and learning. Do we need, as is suggested, do we need the iron hand of justice in our classrooms?

Groups – groups are defined by their unity. In fact, one of the first things you do in a group is you try to maintain its unity. A group need to be, in some sense, cohesive, united, "e pluribus unum". Or to keep this politically fair, "The people united will never be defeated," the "melting pot", the encouragement to be the same, the encouragement to have the same values, to follow the same vision, to be, in some relevant way, like the others because that's what the group is. Without that sameness, you don't have the group. You have anarchy.

And we have technologies specifically designed for the group, pre internet technologies appeal to the mass and you're familiar with these – mass broadcasts of television, of radio, newspapers, books. These are things that create the identity of the group and therefore, because the nature of the individual is the same as the nature of the group, it creates the identity of the group.

Think about, in your own country, have there been these moments that have defined the country captured on video and played over and over for your children? In Canada it was in 1972. We played a hockey series – Canada against the Soviet Union. They were evil. We won. It was great. Paul Henderson's goal, I can almost like hear and recite back the play by play announcer. I watched that game sitting in an open concept classroom in Metcalfe, Ontario, with about 50 other kids on one of those little TVs way up on the little rolling stand. And when Henderson scored that goal, we went nuts. And it defined our generation. Unity.

Online, we do pretty much the same thing. We have technologies that appeal to the mass and are used to create unity. All-staff emails – how many of you got an all staff emails? I was talking with Brandy before this talk, she got an all staff text message. An instant message sent to everybody in the ‘buddy list', 200 people or whatever got the URL for the corporate website, the portal. These are "all" things, out of many, one. Out of all these staff and employees in your company or your university or whatever we're gonna have this website and this website will speak for all of us.

Networks are almost defined by the opposite, defined by their diversity. A network thrives on diversity. It wouldn't be a network without diversity. To each his own, so goes the saying, and I know it's not gender neutral, but it's a very old saying so I was faced with a choice. Do I quote the quote accurately or do I put it gender neutral? So I thought I'd quote the quote accurately and then apologize for 30 seconds.

Interestingly, when I grew up, and again I grew up in Metcalfe, Ontario, small farm town south of Ottawa, population 500, we were feral. We roamed the fields and the forests and if there were deer we would have chased deer, but there were cows, so we chased cows. And our teachers would teach to us that Canada was different from the United States. And much later on, I realized, oh, that is Canadian identity.

And the United States, like groups, constitutes a melting pot. In Canada, we were all taught, is a salad bowl where each entity, the lettuce, the tomato, the whatever, cucumber, I don't know what you put in salads. That's what we put in salads. All of these things maintain their distinctness and their identity and by maintaining their distinctness and identity, they create a whole that is something distinct and different from any individual entity and indeed, something that cannot be created without maintaining that distinctness and identity.

And the more I thought about this, you know, I struggle with myself all the time and I wonder, was it indoctrination or were they right? And after many years, I've come to the conclusion they were right.9 And so there is this idea of the network, there is this idea of distinctness and diversity in an environment where people are encouraged not to be the same, but to be different. I like to think I have fulfilled my teacher's expectation, having internalized the encouragement not to consume and to absorb the message from the mass media, but to create, to be that media, to be the artist, to be the writer, to be the videographer. Canada routinely wins awards for its documentaries. We are the nation of documentary makers. I even made a documentary recently.10 Why? Because well, I'm Canadian. I had to. It's in the contract.

Network technology that includes diversity, encourages diversity, talking – talking is wonderful and talking is not a mass phenomenon – telephoning, writing letters, personal emails, do you see what characterizes these things? Right? They're not one to many, they're one to one, and sometimes in the internet age, they're also many to many.

But the idea here is that what defines these things is the set of connections between the individuals and not the content of what's going out. If you try to define what you mean by, say, telephoning or letter writing by the content of the messages, how would you do that? They're not even all in language, especially not with sending pictures and things like that.

Internet technology that encourages diversity rather than conformity includes things like personal home pages or these days, blogs. I should add to this slide MySpace profiles and things like that, your account on Flickr. All of these things that allows the individual to express themselves rather than the individual being part of some larger entity. It's funny, I have an email address, surprise. My email address is stephen@downes.ca.

And I'm just curious now, almost all of you will have email addresses. For all of you, how many of you have an email address based on your institution, college, universities or whatever address? In other words, you know, fred@somepolytechnic.edu or whatever? Where is your personal identity? Why the email? This is your email address. And yet your email address is your institutional address. How did that come to be? Imagine if your personal mail address, the mail that you get from your grandmother, came through your employer and had to be sent to your employer before it got to you. It just seems odd.

Groups require coordination. They require a leadership or a leader which is why we get all of this stuff on leadership. It's the funniest thing, all these things on leadership, because I read these and it's like everybody needs to be a leader, but my experience of groups is usually one leader and a bunch of followers and, you know, I want to see the new business book that says, "Everyone should be a follower." But no. I always look at these things from the point of view of the follower.

People think about groups and leadership and direction and responsibility and they usually mean "my leadership, my direction, responsibility to me." And I look at groups differently because they don't let me lead groups. I look at groups as somebody else's leadership, somebody else I'm responsible to. I have to follow his or her vision, as being "responsible" assumes that I'm under somebody. People picture groups, but they don't picture them in terms of their actual role in the group. They picture them in terms of the role they would like to play in the group. It's a philosophy of aspiration rather than a philosophy of reality.

