Nov 06, 2011

Abstract

In this paper two perspectives of open educational resource are considered, one from the perspective of a person who owns or produces the resource, and the other from the perspective of the person who requires access to the resource. The former model, it is argued, does not take into account the various dimensions of openness, and is vulnerable to various ways of closing access to resources.

In an effort to address the barriers to open education, a new form of online learning, the 'Massive Open Online Course', was developed by the author and his colleagues. The MOOC is designed according to the principles of self-organizing networks of entities. A series of MOOC-based courses have been offered since 2008. An observation of these courses shows widespread production and use of open educational resources within these courses.

It is suggested that by understanding the use of open educational resources as 'words' in a language used by participants in a MOOC to communicate with each other we can explain the role of OERs in personal learning. A course offered as a MOOC is instantiates the properties of a self-organizing network and as a result is resistant to the forces that limit the effectiveness of traditional OERs.

The Idea of Openness

The central argument of this paper can be summarized as follows: learning and cognition take place in a network, and networks need to be open in order to function, therefore, learning and cognition need to be open.

To the former point we address the major tenets of the pedagogical theory known as connectivism (Siemens, 2004). "Connectivism is the integration of principles explored by chaos, network, and complexity and self-organization theories… The starting point of connectivism is the individual. Personal knowledge is comprised of a network, which feeds into organizations and institutions, which in turn feed back into the network, and then continue to provide learning to individual. This cycle of knowledge development (personal to network to organization) allows learners to remain current in their field through the connections they have formed."

As Siemens writes, "A network can simply be defined as connections between entities. Computer networks, power grids, and social networks all function on the simple principle that people, groups, systems, nodes, entities can be connected to create an integrated whole." Connectivism as it is typically presented encompasses the description of learning as it occurs in two major types of network. First, it describes the conditions conducive to learning in a synaptic network, as is characteristic of the human brain. (LeDoux, 2002) Second, it describes the conditions conductive to learning in a social network, as is characteristic of a learning community. (Watts, 2003)

To the latter point we address the need of entities in the network to be able to communicate in order for the network to function. A network is not simply a system in which the entities are joined or related in some way. For a connection to exist, it must be possible for a change of state in one entity to result in, or have as a consequence, a change of state in another entity. In a simple case, for example a Hopfield net, one entity in the network may exhibit an excitatory or inhibitory effect on the other. (Hopfield & Tank, 1986)

Openness, then, is in the first instance the capacity of one entity in a network to change or influence the state of another entity in the network. However, in the fields of content management and online learning, the concepts of 'open' and 'open educational resources' have had a much wider connotation.

Much of what is written with respect to open content and open systems is derived from Richard M. Stallman's original definition of what he called "free software" as four elements (Stallman, 1994):

- Freedom to run the software

- Freedom to study the software

- Freedom to distribute the software

- Freedom to modify the software.

This is a definition that has carried over into the open educational resources (OER) movement. David Wiley's original open content license, for example, as based on "the premise that non-software content – specifically educational content – should be developed and shared in a spirit similar to that of free and open software." (Wiley, 2003)

Definitions based on Stallman's four freedoms, however, may be open to challenge. When people talk about open source software they talk about openness and freedom from the perspective of the person who already has the software, who already has it in their hands and wants to do things with it, like read it, share it, or modify it. And anything that restricts what they do with it is considered an infringement on the freedom. It gives the user the flexibility to do what they need in order to get work done." (The Debian Foundation, 1997)

The difference between these two models comes to a head with respect to commercial use. According to some, a license that prohibits the sale of software is a limitation on its freedom. The Debian Foundation, for example, argues, "There is no restriction on distributing, or even selling, the software. This last point, which allows the software to be sold for money seems to go against the whole idea of free software. It is actually one of its strengths. Since the license allows free redistribution, once one person gets a copy they can distribute it themselves. They can even try to sell it." (The Debian Foundation, 1997)

But what of people who do not have the software, and need the software? The four-freedoms definition of freedom begins to change because, from the perspective of someone who does not have the software, freedom would be open access to the software with no restrictions. Anything that infringes on that open access is a restriction on their freedom.

In my contribution to an Open Educational Resources debate hosted by UNESCO I described an alternative approach to open licensing. (Downes, 2011) I described my own content license, which was in turn derived from the licensing practices of George Reese, the creator of the Nightmare MUD Library. The licensing arrangements for MudLibs were created, not with coders and programmers in mind, but with MUD players. As George Reese writes,

"Since all drivers except DGD were derived from LPMud 3.0, they all require a copyright at least as strict as that one, which basically states that you can use the server as you like, so long as you do not make a profit off of its use. Most current servers have much more strict and explicitly copyrights. On top of that, many of the mudlibs which exist also have similar copyrights. To require money of your players is therefore a violation of international copyright laws. DGD requires licensing through a third party company." (Reese, 1998)

As I noted in the UNESCO debate, Lars Pensjö, who wrote the original LPMud (Bartle, 2003, p. 11) in 1989, wanted to ensure free access to MUDs for the players. As the original MUDOS license stated, "Permission is granted to extend and modify the source code provided subject to the restriction that the source code may not be used in any way whatsoever for monetary gain." (mwiley, 1999) As the discussion makes clear, this is not a prohibition against the recovery of reasonable expenses. It is intended mostly as a prohibition against one person using another person's work for profit.

The importance of this has become clearer 20 years later with when we look at what has become of the online multi-player role-playing environment. The license conditions weren't respected. As Richard Tew (Donky) writes, "That's the thing with releasing mudlibs, people make a few trivial changes and then decide that it has changed so much that it is effectively something completely new." (Tew, 2010) After appropriating the idea and (often) the source code, the commercial sector came to dominate the world of multi-player role-playing games. Today, if you want to play, you pay.

It is not necessary to establish that one or the other of these interpretations is 'correct' in order to establish that there are different meanings of the term "open" depending on one's perspective. So the question is, what is the correct perspective to be looking at, or looking at the issue from, in the context of learning, and online learning in particular?

The Challenge: Making Things Unfree

As noted above, it may be argued that the non-commercial condition attached to an open license means that the content isn't really free. But from another perspective, it can be argued that if someone is charging money for access, then the content is not free, neither free in the sense that it does not have to be paid for, nor free in the sense of being able to use it as one wishes.

A common response from the defenders of commercial use has always been that the content is always available for free somewhere. For example, D'Arcy Norman can be found arguing that commercial use "does nothing to push content into commercial exclusivity, and I would argue gives a relief valve against it – the original content is always available for use, re-use, etc… without having to give a penny to the opportunistic monetizer(s)." (Norman, 2010) So it doesn't matter if, say, Penguin sells a copy of Beowulf because Beowulf is in the public domain and readers can always get it for free somewhere else.

Against this response it may be observed that when there is commercial use of free resources there is significant motivation to prohibit or prevent the free use of these resources. So even if theoretically it is the case that there could be free copies of Beowulf, the commercial publishers of Beowulf may devise mechanisms to prevent or discourage access to the free version. As a result, an entire infrastructure has been created, drawing on community support to foster the creation of open content, and then leveraging market mechanisms to commercialize this content.

For example, my own study of models of sustainable open educational resources and what I found was that most of the projects that produce open educational resources are publishing projects. (Downes, 2007) The resources are coming out of either commercial publishing houses, or universities that traditionally feed materials into commercial publishing houses, or foundations. And the different models for the sustainability of open educational resources were all based around that paradigm.

So for example there is the endowment model. This model is used by the Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. A sum of money is invested and draws interest, and the earning from interest are used to publish the resource. (Loy, 2009) Another is the membership model, where fees for membership in a consortium are charged, and members participate in the creation of the resource.

