Half an Hour,

Mar 27, 2016

Look at this picture:

Did you see a cat? Or did you see my cat Alex? This is a question of some significance, since one of them exists and the other doesn't. And therein lie some important lessons in theory and theorizing.

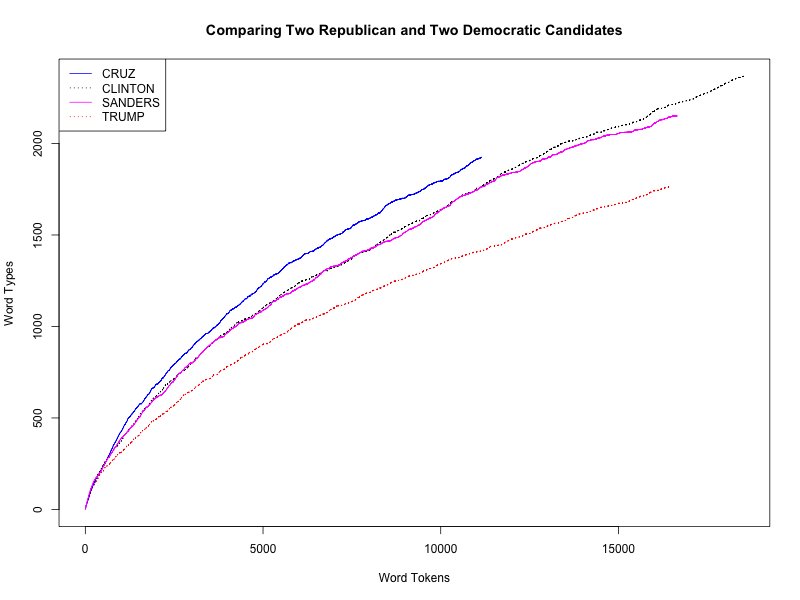

This post was prompted by a post on Language Log describing the speaking styles of the current presidential candidates. It's a simple comparison, graphing the candidates' word use by tokens and types, as follows:

To count tokens, you simply add +1 to the count each time the candidate utters a word. To count types, you add +1 to the count each time the candidate utters a new word. So, for example, if Berie Sanders says,

A sparrow has landed. This sparrow is a sign.

then Sanders has uttered nine (9) word tokens, but seven (7) word types (because the words 'sparrow' and 'a' are each repeated twice).

A token is an instance of a thing. A type is, well, a type of thing.

This is pretty important because almost all of our scientific reasoning in education (and just about everything else) is about types, not tokens. Scientific theories don't tell me about my can Alex, it tells me about cats. As in "cats will take possession of new objects in the house," and things like that.

The problem is, as I suggested above, types don't exist. There is nothing that exists in a type over and above the individual instances of that type. And if only statements about things that exist are true, then statements about types are literally not true.

These are not new issues; in fact they're very old. You've probably heard about Ockham's Razor. The actual and original statement of Ockham's razor is:

Do not multiply entities beyond necessity.

In other words, if you have a bird in the house, you have only one entity, this bird, and not two entities, this bird and a bird.

What does this mean? Well, technically, it means that we have to treat a type as a set, so that the type 'bird' equals the set of {'this bird', 'this bird', 'this bird', etc...}, and the word type 'sparrow' ={sparrow,sparrow) and so on. A set is a mathematical entity, and doesn't have to exist in the world to be useful. And 'truth' can be redefined as "true over the set of 'sparrows'", or some such thing. So we're good.

But we have to be careful. Just what is a type? Sure, it's a mathematical entity. But when we say "this is a type," what do we mean by that? To make a long story short: a type is something we make up. We decide what counts as a type. Because types don't actually exist, so there's nothing in the word that defines a type or distinguishes one type from another.

(This view is called nominalism. The view that opposes this conclusion is called essentialism, and is the idea that things have inherent 'essential' natures. A lot of naturalism is based on essentialism. For example, if someone says "Man's essential nature is to be at war," they are asserting that there is something in nature that is 'man' and that it is definable as 'has the nature of being at war'. Saul Kripke is a prominent proponent of essentialism).

Let me give you an example. Let's add another sentence the speech by Bernie Sanders:

A sparrow has landed. This sparrow is a sign. Landing is a sign.

Now we have 13 tokens; no dispute about that. (Right?) But how many types do we have? At first blush, we want to say there are seven (7) word types in the sentence, that is, that Sanders used seven different words.

types = {a,sparrow,has,landed,this,is,landing}

But did he? Maybe 'landed' and 'landing' are actually the same word. After all, they describe the same event. They are merely different forms of the verb 'to land'. If I say "I land" and "Paul lands" we are not saying different things about I and Paul.

Sure, you could say that the actual sequence of letters is what matters, so that if I use different letters, then I am using different word types, and if I use the same letters, then I am using the same word type. But let's add another sentence to Barry Sanders's speech:

A sparrow has landed. This sparrow is a sign. Landing is a sign. And I will sign my support.

So now Sanders has used the word 'sign' twice. It's the same sequence of letters, but is it the same word? One is a noun, a 'sign', which is a thing that stands for something else. The other is a verb, a form of the verb 'to sign', which means to put one's mark on paper. Sure, they're related. But are they the same word? Argubly they are not; they just happen to be spelled the same way.

What counts as a 'cat'? What counts as the word 'landed'? What counts as a 'millennial'? As a 'learner'? As a 'student'? Our theories about language, learning, and the world in general are all based on types, but a type is something we make up. Indeed, even the concept of a type is something we made up.

Naming things, counting things, generalizing over things - these are really useful tools we have created for ourselves in language and in thought to make the world easier to navigate (and, sometimes, to rationalize after the fact why we navigated on one way rather than another).

This is where the 'construction' in constructivism comes from. The actual act of learning, in constructivism, is the act of counting, naming, and associating things into types.The reason there are dozens and dozens of different theories under the heading of 'constructivism' is that there are many ways to construct something.

And this is what is meant - literally - by 'making meaning'. When we learn to use a word like 'cat', what we are learning is the name and nature of the set of things 'cat' stands for. Creating this set and populating it with entities is, literally, making meaning. And it is over this set of entities that we will draw inferences, make conclusions, and determine truth and falsehood.

This is also why constructivism is so hard to criticize. There are many different ways to make meaning. If you show that one way of making meaning is inadequate, then the constructivist always has another one to show you. After all, the theory (mostly) isn't about some specific way of making meaning. It's about the idea that 'to learn' is 'to make meaning', and these can be made in different ways.