This is something that socialists need to look at because socialists appeal to groups. They appeal to the worker, but nobody wants to be a worker. That's why socialists, at least in my country, get like 16, 20 percent of the vote. You know? I'm surprised 16, 20 percent of the people identify, "Yeah, I'm a worker." But, you know, people don't want to be a worker. They want to be a manager or retired, one or the other. Socialists speak to neither of those.

A group is defined by its values. I said yesterday and I say it again today, the person who came up with the concept of the vision statement should be thrown out the window. Because think about it. You're in some institution. The powers that be from on high come down with a vision statement. You read the vision statement. How many of you go, "Yeah, that's my purpose in life?" And what follows is a long, protracted exercise to get you to replace whatever vision you had with the vision of the group. And it seems odd. Groups define standards. Groups define belonging.

In learning technology – most of learning technology is intended to support this picture – we have the learning management system. Managing learning. If you think about that, think about what that says to manage learning. What does that mean? It means there'll be a manager of learning. It means that there'll be one person responsible for the learning and everybody else will follow. Learning design, where the learning is organized, sliced, diced, flaked and formed and you follow in a row or you're not a learner. You're an anarchist. Learning object metadata, the 87 or whatever fields to describe a learning object, a learning object being something that can be assembled like a Lego, like individual entities in a group, and this is the one and only way to describe learning resources. And if it's not a learning object metadata, it doesn't exist.

Networks, by contrast, require autonomy. That is to say each individual in a network operates independently. That does not mean they operate alone. What that does mean is – because remember, it's a network, you're connected, you talk to people, they talk to you – it means you define your vision. It means you define what's going to be important to you, your values and interests. It means that when you go to work, the reason why you're at work is because you want to put food on your table, not the boss's table. The boss getting food on his or her table, that's just an accident. But that's not why you're there.

Interaction in a network isn't about leaders and followers. It's about, as I say here, a mutual exchange of value. And my employers don't like me that much because that's how I view myself as an employee. And I go into there and they say, "Well, we're gonna give you these orders now."

And I sort of say, "Well, what are you going to give me for doing that?"

And they say, "Well, we pay you."

I say, "Well you paid me before. You know, we already had an agreement and now you're changing the agreement and that's fine. You can change the agreement, but now I want some changes too." Because it doesn't work that way if this is a mutual exchange of value. You can't just change the condition. I hear so many people say all the time, it was even in my email this morning, it was stuff about networks and that and people say, "Oh, but we're in this institutional environment. We have to do what we're told."

And my response is, "Who said so?" I mean, why? I mean the worst thing they could do is fire you and then you'd be free, but if you belong to a union (another group, right?) you can actually set one group against the other and not follow their orders and still manage to be able to eat and house yourself.

And it's a fascinating – when you reframe these things – you need to reframe these things. Think about the arrangement that they have set up for you. You will do what they say or you will be forced to be homeless and starve. What kind of bargain is that? Right? So this objection is, "we have to do what we do or they won't pay us." But the only people who can change that arrangement is you. Your bosses aren't going to change it. Trust me.

People don't follow, they don't do what they're told in a network. They interact. They make their own decisions, but not completely independently all on their own, not all by their lonesome. They interact with other people. But they make their own decisions.

It's like traveling from Auckland to Wellington. Right? There's different ways you can do it. I mean you can travel with a tour group or you can take the bus. Right? Taking the bus doesn't mean that you're traveling alone. It just means you're not traveling with the group, but you still interact. But your interaction is different. Now it's in a mutual exchange between you and the bus driver or you and the bus company. And I give them money and they said, "Yes we will take you to Wellington and we won't leave you in the desert." And I said, "Good, because it's a nice desert, but I don't want to be left there."

And you think about the technology now that encourages autonomy rather than conformance. E-portfolios is being touted as this sort of technology. The same with the personal learning environments (and you might not know what that is yet because they're new, but if you look that up on Google, you'll find stuff on personal learning environments) and that's the autonomous answer, the network answer to the learning management system. And it's based on a radical concept. Students can learn autonomously. Who would have believed?

But if you read and listen to all this pedagogical theory, it's like, "gee, if we don't take them by the hand and lead them through this, they'll be hopelessly lost and they'll never learn anything at all."11 And if that were true, the internet never would have been built. There were no classes on how to build an internet before it was built. How did they learn? Well, they learned on their own, self-directed.

Groups are closed. This is the ‘walls' part of it. They require a boundary that clearly defines the distinction between members and non-members, otherwise there wouldn't be a group. They would not even a mob, because a mob at least has a border. Groups have memberships. Membership has its privileges. They have logins and passwords and authentication and blood type passes. They have control of vocabularies and standards, jargon. They have in-jokes. You will use this technology. I'm a Mac person. I'm a PC person. Staying on message, he's a loose cannon, he's not part of the group. We speak as one. With one voice we speak. That's what a group is.

A group defines itself with very precise limits. Look at the limits. Look at the boundaries. Look at the walls that you have in your learning environment today, your learning technology environment, even your learning environment today. Look at the walls here right. We've managed to keep all the other people out. Right? And if somebody who was just walking on the street tried to come in here, sit down and listen, we would stop them. Think about that. That's our theory of learning. If somebody wants to come in and listen, we stop them.

Enterprise computing, federated search, federated search is a system whereby you search only accepted resources, resources that have been approved, qualified and typically are commercial and for sale. User IDs and passwords, copyrights, patents, you cannot use that shade of green it's owned by BP. You cannot use the word Coca Cola, not even to talk about Coca Cola because we own that. I can say ‘elearning 2,0' I invented the concept web 2.0. You can have a conference, but you cannot call it web 2.0. I'm blackboard, I invented the learning management system. We will put a wall around anyone else trying to do it.