Another model is the donation model. We see Wikipedia using the donation model. National Public Radio uses the donation model. And again, it's based on this idea that there will be some organization that does some publishing.

But even if you have these free resources hanging around commercial publishers still manage to get you to pay for them. And there's a variety of ways they do this:

But when people pay for memberships they usually expect privileges, and that typically means some sort of privileged access.

- Lock-in – If a user is locked into a certain technology, such as, say, iTunes, or the Kindle, then the material which would normally be available for free is, within that environment, only available at a price.

- High bar – Stringent but unnecessary conditions make free distribution unaffordable. For example, a service might require that learning object metadata, which has 87 or so fields, must be filled in for it to be registered. The commercial publisher can afford to hire someone to sit there and fill metadata fields, but free content providers don't have that kind of resource..

- Flooding – Another way of making users access the commercial content rather than the free content is 'flooding'. This can be observed by doing a search at Google for information on popular topics of learning – language learning, for example. The listings are flooded with search-engine optimized commercial resources, to the point that any free resources have been pushed far down the list.

- Conversion – Providers give users a free resource, and then convert it to a commercial resource, and then get them to pay for it, because they've become dependent on the free resource and can't bear to be without it.

There can be disagreement with the details of this characterization, but it becomes evident from the proliferation of such practices that there is an entire economy of free, of commercial, of publishing, of subscriptions, a whole infrastructure which is surrounding the idea of putatively open educational content. It's open educational content "to a degree, with restrictions, if circumstances permit, using certain technologies." Otherwise we're strangled in the whole – well, as the picture goes, the interests of industrialization, work, images, etc.

And that's the story of open educational resources. Understanding the numerous other dimensions of openness also helps us understand additional ways the resources can be unfree.

Dimensions of Openness

In our work in connectivist courses, George Siemens and I have depicted the progression of openness in three major stages:

- First of all, openness in educational resources

- Secondly, open courses, and then

- Third, an as yet unrealized openness, openness in assessment. (Downes, Notes on open government, open data and open pedagogies , 2011)

This is similar to the five stage 'logic model' proposed by James C. Taylor (Taylor, 2007) and later adopted by the Open Educational Resources University (OERu) (Day, Kerr, Mackintosh, McGreal, Stacey, & Taylor, 2011):

- Learners access courses based on OER

- Open academic support by 'Academic Volunteers International'

- Open assessment by participating institutions

- Participating members grant credit for courses

- Students awarded credible degree or credential

In these two models we see three distinct forms of openness: of access to learning resources, of instruction, and of assessment and credentialing. Sir John Daniel, the former president of the United Kingdom's Open University, describing 'dimensions' of openness, refers to the openness as related to openness of access or admission to a university program, open resources, and then openness in being able to determine your own educational progression, your own course of studies. (Daniel, 2011)

Additional literature brings to bear discussion of additional forms of openness. In order to understand the importance of openness to networks in education, we may identify these systematically.

Open Curriculum – The list of topics to be studied, or competencies to be acquired, or methodology by which learning is to be achieved, may be a more or less open resource. Arguably, MIT's OpenCourseWare was as much an advance in open curriculum as it was open courseware, as it now became evident to all just what MIT students studied in order to obtain MIT degrees. The South African Curriculum Wiki, no longer extant, was an early example of this. (Richardson, 2005)

Open Admission – Open admission, as documented above, is a process whereby a person is not required to offer evidence of previous academic standing in order to qualify for access to a learning opportunity.

Open Standards – In education there's a variety of standards intended to facilitate how we describe, how we discover, and how we reuse educational resources. The central of these is called learning object metadata, or LOM, created originally by the Aviation Industry Computer-Based Training Committee (AICC), and then passed on by Instructional Management Systems, or IMS, and then standardized under IEEE, and then really standardized under the ISO standards organizations.

But there are other standards as well: Learning Design, Common Cartridge, and Learning Tools Interoperability. The United States military, under the auspices of Advanced Distributed Learning (ADL) came out with the Sharable Courseware Object Reference Model (SCORM), which is the standard in commercial online learning.

In some cases these standards are what typically be called 'open', while in others they are more proprietary. IMS, for example, supports itself with a membership system. Members that pay fees have access to the standards ahead of their formal release. IEEE by contrast posted the Learning Object Metadata standard openly while it was still being discussed and decided upon, but charges a fee for the finished product.

Open Source Software – Open Source Software has had a significant impact on online learning. Widely known is Moodle, a PHP-based open source learning management system created originally by Martin Dougiamas with the support of thousands of volunteer programmers. Moodle is small, portable, and useful for colleges and schools. By contrast, the open source Sakai was built by a consortium of universities as part of MIT's Open Knowledge Initiative and is a large suite of enterprise software.

Other open source education projects include Elgg, which is an open source social network software for learning, Atutor, LAMS (Learning Activity Management System), School Tools, and more types of software are available at Schoolforge or Eduforge

Open source software is released under one or another type of open source license. To overgeneralize, one sort of open source license, such as the Berkeley Software Distribution, allows open source software to be integrated into commercial while the other, such as the GNU General Public License, does not. In practice, open source software licensing is a thicket of options and permutations.

Open Educational Resources – More specific to most of the papers in this volume are the open educational resource projects themselves. Here we list just a few of them. One of the earlier ones, and certainly the most famous, most heavily promoted, is MIT's Open Courseware project (OCW). Something that's also received a lot of attention recently (because he appeared on the TED videos) is the Khan Academy, which is a whole series of YouTube videos on mathematics, physics, and similar science and technology subjects. MERLOT is a project that was created by a consortium of North American educational institutions.

These are just a few of dozens of projects that have been set up specifically to create educational materials for distribution for free (or some version of free) to people around the world.

The licensing of these resources, in order to make them available for use and reuse, was based on the GNU Free Documentation License (GFDL), which covered documentation associated with open source software. The GFDL did not allow for some types of restrictions, most notably, the 'non-commercial' restriction.

More recently we've had Creative Commons, and Creative Commons is now arguably the dominant mechanism for licensing open educational resources, and indeed, for licensing open content of any sort. Devised by lawyer Lawrence Lessig, Creative Commons provides the licensor – the person who owns the material – with a series of choices allowing the author "some rights reserved. These include the non-commercial clause, an attribution requirement, share-alike, and a no-derivatives clause.

By far the most popular form of Creative Commons license is the one that I use, "Creative Commons By Non-Commercial Share-Alike," which means that I want to be attributed, I don't want the content to be used commercially, and I want it to be shared under the same license that it was obtained under.

Open Teaching or Tutoring – Open teaching is the provision of live access to teaching activities or resources. As access to a TED video, for example, might be access to the resource, being able to watch a TED talk live – whether in person or online – is access to open teaching (though, of course, TED learning opportunities are manifestly not open). Open tutoring extends this idea to include openness of interactivity with the instructor or tutor.

MOOC Design Principles

It is evident from the discussion thus far that though much of the attention focused around open learning has been on the publication of open educational resources, there are different perspectives and a range of types of openness to consider.

The concept of the Massive Open Online Course, or MOOC, was designed with these wider considerations in mind. It therefore focused not on the narrow question of licensing and distribution of course materials, but on the wider question of promoting and preserving openness across all dimensions.

In order to best accomplish, the MOOC is designed as a network, rather than as a linear progression of subject materials or curriculum. In this way, all aspects of the course are distributed across all participants, rather than centralized into a single location.

A network is composed of a set of entities (also sometimes called 'nodes' or 'vertices'). Entities form connections (also called 'edges') with each other. The internet, for example, is a network, and network course design parallels that of the internet. (Spinelli & Figueiredo, 2010) The 'vertice' and 'edge' terminology is from graph theory, from which the course design is also derived. (Diestel, 2010, p. 2) Networks of connected entities can arguably perform cognitive functions, and correspondingly 'connectionist' computer systems are intended to emulate the functioning of a 'neural network' such as the human brain. (Stufflebeam, 2011)

These principles have been described in previous work (Downes, Learning Networks: Theory and Practice, 2005) and may be summarized here as follows:

– decentralization – connections are organized into the form of a mesh, rather than the hub and spokes more characteristic of a hierarchy

– distribution – the representation of concepts or ideas is not contained within a single node, but is distributed across a number of nodes

– disintermediation – direct communication from node to node is possible and encouraged

– disaggregation – nodes should be defined as the smallest reasonable component, rather than being bundled or packaged

– dis-integration – nodes in a network are not 'components' of one another, and are not depicted as being organized as components of a 'system'

– democratization – nodes are autonomous, and a diversity of node type and state is expected and encouraged, membership and communications in the network are open, and meaning is generated interactively

– dynamism – the network is a fluid, changing entity and demonstrated plasticity – the ability to create new nodes and connections

– desegregation – though the network may exhibit clustering, there is nonetheless a continuity across the network, as opposed to a strictly modular design

Employing these principles an organization was developed that created several types of entities: persons (i.e., people registered for the course), authors (i.e., creators of learning resources), posts (entities created by course authors), links (entities created by persons and authors), files (audio, video or slide multimedia) and events.

The course proceeds by means of seeding the network gradually through time with posts, encouraging persons to connect with these resources and with each other through the creation of posts and links, connecting participants in real time via hosted events, such as online lectures by guest speakers, and the creation and capturing of multimedia files.

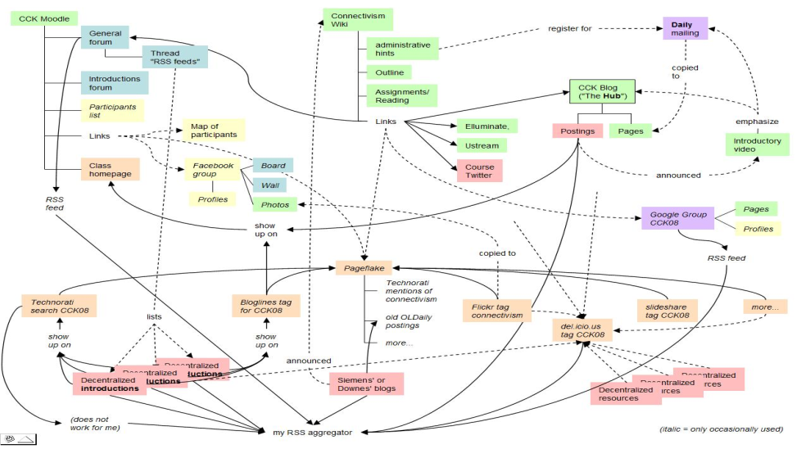

That the MOOC, as described, constitutes a network structure becomes evidence through analysis of the structure of the MOOC. Illustrated below, for example, is the structure of the initial seeding provided by course facilitators:

Figure 1. Network structure of a MOOC. X28's New Blog, 6 September, 2008. (Melcher, 2008)

The deployment of a MOOC as a learning environment has been documented in numerous places elsewhere (Kop, Fournier, & Mak, 2011); what is important in this enquiry is the role being played by open educational resources in the course structure to produce the dimensions of openness described above.

Evidence of OER Production and Use

There is significant evidence extant that one of the primary activities of participation in a MOOC is the use, reuse, and production of open educational resources, so much so that the pedagogy of the MOOC is also referred to as the "pedagogy of abundance." (Kop, Fournier, & Mak, 2011)

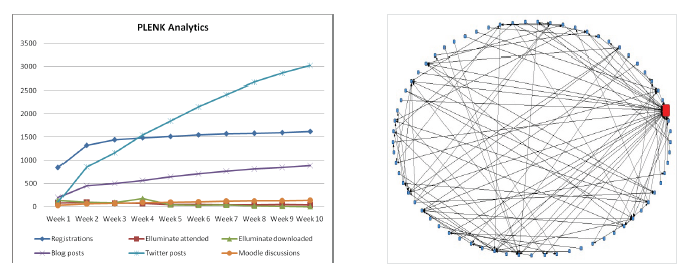

As demonstrated in Kop and Fournier's analysis of a recent MOOC, 'Personal Learning Environments, Knowledge and Networks (PLENK) 2010', participants submitted numerous blog posts, and their discussions around these posts took the form of a network, as may be seen here:

Figure 2. PLENK participation rates. Figure 3.Connections between participants in a discussion. (Kop & Fournier, 2010)

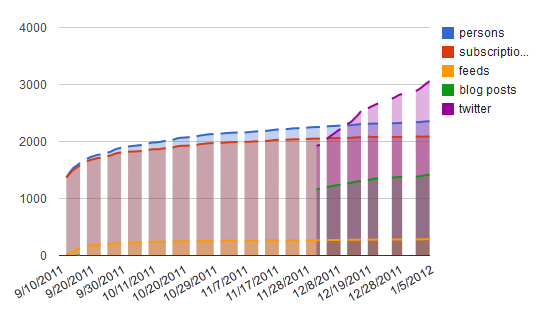

In the more recent #Change11 MOOC (http://change.mooc.ca) we see even greater levels of creating and communicative activity. The chart below measures cumulatively the number of feeds, the number of blog posts, and the number of Twitter posts made by course participants, as well as the level of participation by sign-ups and newsletter subscriptions:

Figure 4. #Change11 participation rates. See https://docs.google.com/spreadsheet/ccc?key=0Aoxh9wWyk71HdGtEYXFfXzdON3Fvb3h2WHFJbTBxMkE&hl=en_US#gid=3

Note that day-by-day counting of blog and Twitter posts started in early December, and by that time had already numbered in the thousands, including 1422 blog posts. As the course progressed through to January, the numbers of each steadily increased, showing a continued engagement and production of course artifacts.

Preliminary analysis of the #Change11 suggests that, as in the case of previous MOOCs, a substantial number of external learning resources are being referenced and linked. Half way through the #Change11 course, for example, the participants in their 286 feeds had linked to 5,150 media artifacts, as evidenced from this course environment printout:

Figure 5. #Change11 media artifacts.

Participants are reading each other's blog posts, both directly and through the email newsletter distribution. Through the newsletter, we can count the number of times readers followed through to the blog post itself, and as of the half-way point we note more than 30 posts having more than 100 click-throughs each (see http://change.mooc.ca/popular.htm).

It is important to take note of two salient features of this activity. First, none of it is assigned reading, nor does any of it appear in the course syllabus. Contents in the MOOC software are, as noted above, separated between what administrators provide to seed the course, and what participants contribute themselves. And second, all of it is hosted, and obtained from, sources external to the MOOC environment, which – because it is openly accessible – makes it all open educational resources.

Adding up these numbers (noting that they do not include comments on blog posts or material referenced in those comments, nor materials read or referenced in venues outside the course environment) and not including Twitter posts gives us 6472 open educational resources implicated in the course thus far. Granted, a significant number of these (and especially of the media resources) will be trivial. The picture is nonetheless one of significant dynamic creation and exchange of open educational resources.