And even whether or not it's true or not true, it doesn't matter. You build the wall and it becomes true. Assertions of exclusivity define groups. Networks are the opposite of that. Networks are open. Networks require that all entities in the network be able to both send and receive. To send and receive, first of all, in their own way, because they're diverse, and secondly, without being impeded. Well, oddly, that is a radical concept.

It's hard to believe that something like freedom of speech is a radical concept, but there it is. In their own ways, a person in a network should be able to send their message any way they want in their own language using their own computer encoding, using their Macintosh computers, using standards that are non-standards. I talk from time to time about RSS. RSS – sometimes people talk about RSS in the same breath they talk about learning object metadata ‘cause they're both types of XML, but if you look at the history of RSS, it's a mess. There is not such thing as RSS or no individual thing as RSS. There's eight or nine or ten or we don't even know how many different types of RSS and some types of RSS aren't even called RSS. And yet it works. There are many, many hundreds of times more RSS feeds that there are learning object metadata feeds. In fact, I don't know if there are any learning object metadata feeds.

In networks we have communities of practices where a ‘community' is defined as collections of individuals that exchange messages and ideas back and forth without being impeded. Copyright, trademarks, proprietary software, all of these things are barriers for the communication of thought and ideas. If you allow that using content, images, text, video is a way of speaking to each other, then copyright, trademark, all these things are ways of locking down our speech, saying, "I own the word such and such and you can't use it."

Imagine I invented radar and I decided I am going to own the word radar from now on and anybody who talks about radar has to get my approval before they can use that word. Can you imagine how communication works in an environment where you have to get permission in order to use a word as simple as radar? But that's what's happening now with all of this copyright stuff. The network approach to this stuff is to open this up, create a license for works and content like GPL.

The network response to a meeting like this with four walls, a ceiling and happily a floor is this, the iRiver, in this case, which is recording this talk in MP3 After this talk, sometime, I'm going to do a radical act. I'm going to take the talk that I just gave and I'm going to put it on the internet and anyone can listen to it. And they won't even have to pay me. And even better, they can take this talk, they can put it on their own computer system, they can print it out on a CD and pass it around their village or farm or whatever.

They won't have to pay and if they think I've gone on too long (a lot of people think that) they can chop it up and just do little snippets, like, "A lot of people think that." And, you know, you hit a button, "A lot of people think that." And they can mix and mash and I want them to do this because I want part of my words, my thoughts, my thinking, my ideas to become part of the culture, part of the language, part of the dialogue. And it strikes me as – and the only way to do that is to no longer own it. The only way a word becomes a word is if you let go of it.

Groups are distributive – money, information, power, everything flows from the center, an authority, and it's distributed through the members.

Networks are distributed. In a network, there is no locus of knowledge. There is no place that knowledge and money and all of that flow from. Rather, the knowledge, the money, the information, anything that is exchanged in a network is distributed across the entities of a network. When an idea propagates to a network, it does not come from a centralized source, rather it comes from any given source in the network and then through a process of what they call propagation, it works its way through the network.

Think about diseases (yes, I came here and talked about diseases). You know, there's no central disease authority where we get all of our diseases from, happily. Some say the CIA, but that would be the group way of doing it. Diseases spring up anywhere. The flu comes from Hong Kong, Ebola comes from Ebola, you know, they can spring up anywhere and then what happens is they propagate person to person, contact to contact and there's a very specific logic of how diseases propagate from person to person, contact to contact and it's this whole social networking graph theory.

And the mathematics of that is actually very simple. If the probability that the disease will be passed on is greater than one, the disease will spread through the society. If the probability is less than one, it will be halted at some point. And then you work around the mechanics of all of that. So the network works that way. The network works where the idea, the money, the resources, whatever, may happen to be anywhere and then it propagates link by link through the entire network and then each entity working on its own will have a specific probability of passing this on. And if collectively the probabilities are, on average, greater than one, then the idea or the concept will become common throughout the network and not otherwise. And in practice, what you'll find is some parts of the network are such that the idea has been accepted there, but for one reason or another, it didn't quite make it to the rest of the network. And so you get variety within the network itself.

There's been a lot of talk, and this is sort of just in the back of my mind while I was saying that last sentence, which is why that last sentence was a little confused. There's a lot of talk these days about something called a power law in networks and what a power law is a way of explaining the distribution of links in a network and it looks like this. So there's sort of a curve. Right?

And the idea is that some sites, like Google, have many, many links, links in from other people. Lots of people link to Google. And then you've got other sites like my site, you know, a few thousand people and then other sites, a dozen people and then many, many, many other sites, you know, just two or three people. So you have what they call that the ‘long tail'. This is where the new economy is and all of that. It's the long tail and all of these individuals of just two or three links, but the thing is, you know, this message is being given to us mostly by people who are in what I call the big spike, the A-listers. And they're sitting there saying, "Look at this power law. We're out here. We're making a mint."

But the thing is, that power law of distribution is more characteristic of groups than it is of networks. A network, properly constructed, will not see that configuration where two percent of all the people own 80 percent of all the wealth. Rather, it becomes more distributed – the more evenly you distribute your links, the more evenly you distribute your wealth.

Why networks? Three major reasons.

First of all, the nature of the knower. Human beings resemble ecosystems more than they resemble lumps of metal.

Secondly and very importantly, the quality of the knowledge. Because the knowledge comes from the authority, from the center, even if there's consultation and all of that, the knowledge of groups is limited by the capacity of the leader to know things. This is why dictatorships are so bad; dictators, as smart as they are (and some of them are very smart) just simply aren't capable of running an entire country by themselves. Nobody can do it. It takes too much memory, too much perception.