The PLENK course and #Change11 course are not anomalies. Other MOOC courses also result in the creation and exchange of artifacts in this way. It will be the subject of further research to identify factors impacting the nature and rate of artifact creation and exchange. But it's clear it can be significant.

Jim Groom's 'Distributed Storytelling 106' course uses the tag '#ds106', and a Google search on '#ds106' (as of this writing) yields more than 200,000 results. The 'assignments' page, where students' work is aggregated from external sites where it has been posted, contains almost 7,000 items (699 pages of ten items each as of this writing; http://ds106.us/page/699/

It is clear from these examples that when a course is designed according to network principles, and hence as a MOOC, the role of open educational resources changes dramatically. Far from being published materials created by academics and authors and merely consumed by course participants, they begin to become the way in with these course participants communicate with each other, and as a consequence, their use and exchange numbers not in the single digits, but rather in the hundreds or thousands.

The (Open) Language of Learning

And this very point, this very distinction is the distinction between what we might say are old and new depictions of open educational resources, or educational resources generally.

The picture presented above of open educational resources as things that are published, things that are presented by publishers in a very formal manner, probably charged-for and commercial, is the old static coherent linear picture of the world. It's not the model that we want to use for open educational resources, because it's not applicable in a network learning environment.

And that brings us back to what we want to think about in open educational resources. Open Educational Resources are a network of words that we use in whatever vocabulary we're using to conduct whatever activity it is that we're doing or that we're undertaking. They are the signals that we send to each other in our network.

If that is so, then what openness means in the context of open educational resources is whatever is meant by openness in a network, where we think of openness in a network as the sending of these signals back and forth, the sending of these resources back and forth.

We need to think about open educational resources not as content but as language. We need to stop treating open educational resources or online resources generally as though they were content like books, magazines, articles, etc., because the people who actually use them – the students and very often the creators – have moved far beyond that. Each one of these things is a word, if you will, in this very large post-linguistic vocabulary. They are now language. They are not composed of language, they are language.

And that's why they need to be open.

Suppose that everyday words that people wanted to use like, say, 'cat' – to pick a word at random – were owned by, say, Coca-Cola. Now we have allowed a certain limited ownership of words in our society, but by and large we can't own words. We can't own the use of words to create expression. And even more particularly, imagine if we had to pay royalties to use certain letters. So you could only use the letter 'o' if you paid money to Ford. You could only use the letter 'i' if you paid money to Apple. The effectiveness of language would be significantly impaired.

And the thesis here is that the effectiveness of language would be impaired in exactly the same way the effectiveness of communication would be impaired, in exactly the same way the effectiveness of a network is impaired if you break down or block the links between entities.

The use of open resources in a MOOC is clearly that of a language, where the resources are the 'words' sent back and forth between participants in a dense network of communication. It becomes clear that measures that would impair the flow of these 'words' would damage this communication, and render mute the MOOC itself.

We can, indeed, map the openness of a MOOC – which is open by design – to the various dimensions of openness mapped above.

In a MOOC, the curriculum is the construction of the MOOC itself – the lists of links to individual feeds, posts and links, and other resources shared in the course. Opening these lists makes the structure of the MOOC transparent, and also allows people to participate in the MOOC without ever actually registering in the MOOC (this is a dimension of MOOC participation that has yet to be explored) and creates what amounts to open admission.

The MOOC is built using open standards to facilitate communication and content sharing. Because there is a great diversity of platforms and languages in a MOOC, common aggregation formats are used, and the deployment of open source software (gRSShopper for PLENK and #Change11, WordPress for DS106) allows new standards or extensions to be implemented as needed. They also allow participants to create their own MOOC applications or interfaces.

The most obvious dimension of openness in a MOOC is the sharing of open educational resources, but it's important to recognize that the facilitators, by participating in this network of interactions, open their instruction as well. They do this by interacting bilaterally or with a group with participants in the MOOC, and by creating recordings or broadcasts of these interactions so they may be shared with other participants.

Finally, by virtue of its structure and its sharing of resources in a network environment, a MOOC is resistant to the sort of enclosure that afflicts traditional OER publishing.

Because there is no single environment, and because the MOOC consists essentially of a network of connections between autonomous entities, there is no mechanism for creating lock-in. Any technology employed by a person engaged in a MOOC could be easily exchanged for another supporting the same standards; any content provided by a participant could be exchanged for another.

The network structure of a MOOC also resists the privileging of certain content with high-bar qualifications needed to enter the network. Any participant in the network may contribute content, and as communications may be direct from person to person, there is no intermediating structure to impose a high bar.

Similarly, the flooding of search results and other centralized points of access is no longer an effective strategy for commercial media. Communications are exchanges of content between the participants, and not passive access of media from a centralized repository or store. Hence, there is no list to be flooded, and no mechanism to impose undesired content into the perspective or point of view of the participant.

Finally, the means for conversion are minimal. A MOOC isn't a single entity on which one can become dependent, it isn't located in a single place and doesn't require a key piece of technology. Consequently, there is no means to force a person to pay for access to a MOOC, or any component of a MOOC.

Understanding open educational resources as though they were words in a language used to facilitate communications between participants in a network should revise our understanding of what it means to be open, and what it means to support open educational resources. It is clear, from this perspective at least, that openness is not a question of production, but rather, a question of access.

References

Bartle, R. (2003). Designing Virtual Worlds. New Riders.

Daniel, J. (2011, 03 23). Revolutions in higher education: how many dimensions of openness? . Retrieved 06 11, 2011, from Commonwealth of Learning: http://www.col.org/resources/speeches/2011presentation/Pages/2011-03-23.aspx

Day, R., Kerr, P., Mackintosh, W., McGreal, R., Stacey, P., & Taylor, J. C. (2011). Towards a logic model and plan for action. Retrieved from Open Education Resources (OER) for assessment and credit for students project.

Diestel, R. (2010). Graph Theory (4th ed.). Heidelberg: Springer-Verlag.

Downes, S. (2005, March 8). Learning Networks: Theory and Practice. International Conference on Methods and Technologies for Learning. Palermo, Italy.

Downes, S. (2007). Models for Sustainable Open Educational Resources. Interdisciplinary Journal of Knowledge and Learning Objects, 29-44.

Downes, S. (2011, 05 03). Notes on open government, open data and open pedagogies . Retrieved from Half an Hour: http://halfanhour.blogspot.com/2011/05/notes-on-open-government-open-data-and.html

Downes, S. (2011, 05 08). The OER Debate, In Full. Retrieved from Half an Hour: http://halfanhour.blogspot.com/2011/05/oer-debate-in-full.html

Hopfield, J. J., & Tank, D. W. (1986, 08 08). Computing with Neural Circuits: A Model. Science, 233(4764), 625-633.

Kop, R., & Fournier, H. (2010). New Dimensions to Self-directed Learning in an Open Networked Learning Environment. International Journal of Self-Directed Learning, 7(2), 1-21.

Kop, R., Fournier, H., & Mak, S. F. (2011). A pedagogy of abundance or a pedagogy to support human beings? Participant support on massive open online courses. International Review of Research in Open and Distance Learning, 12(7).

LeDoux, J. (2002). Synaptic Self: How Our Brains Become Who We Are. Viking Adult.

Loy, M. (2009). Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy: Building an Endowment with Community Support. Retrieved 11 14, 2011, from JISC – Ithaka Case Studies in Sustainability: http://sca.jiscinvolve.org/wp/files/2009/07/sca_bms_casestudy_sep.pdf

Melcher, M. (2008, September 6). [CCK08] First impressions. Retrieved from x28's new Blog: http://x28newblog.blog.uni-heidelberg.de/2008/09/06/cck08-first-impressions/

mwiley. (1999, 05 15). Threshold RPG = Copyright Infringment? Retrieved from rec.games.mud.lp.