And then finally, the nature of the knowledge itself – the knowledge in a group replicates the knowledge in the individuals and it's passed on simple in a transmission communication kind of way.

Those of you who are into learning theory think more about transaction theory, of communication theory. It goes from here to here to here to here. And consequently, that limits the type of knowledge that can be created and communicated. I characterized it here a bit badly as simple cause and effect, yes-no sorts of things. The sort of knowledge you can get looking at mass phenomena. The knowledge you can get by polls and things like that.

But in a network, the knowledge is emergent. The knowledge is not in any given individual, but it's a property of the network as a whole. Consequently, it's a knowledge that cannot, does not, exist in any individual, but only in the network as a whole. It's emergent. It's more complex in the sense that it is able to capture and describe phenomena that are not simple like cause and effect, but complex like the nature of societies or the nature of the weather. That's a very loose characterization about it.

Thank you for your time. I really appreciate the invitation. I thank you so much for the opportunity to be here to speak to you. It's been a tremendous honor.

Notes

[1] Peter Biddle, Paul England, Marcus Peinado, and Bryan Willman. 2006. The Darknet and the Future of Content Distribution. Microsoft Corporation. 2002 ACM Workshop on Digital Rights Management.

[2] Fulton, Scott. 2006. Microsoft Sues FairUse4WM Developers. Beta News, September 27, 2006.

[3] boyd, danah. 2006. Identity Production in a Networked Culture: Why Youth Heart MySpace. American Association for the Advancement of Science, St. Louis, MO. February 19.

[4] Downes, Stephen. 2006. Online World. eFest, September 27, 2006.

[5] Turkle, Sherry. 1997. Life on the Screen: Identity in the Age of the Internet. Simon & Schuster (September 4, 1997).

[6] Downes, Stephen. 2006a. Groups and Networks. September 25, 2006.

[7] Frielick, Stanley. 2006. FLNW:: Re: Networking groups in the diverse world. The Future of Learning in a Networked World, Google Groups, September 27, 2006.

[8] Downes, Stephen. 2002. Education and Embodiment. April 26, 2002.

[9] Downes, Stephen. 2003. My Canada. July 1, 2003.

[10] Downes, Stephen. 2006c. Bogota. September 15, 2006.

[11] Kirschner, P.A., Sweller, J. & Clark, R.E. (2006). Why minimal guidance during instruction does not work: An analysis of the failure of constructivist, discovery, problem-based, experiential, and inquiry based teaching. Educational Psychologist, 41, 75-86.

And, you know, I jumped the tour and took the bus and discovered a desert and that's sort of like a metaphor for life or something. And the people here, I've told other people this, the people here in New Zealand are just lovely, lovely people. They have been kind and generous and they all say, or most of them I guess, I don't know about all, but they say, "Hiya." And for those of you who read my email, I always begin my email with, "Hiya." And I've never actually heard people say that. It was so neat. You know, I'm there and I walked into a café and, you know, the woman behind the counter, she goes, "Hiya." And I was like, "Oh, I'm home."

As the introduction said, I have been on the road a long time. I started in Frankfurt after an overnight flight from Toronto, after a flight from Moncton, and I was there for their Saturday morning market and I was eating Bratwursts. And then I found myself in South Africa and I went to Lesotho, which is that little round country that's completely enclosed by South Africa.

And I saw what they call cattle-boys and what cattle-boys are, they're people who tend to their herd of cattle and the herd of cattle is 12, 15 cows and they sit on their horse. They always have a horse or a mule and they have a stick and they wear their blanket and they wear their hat. They used to wear their traditional Basotho hats, but now most often they wear something like a toque. They all have these blankets and toques. It's Africa. And they always have one dog or two dogs. And that's what they do. They tend their cattle.

And I was talking to people there about, you know, because they start this life when they're five years old, six years old and they go off – they go into the mountains and they're on their own and they're tending their cattle and, they feed themselves and they clothe themselves and all of that. And the government and other agencies try to offer them schooling, but the schooling would bring them down from the mountain and they don't want to come down from the mountain.

And, you know, having seen their mountains, I don't blame them. I wouldn't want to come down from that mountain either. I wouldn't want to leave my horse or my mule and my dogs, especially not my dogs. I wouldn't want to go to a school and have to not wear my blanket anymore or my hat or whatever and it's just – so I'm sort of thinking, well, how do you educate them? How do you provide an education and what do you do to that sort of society when you're offering that education? What does that change?

And I was in Johannesburg, which is where I lost my passport and my airline tickets. And I'm told Johannesburg isn't the place to do that. And I went to Kruger National Park. This was while I still didn't have a passport and airline tickets. I figured, well, I'll go on safari if I can't go overseas. And I saw zebras and no lions. I didn't see lions or more accurately, they didn't see me.

And I saw Cape Town and I was briefly in Australia and then of course here, from Stewart Island, Christchurch and Dunedin, Auckland, Whangarei. So, I'm overwhelmed. And I'll admit that I'm standing here before you right now overwhelmed, overwhelmed with sensory experience, overwhelmed with cross-cultural experience. I was thinking just as I was skipping the coffee that I was having information overload. And for other people, information overload is 1,500 emails. I deal with that, you know, pretty much every day. For me, information overload was like real life. The irony struck me.

So what this talk is: a long time ago, I was asked to write an outline and I really didn't know what I was going to talk about because I knew I was going to go through all of this and so this talk is some of the reflections that come out of all of that and those reflections as applied to the sorts of things that I have to say about learning technology, learning networks, e-learning and all of that stuff. This trip has probably done lots of things to me which I won't discover until months later, but what this trip has done to me now is have me see my own thinking in a different way, from a different perspective and that's always a good thing.

So, here's the setup. What we're seeing the emergence of the personalized web, the interactive web, web 2.0, or e learning 2.0. And the question that faces us typically is how should the learning sector, how should we respond. And the short version of that is very badly so far. I've been struck by the oddity because I've gone from place to place, college to college, school to school and I find that most of the technologies that I'm talking about and I want to demonstrate and show people are blocked. And I find that a very odd sort of thing.

And now, after all of this, I'm thinking of it as walls. It's just walls all around me. I want to talk to someone. There's a wall. I want to do a blog post. There's a wall. Mostly, schools, colleges, universities have been reacting to these new technologies by blocking them. And I know there are good reasons for that and I know there's security and all of that, but you know, I mean security is like walls.

The best of walls around your house isn't gonna keep people out. You know, the best security system isn't gonna block people. I'm reminded of the Microsoft Darknet paper1, a very famous paper written by some Microsoft technicians, and they're writing about digital rights management and their conclusion essentially is that no digital rights management system will succeed. Any way of locking down content will inevitably be broken. And Microsoft should know.

You know, they come out with a security system and three days later the crack comes out for it. I mean, I read just this morning2 that Microsoft is suing the people who wrote software at the – what was it, a free WMV or something like that. It's software that cracks the security encryption on the Windows Media format. You can't build a society with walls.

I was at one of the technical universities in South Africa and they can have WiFi and have internet access and all of that, and of course, like all the other universities, they're locked down. You have to give you name, your address, your Mac address, your blood type, your mother's maiden name and then maybe, just maybe, they'll let you have it – and anyhow that system was hacked and so it was down while we were there.

In the longer term we have to do something more imaginative than blocking this technology. We need to live and teach and learn where the students live and teach and learn. That means that we have to stop blocking to their spaces and go to their spaces. So we explore their world. But, you know, there's the age-old danger of explorers that when we go to their world, we're going to want to colonize it. And we're going to want to make them like us. And we're going to want to take them from their mountains and put them in rooms and put walls around them and put locks on their doors and say, "This is civilization."

And that appears wrong to me and it appears wrong to me not just because I was recently in Africa. It has always appeared wrong to me. I mean, again, I'm from Canada. I'm most at home when I'm in a forest and there's nothing around me, there's no walls or no barriers. Maybe there's a river, but whatever. And so it just does seem wrong to me.

Now, how is this playing out? Dana Boyd wrote a brilliant paper on MySpace, Identity Production in a Networked Culture3, about the way people use MySpace. And basically what she says in her analysis of MySpace and in the group – in the workshop yesterday4 we actually went to MySpace and looked around at the sites. What she says is that MySpace is identity production playing itself out visibly. People creating and demonstrating their own identity in this online world. And I commented yesterday, 86 million people, they can do anything they want, they can express themselves and they come up with that? But that's MySpace.

We heard, especially in our traveling group here in New Zealand, we heard a lot about Second Life. Second Life to me is almost an old story and it's almost an old story because I actually came onto the internet sometime in the late 1980s as a participant or a player in what was called a ‘multi user dungeon', or MUD. And I, in particular, played on a MUD called MUD Dog MUD. "Virtual reality at its best. Based at the University of Florida." I can still remember the title screen in my head. My online character was Labatt the Cat and I was a wizard. Actually, I was a senior wizard. I was very proud of that – more proud of that than my BA. And Sherry Turkle, again, examines the world of MUDS.5 MUDS are like Second Life except without the graphics. Funny how you describe things – how that changes over time.

And again, and I saw this for myself, people playing in these MUDs are creating their own identity. They're trying on different hats. They're trying on different ways to live, different ways to interact and that's okay. I was going to say we don't say that this is good or this is bad, but of course we do say that this is good and this is bad. And then I wanted to say, "Well, we don't mean it." But of course we do mean it. But mostly what I want to say is this kind of diversity, including of opinion, is expected. A MUD is one of these wild free ranging places and that's also true of Second Life. Except with graphics.

All of this – you know, my background in MUDs and creating and recreating my own identity online and then I'm sure many of you have seen my own identity online in my web page and my other web page and the secret hidden webpage that nobody's allowed to see. It's not a very popular one.

And all of that, and my background, and then coming through New Zealand with the traveling group: all of that has put me in a position where I'm looking at the contrast (‘contrast' is the word I'll use right now) between groups and networks. And I posted in my website a few days ago6 that groups require unity and networks require diversity. Groups require coherence, networks require autonomy and so on.

And to put that into context right now historically. Those of you who've taken political science know that all of human history in political science is the division between the individual and the state. Right? The person and the group, right? And these are the two divides. And the whole purpose of politics is to find some sort of accommodation for them or if you're Ayn Rand, to favor the individual and ignore the group.

And it seems to me that networks offers that middle way. Networks offers that path that isn't the individual and isn't the group, doesn't force you to choose between the individual and the group. I am saying this because as soon as I came up with this "groups versus networks" people are looking at that and saying, "Well what's the middle way with that?" And I thought, "Wait a sec, this is the middle way.

So I drew this picture:

I drew this in Auckland. Because I was talking like this and I wanted to draw out what I meant by that distinction between the group and the network. The rest of the talk is basically about this diagram.