Norman, D. (2010, 11 19). Comment on 'No, Stephen…'. Retrieved 11 17, 2011, from iterating toward openness: http://opencontent.org/blog/archives/1730

Reese, G. (1998, 10 1). LPMud FAQ. Retrieved from LPMuds.net: http://LPMuds.net

Richardson, W. (2005, May 8). South African National Curriculum Wiki . Retrieved January 9, 2011, from Weblogg-Ed: http://weblogg-ed.com/2005/south-african-national-curriculum-wiki/

Siemens, G. (2004, 12 12). Connectivism: A Learning Theory for the Digital Age. Retrieved from elearnspace: http://www.elearnspace.org/Articles/connectivism.htm

Spinelli, L., & Figueiredo, D. R. (2010). Characterization and Identification of Roles in TCP Connection Networks. IFIP Performance 2010 – 28th International Symposium on Computer Performance, Modeling, Measurements and Evaluation. Namur, Belgium.

Stallman, R. M. (1994). What is Free Software? Retrieved from GNU Operating System: http://www.gnu.org/philosophy/free-sw.html

Stufflebeam, R. (2011). Connectionism: An Introduction. Retrieved from The Mind Project: http://www.mind.ilstu.edu/curriculum/modOverview.php?modGUI=76

Taylor, J. C. (2007, 10). Open Courseware Futures: Creating a Parallel Universe. e-Journal of Instructional Science and Technology (e-JIST) , 10(1).

Tew, R. (2010, 1 4). Sorrows mudlib v1.84. Retrieved 04 17, 2011, from LPMuds.net: http://lpmuds.net/forum/index.php?topic=1102.0

The Debian Foundation. (1997). What Does Free Mean? or What do you mean by Free Software? Retrieved 12 06, 2011, from Debian: http://www.debian.org/intro/free

Watts, D. J. (2003). Six Degrees: The Science of a Connected Age. W. W. Norton & Company.

Wiley, D. (2003, 03 21). http://www.reusability.org/blogs/david/archives/000044.html. Retrieved from autounfocus: http://www.reusability.org/blogs/david/archives/000044.html

------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

As Presented to the Best Practices in Upgrading Online, Calgary, via Adobe Connect, March 29, 2011. Presentation slides and audio.

The very first thing I want to do is to counter the disclaimer that frightened me as this session opened, it was very loud, and said all kinds of things about how this was all private and cannot be shared. You can share this presentation all you want. This presentation is mine and if you want to share it with people, go ahead and share it. No problem at all.

I should have probably put a Creative Commons license on it, although everything on my website is licensed under the Creative Commons license – attribution – non-commercial – share-alike license. So don't feel inhibited from sharing this stuff.

I do want to talk about the role of open educational resources in personal learning. I also want to talk about what they mean in personal learning. I have a challenging presentation ahead, one that I think will make you think, I hope will make you think, and rethink just what it is that we're up to when we take resources like this presentation, and the pictures and the words and all of that, and put them online or present them in a Connect workshop, what it is that's happening there, what it is that we're up to.

The Idea of Openness

Here's the argument in one slide, and the argument from my perspective really is very simple. Learning and cognition happen in a network. And I could go on and on and on about what that means, but basically, first of all, learning happens in your brain, your brain is composed of a network of interconnected neurons, and learning happens in a society, and society is composed of a bunch of interconnected people. We can depict both of those as networks. And, they are networks.

The second thing is, networks need to be open in order to function. If those connections between the nodes and the entities in the network are broken, are blocked, then that network ceases to function. In order to function, communication has to take place from node to node. And this communication needs to be unobstructed. If the communication is obstructed, this is a network failure.

So, the argument for open educational resources is simply: networks need openness in order to function. So we're all done. We can all go home now.

Well, nothing's that simple. What does it mean to say that our network is open? What is openness?

Well, there's Richard Stallman and the traditional definition of open source as four elements (Stallman, 1994):

- Freedom to run the software

- Freedom to study the software

- Freedom to distribute the software

- Freedom to modify the software.

And this is a definition that has carried over into the open educational resources (OER) movement. And it's a definition I think that we need to challenge because we need to consider what the perspectives are on this freedom.

When people talk about open source software they talk about openness and freedom from the perspective of the person who already has the software, who already has it in their hands and wants to do things with it, like read it, share it, modify it, whatever. And anything that restricts what they do with it is considered an infringement on the freedom.

But what if you're a person who does not have the software, and needs the software? Now our definition of freedom begins to change a little bit because from the perspective of someone who does not have the software freedom would be open access to the software with no restrictions. Anything that infringes on that open access is a restriction on their freedom.

And the difference between these two models comes to a head when we talk about commercial use. If you own the software then you should be able to sell it, and if somebody says you can't sell it that's a restriction. But if you don't have the software somebody trying to sell it to you rather than actually giving it to you is creating a restriction.

You have different kinds of open depending on your perspective. So the question is, what is the correct perspective to be looking at, or looking at the issue from, in the context of learning, and online learning in particular.

David Wiley has spoken about open educational resources for many years. He's one of the pioneers in the field. He came up with one of the first open licenses. He talks about openness and standards, and he is again one of the early pioneers in things like learning objects and learning object metadata. He talks about openness in software, and then he talks about openness in system, like open courses.

George Siemens and I, in our work offering online courses, have depicted the progression of openness in three major stages:

- First of all, openness in educational resources

- Secondly, open courses, and then

- Third, an as yet unrealized openness, openness in assessment.

There are other kinds of openness. I was reading something from Sir John Daniel, the former president of the United Kingdom's Open University, talking about openness as related to openness of access or admission to a university program, open resources, and then openness in being able to determine your own educational progression, your own course of studies.

So there are these different dimensions of openness we can talk about, different ways of describing the same concept.

I'm just going to go through those six.

The Open Standards

I'm not going to linger on this because you could spend a lifetime talking about standards. In education there's a variety of standards intended to facilitate how we describe, how we discover, and how we reuse educational resources.

The grandfather of these is called learning object metadata, or LOM, created originally by the Aviation Industry Computer-Based Training Committee (AICC), and then passed on by Instructional Management Systems, or IMS, and then standardized under IEEE, and then really standardized under the ISO standards organizations.

But there are other standards as well: Learning Design, Common Cartridge, and Learning Tools Interoperability. The United States military, under the auspices of Advanced Distributed Learning (ADL) came out with the Sharable Courseware Object Reference Model (SCORM), which is the standard in commercial online learning.

These standards have all had kind of a murky history, they're sort of open, they're sort of not open, they're sort of proprietary, they're sort of not proprietary. IMS, for example, supports itself with a membership system. If you pay them several thousands of dollars, more if you're bigger, then you have access to the standards ahead of time. It's about a year ahead of time. And so you can make all your products line up with the standards, and everybody else has to wait until IMS formally releases them.

IEEE by contrast will release the standards openly while they're still being discussed and decided upon, but once IEEE settles on the formal specification it then removes it from its website and you have to pay them for it. So openness is really murky, as I said, with respect to standards.

In my world the best kind of standards are ones that are completely open, without encumbrances, which is why, out of all of these, I have tended to favour none of them, and instead favoured things like RSS or even Dublin Core, which are much more open and much more freely used.

Open Source Software

Open Source Software has had a significant impact on online learning. I imagine most people are familiar with Moodle, which is a PHP-based open source learning management system is created originally by Martin Dougiamas and then thousands of volunteer programmers. Moodle is small, portable, and useful for colleges and schools.