Now if I was doing this diagram today instead of three or four days ago, it would be a bit different, but not a lot different because not a lot of time has passed. And these are not definitions. I don't do definitions. So I don't want somebody coming along like five years from now and saying, "Stephen Downes defines a network…" I'm just trying to give you some words to give you kind of a mental picture of what I think this is, and I won't be bound by these words.

But more or less, a group is a collection of entities or members according to their nature or their feature or their properties or whatever, their essential nature, maybe, their accidental nature, maybe, whatever, but according to their nature. What defines a group is the quality the members possess in common and then the number of members in that group. Groups are about nature, they're about quality, they're about mass. They're about number.

A network, by contrast, is an association – I use that word very precisely – an association of entities or members where this association is facilitated or created by a set of connections between those entities. And if you say, "Well what is a connection?" A connection is merely some conduit along which a signal can run. Well, that clarified it, didn't it? What defines a network is the nature and the extent of this connectivity. The nature and the extent to which these individuals are connected together. Now that may be perfectly fuzzy, but this is the overall view.

A group, in other words, is like a school, a school of thought or a school of fish or a class, a class of entity, a class of animals, a class in a genus and a species. A class act is kind of a group. Or to flip that around classes in schools, properly so called, the things that we all grew up in are groups because groups are classes in schools. And once that line of reason, I started looking at dictionary definitions and I started doing Google image searches on the word school. I bet I've never done that before.

And I'm asking can we even think of schools? Can we even think of classes without at the same time thinking about the attributes of groups? Can we separate in our head those two contexts or have they been irrevocably fused in our minds?

The discussion I've had since I've come up with this points more toward irrevocably fused, but I hope to shake that a little bit. So let's come back to the challenge, only rephrased with the date in Finnish (Stanley Frielick, kirjoitti 27.9.2006 kello 12:35) - because I wanted to include some Finnish in this presentation. "Education and authentic learning," he writes, "like freedom, is wrapped up with the notion of responsibility and accountability. We need to learn in groups because that's where we form our identities."7 True or false? "Not in some vast, chaotic network where there's no responsibility, no authenticity." Fascinating how responsibility and authenticity and all of these things are joined together.

That last little bit harkens to Hubert Dreyfus who is basically – I don't want to say anti-internet because that would radically oversimplify his position, but Dreyfus says, basically, there is no genuine effects, no genuine cause and effect, no genuine consequence to your actions on the internet.8 Now I grew up on MUDs. I know how false this is and the interactions that take place on the internet, contrary to Dreyfus, are real and as I said in the group yesterday, I read this somewhere, I forget where, ‘real' is defined as "the effect continues to linger after you've turned off the computer." If that happens, it was real.

A group is elemental. Remember, a group is defined according to its class and the number and if you want to draw a mental picture, draw a mental picture of one of those ingots of pure gold or something like that. And the idea here is that all of the elements in that ingot are the same. They're all gold atoms. Right? And they're just all lined up together and what makes it more or less valuable is how many of those atoms there are and how pure that ingot of metal is.

Interestingly, democracy is a group phenomenon. Democracy is a bunch of people who are relevantly the same, they all voted Tory and what matter is how many of them there were. So, you know, so many people vote Tory, so many people vote liberal and those two sets – those two groups, that's how the government is defined according to how people voted. A network is different from that. And a network is – and other people have said this, I'm certainly not the first person to say this - a network is like an ecosystem where there is no requirement that all the entities be the same, where the nature of the entity isn't specifically relevant, where the number of entities isn't specifically relevant.

(I once got a twenty out of ten, I was so proud, on a project. It was a bottle of water from the stream and it was tightly sealed and I called it "closed ecosystem project." And I reported on the slow death and decay of everything inside that bottle.)

So we hearken back to what Stanley said. We have a group or we don't and without the group, there's no responsibility, there's no order, there's nothing but chaos and mass anarchy. And the question is, can we have order, responsibility, identity, all of that good stuff, inside an ecosystem? Is the choice before us really order or anarchy? And I argue, no, that isn't the choice. I argue that not only can you have all of those good things inside an ecosystem, inside a network, but also that in many ways, they are relevantly better.

And, you know, it's funny – Solon was a Greek icon and is known, to say this briefly, known for bringing the concept of universal laws to Athens. If you think about how law is managed in the ancient societies, two people come before the king and they each plead their case and the king sort of goes, "Hmm, you. You win." And the problem is, for societies without laws, you do that enough times and then the king says, "Hmm, you're in my family. You win." And so that sort of problem was happening in Athens where justice was blatantly unfair and so what Solon did is he brought a system of laws that would apply for everybody. And so he brings the concept of universal law that applies equally and the same to everybody in Athens. And it's funny how that has survived as an essential and elemental concept in learning today.

I commented, and not purely in jest, when talking about assessment. I want to change the system of assessment in schools because right now we have tests and things like that that are scrupulously fair, particularly distance learning where we outline the objectives the performance metrics and the outcomes and all of that. I want to scrap that system. I want testing to be done by at random by comments from your peers and other people and strangers based on no criteria whatsoever and applied unequally and unfairly.

And people say, "Well, why would you want that?"

And I said, "Well, that's the way the world works."

But the point of that remark is to try to pull apart this idea of universality, everything being the same and learning. Do we need, as is suggested, do we need the iron hand of justice in our classrooms?

Groups – groups are defined by their unity. In fact, one of the first things you do in a group is you try to maintain its unity. A group need to be, in some sense, cohesive, united, "e pluribus unum". Or to keep this politically fair, "The people united will never be defeated," the "melting pot", the encouragement to be the same, the encouragement to have the same values, to follow the same vision, to be, in some relevant way, like the others because that's what the group is. Without that sameness, you don't have the group. You have anarchy.

And we have technologies specifically designed for the group, pre internet technologies appeal to the mass and you're familiar with these – mass broadcasts of television, of radio, newspapers, books. These are things that create the identity of the group and therefore, because the nature of the individual is the same as the nature of the group, it creates the identity of the group.

Think about, in your own country, have there been these moments that have defined the country captured on video and played over and over for your children? In Canada it was in 1972. We played a hockey series – Canada against the Soviet Union. They were evil. We won. It was great. Paul Henderson's goal, I can almost like hear and recite back the play by play announcer. I watched that game sitting in an open concept classroom in Metcalfe, Ontario, with about 50 other kids on one of those little TVs way up on the little rolling stand. And when Henderson scored that goal, we went nuts. And it defined our generation. Unity.

Online, we do pretty much the same thing. We have technologies that appeal to the mass and are used to create unity. All-staff emails – how many of you got an all staff emails? I was talking with Brandy before this talk, she got an all staff text message. An instant message sent to everybody in the ‘buddy list', 200 people or whatever got the URL for the corporate website, the portal. These are "all" things, out of many, one. Out of all these staff and employees in your company or your university or whatever we're gonna have this website and this website will speak for all of us.

Networks are almost defined by the opposite, defined by their diversity. A network thrives on diversity. It wouldn't be a network without diversity. To each his own, so goes the saying, and I know it's not gender neutral, but it's a very old saying so I was faced with a choice. Do I quote the quote accurately or do I put it gender neutral? So I thought I'd quote the quote accurately and then apologize for 30 seconds.

Interestingly, when I grew up, and again I grew up in Metcalfe, Ontario, small farm town south of Ottawa, population 500, we were feral. We roamed the fields and the forests and if there were deer we would have chased deer, but there were cows, so we chased cows. And our teachers would teach to us that Canada was different from the United States. And much later on, I realized, oh, that is Canadian identity.

And the United States, like groups, constitutes a melting pot. In Canada, we were all taught, is a salad bowl where each entity, the lettuce, the tomato, the whatever, cucumber, I don't know what you put in salads. That's what we put in salads. All of these things maintain their distinctness and their identity and by maintaining their distinctness and identity, they create a whole that is something distinct and different from any individual entity and indeed, something that cannot be created without maintaining that distinctness and identity.

And the more I thought about this, you know, I struggle with myself all the time and I wonder, was it indoctrination or were they right? And after many years, I've come to the conclusion they were right.9 And so there is this idea of the network, there is this idea of distinctness and diversity in an environment where people are encouraged not to be the same, but to be different. I like to think I have fulfilled my teacher's expectation, having internalized the encouragement not to consume and to absorb the message from the mass media, but to create, to be that media, to be the artist, to be the writer, to be the videographer. Canada routinely wins awards for its documentaries. We are the nation of documentary makers. I even made a documentary recently.10 Why? Because well, I'm Canadian. I had to. It's in the contract.

Network technology that includes diversity, encourages diversity, talking – talking is wonderful and talking is not a mass phenomenon – telephoning, writing letters, personal emails, do you see what characterizes these things? Right? They're not one to many, they're one to one, and sometimes in the internet age, they're also many to many.

But the idea here is that what defines these things is the set of connections between the individuals and not the content of what's going out. If you try to define what you mean by, say, telephoning or letter writing by the content of the messages, how would you do that? They're not even all in language, especially not with sending pictures and things like that.

Internet technology that encourages diversity rather than conformity includes things like personal home pages or these days, blogs. I should add to this slide MySpace profiles and things like that, your account on Flickr. All of these things that allows the individual to express themselves rather than the individual being part of some larger entity. It's funny, I have an email address, surprise. My email address is stephen@downes.ca.

And I'm just curious now, almost all of you will have email addresses. For all of you, how many of you have an email address based on your institution, college, universities or whatever address? In other words, you know, fred@somepolytechnic.edu or whatever? Where is your personal identity? Why the email? This is your email address. And yet your email address is your institutional address. How did that come to be? Imagine if your personal mail address, the mail that you get from your grandmother, came through your employer and had to be sent to your employer before it got to you. It just seems odd.

Groups require coordination. They require a leadership or a leader which is why we get all of this stuff on leadership. It's the funniest thing, all these things on leadership, because I read these and it's like everybody needs to be a leader, but my experience of groups is usually one leader and a bunch of followers and, you know, I want to see the new business book that says, "Everyone should be a follower." But no. I always look at these things from the point of view of the follower.

People think about groups and leadership and direction and responsibility and they usually mean "my leadership, my direction, responsibility to me." And I look at groups differently because they don't let me lead groups. I look at groups as somebody else's leadership, somebody else I'm responsible to. I have to follow his or her vision, as being "responsible" assumes that I'm under somebody. People picture groups, but they don't picture them in terms of their actual role in the group. They picture them in terms of the role they would like to play in the group. It's a philosophy of aspiration rather than a philosophy of reality.

This is something that socialists need to look at because socialists appeal to groups. They appeal to the worker, but nobody wants to be a worker. That's why socialists, at least in my country, get like 16, 20 percent of the vote. You know? I'm surprised 16, 20 percent of the people identify, "Yeah, I'm a worker." But, you know, people don't want to be a worker. They want to be a manager or retired, one or the other. Socialists speak to neither of those.