Another learning management system that was developed as open source software, Sakai, is exactly not that. It's Java-based, it's enterprise, it was built by a consortium of universities as part of MIT's Open Knowledge Initiative. There's Elgg, which is an open source social network software for learning, Atutor, LAMS (Learning Activity Management System), and more types of software are available a Schoolforge. And so on.

And all of these are released under one or another type of open source license. If you're not sure about open source licenses, really – and I'm going to over generalize here – that world breaks down into two kinds of worlds: one where the open source license allows commercial development, and the other, the GPL world, where it doesn't allow commercial development.

Open Educational Resources

More specific to our agenda today are the open educational resource projects themselves. Here I list just a few of them. One of the earlier ones, and certainly the most famous, most heavily promoted, is MIT's Open Courseware project (OCW). Something that's also received a lot of attention recently (because he appeared on the TED videos) is the Khan Academy, which is a whole series of YouTube videos on mathematics, physics, and similar science and technology subjects. MERLOT is a project that was created by a consortium of North American educational institutions.

And I could go on. There are dozens of projects that have been set up specifically to create educational materials for distribution for free (or some version of free) to people around the world.

The licensing of these resources, in order to make them available for use and reuse, used to be based on something called the GNU Free Documentation License (GFDL). That was the license that accompanied open source software originally. You'd have the software, which was licensed under GPL or some other open source license, and then the documentation that came along with the software had its own license.

More recently we've had Creative Commons, and Creative Commons is not the dominant mechanism for licensing open educational resources, for licensing open content of any sort. Creative Commons was devised by Lawrence Lessig and actually providers the licensor – the person who owns the material – with a series of choices. The person may apply some restriction to the license of the material.

For example,

- CC-by: that requires that the person who uses the content attribute the content to whomever wrote it in the first place. So if you use my content, and I've applied the 'by' condition, you have to say, "This content was created by Stephen Downes."

- 'Share Alike' means that if you share the content, you must share it under the same license that you got the content.

- 'Non-commercial' mans that you cannot use the content to make money (and we could talk about that in more detail)

- 'Non-derivatives' means that you have to use the content as it was created; you can't take the content and make changes to it and effectively create derivative materials from it.

By far the most popular form of Creative Commons license is the one that I use, "Creative Commons By Non-Commercial Share-Alike," which means that I want to be attributed, I don't want the content to be used commercially, and I want it to be shared under the same license that it was obtained under.

Making Things Unfree

A lot of people in the open educational resource community say that the non-commercial condition means that the content isn't really free, because, if it were really free then you should be able to charge money for it. But this is the perspective issue again. If I don't have the content, and want the content, and some guy's charging money for it, it's not free, it's not free in any sense of the word. It's not free in the sense that I don't have to pay for it, but it's also not free in the sense that I can't use it if I don't have the money, I just don't have access to it.

The response from the defenders of commercial use has always been that the content's always available for free somewhere. So it doesn't matter if, say, Penguin sells a copy of Beowulf because Beowulf is in the public domain and you can always get it for free somewhere else. But in fact, in my opinion, it's not so simple as that. When there is commercial use of free resources there are all kinds of motivation to prohibit or prevent the free use of these resources. So even if theoretically it is the case that there could be free copies of Beowulf hanging around, the commercial publishers of Beowulf the $4.95 version have all kinds of ways of making sure you just can't get at it. And this creates an entire infrastructure for creating open content and then managing somehow to charge for open content, which to be goes entirely against the whole concept.

I did a study in 2006 on models of sustainable open educational resources and what I found was that most of the projects that produce open educational resources are publishing projects. The resources are coming out of either commercial publishing houses, or universities that traditionally feed materials into commercial publishing houses, or foundations. And the different models for the sustainability of open educational resources were all based around that paradigm.

So for example you have the endowment model. This model is used by the Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. You take a big chunk of money and put it aside, you get interest on that money every year, and you use the interest on the money to publish the resource. Which worked really well until the stock market crashed.

Then there's the membership model, and that's the model I described earlier for IMS, where you charge memberships, and people can join your consortium and participate in the creation of the resource. But when people pay for memberships they usually expect privileges, and that typically means some sort of privileged access.

Another model is the donation model. We see Wikipedia using the donation model. National Public Radio uses the donation model. And again, it's based on this idea that there will be some organization that does some publishing.

But even if you have these free resources hanging around commercial publishers still manage to get you to pay for them. And there's a variety of ways they do this:

- Lock-in, for example – if they lock you into a certain technology, such as, say, iTunes, or the Kindle, then the material which would normally be available for free is, within that environment, only available at a price.

- Another way of making it very difficult to get free materials is to set what might be called a 'high bar' for free content. You pose conditions, for example, learning object metadata, which has 87 or so fields which must be filled in for it to be registered. The commercial publisher can afford to hire some guy to sit there and fill metadata fields, but free content providers don't have that kind of resource, and so the requirement that content have metadata attached to it creates this 'high bar' that free content can't get over, and so the only version of the content you're going to get is the version where somebody paid somebody create metadata.

- Another way of making you access the commercial content rather than the free content is 'flooding'. This is what Starbucks does. When they want to move into a community they look at the downtown area, three of four square blocks, and they put 25 stores in there. You might say no area needs 25 Starbucks, and it's true, but when they put 25 Starbucks in, that drives out all the other competition. Nobody can compete, and once Starbucks has the only coffee stores in the area, now they can start closing stores, raising prices, kicking people out if they're hanging around on the nice sofas, etc. In the world of software, once example is with the commercial versions of Wikipedia. Wikipedia has one of these licenses where you can make a commercial version of it. There are these commercial versions of Wikipedia, and what they do is they take Wikipedia content, put it in a little tiny content window in the middle of the screen, and surround it by advertising, the more flashing and annoying the better. It used to be the case – it's not now because Google stepped in – that if you did a search for a topic that is covered by Wikipedia, you couldn't find the Wikipedia article. All you'd hit were these commercial versions, because they can afford to pay for search engine optimization and Wikipedia can't. Now over time Google stepped in and like the hand of God reaching down elevated Wikipedia up in the search rank, so this doesn't work anymore. For Wikipedia. But it still works for all the other kinds of free content that Google doesn't elevate. You don't notice that. But if you go the next time you do a search at Google and look at the listings, ask yourself how it is that these five are at the top of the list. They've been search-engine optimized. And they're almost certainly, if they're not Wikipedia, they're almost certainly going to be commercial content of some sort.

- There's also 'conversion'. That's where you give somebody a free resource, and then you convert it to a commercial resource, and then get them to pay for it, because they've become so addicted to your free resource that they can't bear to be without it.

So you can see – and you can disagree with the details of this – but you can see that there's this whole economy of free, of commercial, of publishing, of subscriptions, this whole infrastructure which is surrounding the idea of putatively open educational content. It's open educational content "to a degree, with restrictions, if circumstances permit, using certain technologies." Otherwise we're strangled in the whole – well, as the picture goes, the interests of industrialization, work, images, etc.

And that's the story of open educational resources.

The Language of LOLcats

Now I'm going to change gears, and I'm going to change gears really dramatically. What I want to propose to you is that on the internet now the new media that people use - and there's a whole range, everything from little cartoons to videos to animations to those Flash games to the memes that go around to Twitter hashtags and all of that – all of these new media constitute a vocabulary, and that when people create artifacts in this new media they are, quite literally, "speaking in LOLcats."

A 'LOLcat' is – LOL stands for 'Laugh Out Loud' – is typically a photograph, a digital photograph, preferably of a cat, with a funny saying on it. The original is a picture of a cat smiling, looking very smug, looking up at you, and saying "I can has cheezburger?" And there's a whole ethos that goes into LOLcats. There's the bad grammar, there's tying into contemporary memes, there's contemporary ideas, Cheshire Cat, and any of you who have spent any amount of time online know about these, especially these days, the YouTube videos are almost the dominant memes. Even if you don't spend time online, if you watch CTV news, the weather reporter (Jeff Hutcheson) does this "I watch video so you don't have to" segment with these cute videos.

All of these are instances of people, if you will, speaking in LOLcats. LOLcats, or any of these media, are far more than just the image and the words. Here we have a cartoon, one of my favourites, it's XKCD, and it's a neat little story about all of the tech things a person does to contact somebody who is inside the locked room, and of course you can read the punch line for yourself. But is that all the comic is saying? What are the messages? What are the meanings behind the comic?

Here's an instance of something capped Gaping Void. This guy made a name for himself drawing little cartoons on the back of business cards. They don't always mean a whole lot, but then he started putting them up online and they started getting shared a lot, and they're very interesting. So with each one of these we can ask, what is the person saying? What is a person saying when they take one of his little business cards and put it on their own website?

Here's something that was popular not long after 9-11. Some said too soon. As you can see it's the guy now known as 'Tourist Guy' – because they often get generic names like that – photographed on top of the World Trade Center and you can see the airplane in the background. And this is characteristic of this sort of media manipulation where you take two photos, one of an airplane and one of a guy on top of the World Trade Center, and put them together to create some sort of odd statement.

And of course once one of these things gets going it really gets going – there's Tourist Guy in front of the Hindenburg, and there's Tourist Guy, and the plane is still there, but now you have Kanye West jumping in to say that "Pearl Harbor was the greatest attack." And you can see here how the memes, the concepts, the ideas, the images merge, remerge, fold over each other, shape and create new kinds of meaning. And then people share them, and when they share them, they're creating some kind of meaning out of that too. Aren't they? Because they don't do it for no reason, it's not rational to suppose that they do it for no reason.

These are languages. This sharing of the resource is the expression of meaning in a language. And there are all kinds of languages. These digital photographs, these videos and that, are just a few of the many many languages we use in day-to-day discourse.

Body language, for example. Everybody reads body language, some better than others. Me, I'm practically illiterate in body language. People have their strengths. Clothing, uniforms, flags – we've been watching the Libya thing, one of the very first things they did was to revive the old Libyan flag, the red green and black flag with the crescent and star symbol on it. These things have meanings. The hats, the headgarb that people wear, they have meanings. The drapery in the back of the room has meaning. How many people belong to the jeans and t-shirt set? That's almost a uniform.

Maps, diagrams and graphics have meaning, and they don't necessarily have literal meaning. Here we have a graph of the social network environment from 2007 and what it's doing is using the language of maps in order to talk about something that is very much not mappable. Except that it is mappable, because here's a map of it.

What I'm saying is that this sort of thing underlies our thought processes in general. This is a picture on this slide of a drawing on a cave wall in Kakadu National park. I took this photograph in 2004, and if you look at it really closely it's a fish and fish guts. You might ask, why would an aboriginal draw a painting of fish guts on a cave wall. And the answer of course is that he – I assume it's a he – wanted to communicate something about fish guts to other people and this was the mechanism for doing it. It was probably a description of what you'll find inside a fish, what you can eat, what you can't eat. Etc. Whatever was important about fish to them.

And we do this in general. We use these – I don't want to say 'representations' because that's too strong a word – but we use these drawings to communicate with each other. The LOLcats, the YouTube videos, the cave paintings on the wall, the body language, the maps – all of these are functioning in the same way. This means that when we're talking about media, and we're talking about communication, we have to get beyond the way we talk about text and books and chapters and papers and publications. We have to get beyond that very narrow discussion because when we talk about ways we communicate as being very simply text and books and publishers and things like that we talking only about a very small narrow segment of it.

What is this kind of talk that we need to get away from? Think about the assumptions that you may have had not only about educational resources but about communications in general. Something like, "messages have a sender and a receiver." In the world of the internet that makes no sense. It really doesn't. "Why did you publish that picture of a cat with a hot on it?" "Because I could." "Who did you send it to?" "Well I don't know."

Or conceptions like "words get meaning from what they represent." Not so. Words – anything – get meaning from pretty much anything. Or "truth is based on the real world." Or "events have a cause and causes can be known." "Science is based on forming and testing hypotheses." All of these are things that are true in this static, linear, coherent, text-based semiotic-based picture of the world, but it's a picture that, even if it was once correct, is no longer correct. The world is just no longer like that.

And this very point, this very distinction is the distinction between what we might say are old and new depictions of open educational resources, or educational resources generally.

The picture that I presented top you earlier of open educational resources as things that are published, things that are presented by publishers in a very formal manner, probably charged-for and commercial, that's the old static coherent linear picture of the world. It's not the model that we want to use for open educational resources.

We need to think about open educational resources not as content but as language. We need to stop treating open educational resources or online resources generally as though they were content like books, magazines, articles, etc., because the people who actually use them – the students and very often the creators – have moved far beyond that. Each one of these things is a word, if you will, in this very large post-linguistic vocabulary. They are now language. They are not composed of language, they are language.

And that's why they need to be open.

Think about it for a second. Suppose that everyday words that you wanted to use like, say, 'cat' – to pick a word at random – were owned by, say, Coca-Cola. Now we have allowed a certain limited ownership of words in our society, but by and large you can't own words. You can't own the use of words to create expression. And even more particularly, imagine if you had to pay royalties to use certain letters. So you could only use the letter 'o' if you paid money to Ford. You could only use the letter 'i' if you paid money to Apple. The effectiveness of language would be significantly impaired.

And the thesis here is that the effectiveness of language would be impaired in exactly the same way the effectiveness of communication would be impaired, in exactly the same way the effectiveness of a network is impaired if you break down or block the links between entities.

So how do we understand this new media? What – I don't want to say 'skills' – what do we need to know in order to know how to deal with these open educational resources, with these online resources generally? Because, if it's a language, there are going to be linguistic elements.

I've come up with this frame, it borrows from Charles Morris, who gives us syntax, semantics and pragmatics, Derrida a little bit, Lao Tzu a little bit.

Syntax is basically our understanding of the shapes that things can take. It's not just rules and grammar. Rules and grammar is a way of talking about language and linguistic expression, text-based expression. Syntax can be archetypes, can be Platonic ideals, can be grammar, logical syntax, procedures, motor skills, operations, patterns, regularities, substitutivity, eggcorns and tropes, etc. Any of those words is well worth looking up.

We think of rules of language – and it's funny because we think that the rule tells us what to do, but the rule really is just a pattern and has come to be a rule because we've observed it over and over and over. Cause and effect is like that. And the skill here is in seeing and recognizing these patterns. Recognizing them and then being able to manipulate them.

A guy called Saul Alinsky wrote a book called Rulebook for Radicals. One of the things he said was, "use their own rules against them." Because the established order has ways of doing things, and if you follow the ways of doing things you can actually subvert the established order. The trick here is to see what those rules actually are. And then to be able to manipulate those rules to your own advantage.

Semantics. Not just theories of truth, because the minute you get into theories of truth you get into all kinds of things, all kinds of issues: what makes a sentence true? What makes a picture true? What makes a cartoon true? I look at Family Circus and I nod to myself and say, "true." And I know that the characters depicted in Family Circus are completely fictional. It's not just thta, though. What is the meaning, the purpose or the goal of a communications artifact? The connotation or implication of what was said? Or if I send you a picture of a very large turkey, I'm not telling you to go get a turkey. I might not even be calling you a turkey. But depending on our context, there might be some shared meaning between us on that. Three strikes in a row – bowling reference, maybe.