A group is defined by its values. I said yesterday and I say it again today, the person who came up with the concept of the vision statement should be thrown out the window. Because think about it. You're in some institution. The powers that be from on high come down with a vision statement. You read the vision statement. How many of you go, "Yeah, that's my purpose in life?" And what follows is a long, protracted exercise to get you to replace whatever vision you had with the vision of the group. And it seems odd. Groups define standards. Groups define belonging.

In learning technology – most of learning technology is intended to support this picture – we have the learning management system. Managing learning. If you think about that, think about what that says to manage learning. What does that mean? It means there'll be a manager of learning. It means that there'll be one person responsible for the learning and everybody else will follow. Learning design, where the learning is organized, sliced, diced, flaked and formed and you follow in a row or you're not a learner. You're an anarchist. Learning object metadata, the 87 or whatever fields to describe a learning object, a learning object being something that can be assembled like a Lego, like individual entities in a group, and this is the one and only way to describe learning resources. And if it's not a learning object metadata, it doesn't exist.

Networks, by contrast, require autonomy. That is to say each individual in a network operates independently. That does not mean they operate alone. What that does mean is – because remember, it's a network, you're connected, you talk to people, they talk to you – it means you define your vision. It means you define what's going to be important to you, your values and interests. It means that when you go to work, the reason why you're at work is because you want to put food on your table, not the boss's table. The boss getting food on his or her table, that's just an accident. But that's not why you're there.

Interaction in a network isn't about leaders and followers. It's about, as I say here, a mutual exchange of value. And my employers don't like me that much because that's how I view myself as an employee. And I go into there and they say, "Well, we're gonna give you these orders now."

And I sort of say, "Well, what are you going to give me for doing that?"

And they say, "Well, we pay you."

I say, "Well you paid me before. You know, we already had an agreement and now you're changing the agreement and that's fine. You can change the agreement, but now I want some changes too." Because it doesn't work that way if this is a mutual exchange of value. You can't just change the condition. I hear so many people say all the time, it was even in my email this morning, it was stuff about networks and that and people say, "Oh, but we're in this institutional environment. We have to do what we're told."

And my response is, "Who said so?" I mean, why? I mean the worst thing they could do is fire you and then you'd be free, but if you belong to a union (another group, right?) you can actually set one group against the other and not follow their orders and still manage to be able to eat and house yourself.

And it's a fascinating – when you reframe these things – you need to reframe these things. Think about the arrangement that they have set up for you. You will do what they say or you will be forced to be homeless and starve. What kind of bargain is that? Right? So this objection is, "we have to do what we do or they won't pay us." But the only people who can change that arrangement is you. Your bosses aren't going to change it. Trust me.

People don't follow, they don't do what they're told in a network. They interact. They make their own decisions, but not completely independently all on their own, not all by their lonesome. They interact with other people. But they make their own decisions.

It's like traveling from Auckland to Wellington. Right? There's different ways you can do it. I mean you can travel with a tour group or you can take the bus. Right? Taking the bus doesn't mean that you're traveling alone. It just means you're not traveling with the group, but you still interact. But your interaction is different. Now it's in a mutual exchange between you and the bus driver or you and the bus company. And I give them money and they said, "Yes we will take you to Wellington and we won't leave you in the desert." And I said, "Good, because it's a nice desert, but I don't want to be left there."

And you think about the technology now that encourages autonomy rather than conformance. E-portfolios is being touted as this sort of technology. The same with the personal learning environments (and you might not know what that is yet because they're new, but if you look that up on Google, you'll find stuff on personal learning environments) and that's the autonomous answer, the network answer to the learning management system. And it's based on a radical concept. Students can learn autonomously. Who would have believed?

But if you read and listen to all this pedagogical theory, it's like, "gee, if we don't take them by the hand and lead them through this, they'll be hopelessly lost and they'll never learn anything at all."11 And if that were true, the internet never would have been built. There were no classes on how to build an internet before it was built. How did they learn? Well, they learned on their own, self-directed.

Groups are closed. This is the ‘walls' part of it. They require a boundary that clearly defines the distinction between members and non-members, otherwise there wouldn't be a group. They would not even a mob, because a mob at least has a border. Groups have memberships. Membership has its privileges. They have logins and passwords and authentication and blood type passes. They have control of vocabularies and standards, jargon. They have in-jokes. You will use this technology. I'm a Mac person. I'm a PC person. Staying on message, he's a loose cannon, he's not part of the group. We speak as one. With one voice we speak. That's what a group is.

A group defines itself with very precise limits. Look at the limits. Look at the boundaries. Look at the walls that you have in your learning environment today, your learning technology environment, even your learning environment today. Look at the walls here right. We've managed to keep all the other people out. Right? And if somebody who was just walking on the street tried to come in here, sit down and listen, we would stop them. Think about that. That's our theory of learning. If somebody wants to come in and listen, we stop them.

Enterprise computing, federated search, federated search is a system whereby you search only accepted resources, resources that have been approved, qualified and typically are commercial and for sale. User IDs and passwords, copyrights, patents, you cannot use that shade of green it's owned by BP. You cannot use the word Coca Cola, not even to talk about Coca Cola because we own that. I can say ‘elearning 2,0' I invented the concept web 2.0. You can have a conference, but you cannot call it web 2.0. I'm blackboard, I invented the learning management system. We will put a wall around anyone else trying to do it.

And even whether or not it's true or not true, it doesn't matter. You build the wall and it becomes true. Assertions of exclusivity define groups. Networks are the opposite of that. Networks are open. Networks require that all entities in the network be able to both send and receive. To send and receive, first of all, in their own way, because they're diverse, and secondly, without being impeded. Well, oddly, that is a radical concept.