Semantics may be based on interpretation, it may be based on frequency, it may be based on what we're willing to bet. Frank Ramsay came up with a theory of probability based on how much you're willing to wager. Probability P is '4' if you're willing to wager 4 dollars to get 1 dollar back.

And more: forms of association, contiguity, back-propagation. Meaning, semantics and networks. Decisions and decision theory – you talk to the political scientists and economists and they will time and time again go back to a world view based on decisions and decision theory.

Pragmatics. Which means use, actions, impact. J.L. Austin wrote a book called How to do Things with Words. When people talk about freedom of speech, usually they mean 'freedom of expression', not 'freedom of doing'. But there's so much with speech that we actually do – you stand at the altar and you say "I do", you're not just making a statement but you're actually committing an act. If you ask a question, you're not simply uttering some words, but you're creating an expectation of a response. Wittgenstein said meaning itself is based on use.

Cognition. This is another element of this framework. I've defined cognition in four major areas; other people may do it differently, which is fine. Description, definition, argument and explanation. And basically what cognition means the way we transition from one thing to another thing to another thing in our language. It's about the inferences that we make, the explanations that we make, how we go beyond a mere statement of "what is" to a statement of "what must be", to "what could be", "what may be", "what we ought to do", "what we ought to think", etc.

Context. This has to do with environment, placement, localization, language, culture, reference. A lot of late 20th century philosophy was based on discovering the contextual sensitivity to everyday things. Explanation, for example, explored by people like Hansen and van Fraassen. If you say "the roses have grown well," or if you ask, "why have the roses grown well?" what you mean is "why have the roses grown well instead of growing poorly?" Or "why have the roses grown well instead of tulips?" Or "why have the roses grown well instead of aliens landing from outer space?" The answer we get when we ask for an explanation depends on what we though the alternatives were. And that's context.

Same thing with meaning. Willard van Orman Quine explores the question of meaning, the possible range of translations that could take place if we encounter a new language for the first time. Derrida explores the alternatives in a vocabulary space. Frames, as described by George Lakoff. Etc. All of these constitute an understanding of context.

And then finally, change. There are many different ways of depicting change ranging from old Taoism, the I Ching, logical relation, to flow, the idea of change as being directional, change as being manifest in history, Marshall McLuhan examining the four aspects of change. Logic is a study of change. Gaming theory, simulations, and that sort of thing, is a theory of change. Scheduling, time-tabling, activity theory, learning as a network, all of that is looking at things as based in change.

So we take all of this together, wrap this all up – we typically think of knowing, learning, if we don't think of it as retaining content (and I think most people don't any more) we think of it as acquiring skills. Henry Jenkins describes skills like 'performance', 'simulation', 'appropriation'. But these things are all actually languages and should be understood in these six dimensions. Any of the things that we're trying to teach people, any of the things – science, mathematics, social studies, Egyptian philosophy, whatever – should be understood as one of these languages.

So here's an example of one of those frames using Jenkins's skills, so we have 'performance', 'simulation', 'appropriation', and in 'performance' we have the elements of syntax, semantics, pragmatics, context, cognition and change. And then for each one of these boxes we can analyze what the details are of that aspect of that language. So what is the syntax of performance, for example? There are the different forms, patterns, rule systems, operations and similarities in performance. From something very simple as "knowing your lines" to presentation acting, method acting, Stanislavski's system, ritual performance, all of these different ways of formalizing performance. And that constitutes ways of understanding performance.

The (Open) Language of Learning

This reaches the third and final thesis: fluency in these languages constitutes 21st century learning. Being able to speak and write and perform and act and share and whatever these different languages constitutes learning in the 21st century. We use to think there was just acquiring content and we use to think there was just acquiring skill but it's much more involved than that. Actually being fluent in these languages, where being fluent means mastering or being capable in the semantics, the syntax, the pragmatics, the context etc., of these different languages.

And that brings us back to what we want to think about in open educational resources. Open Educational Resources are a network – no, I don't even way to say it that way, that trivializes it - Open Educational Resources are individually the words that we use in whatever vocabulary we're using to conduct whatever activity it is that we're doing or that we're undertaking. They are the signals that we send to each other in our network.

If that is so, then what openness means in the context of open educational resources is whatever is meant by openness in a network, where we think of openness in a network as the sending of these signals back and forth, the sending of these resources back and forth.

When I think of openness in a network I come up with four major dimensions. There may be others. I don't pretend to be authoritative on this, or even original, but these are the ones that I see:

- Autonomy – each entity in the network is self-governing

- Diversity – the entities in the network are encouraged to have different states, to be different things, have different opinions, say different things

- Openness – in the sense that signals can be sent freely from one entity to another, and entities have access to signals that are sent from one entity to another, that membership in the network itself is open and fluid, and then finally

- Interactivity – that what is learned by the network is not constituted in the signals that are sent back and forth but rather what is created by the network as a whole that is emergent from the activities that the entities in the network undertake.

What I mean by that is that what is learned by a brain, for example, is not a bunch of electrical impulses. That doesn't make sense! What is learned by a brain is what emerges when these impulses are sent back and forth between ten or a hundred billion neurons.

What is learned is greater than the content of the individual messages. And that is key and crucial to understanding open educational resources. The resources are not content we expect people to assimilate. The content of these resources is not the learning. The learning is what happens when you take these resources and start interacting with them in a network.

That's the basis that George Siemens and I used to create the massive open online courses. The idea of these courses was that, and is that, we provide as much material for conversation as possible and set up this conversational network where the exchange of this material can take place. So the course itself becomes a network, the open educational resources are the concepts, the words, the vocabulary that people in this network use to communicate with each other. And that's in fact exactly what happens.

Somebody signs up for the course, they start reading stuff being sent by other people, so the idea is we create this network, enable people to communicate using these open educational resources within this network, and the learning people undertake is not the content of these resources, but whatever they learn as a consequence of interacting with other people in this network using these resources.

So I've described a process, and again it's one of these things where there are four easy steps: aggregate, remix, repurpose, feed forward. So this is the process that we recommend to people – nothing is required in one of these courses, but this is what we recommend as the four major steps of working with the resources. You gather the resources, you remix them, join them together, mash them up, repurpose them, localize them, adapt them, mark them up, tag them, review them, lipdub them, do whatever with them, and then send them forward, communicate them to other people in the network.

That's where we stand now with open educational resources and open learning. And there's a whole world ahead. Our capacity for languages has greatly expanded in the last 20 years and in the next 20 years is going to expand again. We haven't even touched in a serious way on the internet the whole idea of Big Data, the Web of Data, sensor networks. We may have two billion people online. Imagine adding to the internet 20 billion sensors, machines, and other things that can send signals.

There's the whole way of representing information from the semantic web – RSS, geography, Friend-of-a-Friend, so on, a whole open learning ecosystem and not just a smallish network, still waiting to be grown. People are using more and more complex 'words' in this new language and we're finding that we don't need the publishers, we don't even need the academics in many cases, to create these resources.

And insofar as the academics and the publishers create these resources in the old linear static linguistic traditional manner they're speaking at cross-purposes in any case to the new form of learning that's happening now. The idea of using these resources to learn has as much to do with creating these resources as consuming these resources and it's in the creation of these resources that we acquire the greater capacities and skills that we need in order to function in this environment.