Half an Hour,

Oct 31, 2020

This is an edited text transcript from my presentation from April 27, 2020.

Presentation page (audio, video, slides): https://www.downes.ca/presentation/520

This talk is about change. It's about the change we see individually in our homes and in our workplaces and it's about the larger changes sweeping through society. It's also about technology, where we think of technology in its broadest sense. It's about information, computation, automation, analytics, and it sets these against the broader milieu of social and cultural change where we're afforded both the chance to redesign our system of education from the ground up and the need to preserve what is important and valuable and desirable in the system we already have.

Hi. I'm Stephen Downes I'm a specialist in online learning technology, I'm based in Ottawa Canada and I'm happy to be here with you today. Join me as we go through a look at the change that has been happening and will be happening in our educational system today and into the future.

We think of change is something that happens only gradually and imperceptibly in society, but change often happens to individuals subtly, suddenly and without warning. It's as though we wake up one morning and we find that the world we once knew has disappeared even while other people proceed with their lives as usual as though nothing had happened. We get lulled into the sense of complacency about change: it'll be cyclical, it'll be seasonal, everything will come back to the way it was. And then one day everything changes, we've gone through obviously a major crisis in our society, and suddenly we're in the position where traditional learning isn't going to work and we have to move online.

It's the sort of thing that nobody could have predicted precisely but it's also the sort of thing that we should have and could have seen coming. Now I've written a number of times in the past that educational providers would one day face an overnight crisis that was 20 years in the making, and now it is here. This is the point at which traditional education has failed. It has failed through no fault of its own, it has failed because of the pandemic, but now we're going to see what parts of the educational system were working, what parts of the educational system were essential, and we can begin thinking about what we want when we go back to something like a normal education system.

You know when we're predicting the future (and some people say you can't predict the future but I think you can) I think one way of predicting the future is to look at what's unsustainable in society and instead of predicting how it will be sustained, to predict what will happen when it stops. So what's unsustainable?

- Our consumption of resources - especially building and transportation.

- Centralized hubs - a hub-and-spoke society that doesn't provide adequate safeguards for the massive spread of infection or even the massive spread of unhealthy ideas.

- Inequality - the method by which all of the wealth in our society is gradually being transferred into the hands of few people

A lot of what we do is dedicated toward sustaining these unsustainable things, but we need to be asking what happens when these unsustainable things stop happening. The unsustainable though is only a driver of change. There are other factors as well as well as the driver of change. There's the attractor of change. A driver doesn't push change in any specific direction, it just pushes change. A pandemic doesn't force us to go online. We could have done many other things: we could have shut down the system entirely, for example. Events cause crises and all of these things. Inventions and growth cause change but they don't push it in a specific direction.

The direction of change is based on the attractors. The attractors are the values, goals, desires and needs that we all have. Audrey Watters commented recently (I don't agree at all) about the famous saying by computer scientist Alan Kay that the best way to predict the future is to build it. She's argued elsewhere she writes that the best way to predict the future is to issue a press release. The best way to predict the future is to get Thomas Friedman to write an op-ed in the New York Times about your idea and then a bunch of college administrators will likely believe that it's inevitable. And she has a point, right? She has a point in that whoever sets these values goals desires and needs these are also the people who are setting what our changes will be in society.

I think that we at least should and maybe do create the future of change through our own individual actions. The future of learning is not simply an extension of the past, it's not simply going to go back to the way it was. How we react, how we build and develop through this crisis and beyond will create the future of education. Every day the future is created anew it weaves and warps and whines through many variations of change. The future is complex, it is challenging, and if we want it to be it doesn't have to be dystopian. It can be amazing but we have to make it that way.

---

Now in business they often talk about something called a 'value proposition'. The value proposition is an easy-to-understand reason why a customer should buy a product or service. It is a statement that tells us how whatever it is we're building fills a need. What is the benefit to the person who uses or buys or pays for that thing? It's a useful concept because it's a way of capturing this idea of goals, values, desires, objectives, etc.

So what is a value proposition of Education? Well, it's not exactly what we have now. Gerry Robinson in Schools Week recently wrote, "We don't want it to go back to normal." Normal wasn't working. And why not? And how do we get to something better? He continued, the message in one deprived school district is "we're all in this together and everyone needs to play their part", and he writes, "how deeply insulting to suggest that this has ever been the case. Our children have long lived with pre-existing conditions of staggering deprivation," and I think that our focus on both relief and reconstruction needs to start not at the top, not at the people who are doing well and benefiting off our unsustainable mechanisms in society, but the people who are at the bottom, making sure that those most in need have housing, food, health care, clothing, education, connectivity, a voice. And I think that in itself is going to be a sufficient challenge for both the economy and morality of our times.

So what are the priorities in a school system? Well in a recent report from McKinsey the authors argue there are four priorities: maintaining health and safety of students, staff and the community; maximizing student learning; thriving supporting teachers and staff; and establishing a sound operational financial foundation. Well the last one is just to make the first three work. Supporting and teachers and staff: that might be an objective of a school system, but it isn't necessarily the objective people paying for the school system, right? I mean, we all want people to have jobs, but the reason why we pay for a school system isn't simply to employ teachers. No, it's the first two, really. It's maintaining health and safety of students and it's maximizing student learning and thriving. And maybe it's the second part even of that second statement, 'maximizing student thriving'. Even so, say the McKinsey authors, we believe that the issues regarding equity, that is, ensuring the needs and the most vulnerable are met, should be front and center both during the closure and after schools after students return to schools. And that would be a substantial change, wouldn't it.

What is the value proposition of the school or of a teacher or of a university? How much of it is entangled in sustaining the unsustainable? Look at schools. A big objection to continuing with online learning, or as they're calling it today, 'remote teaching', is the fact that if students are at home, especially young students, parents have to take care of them. And what are parents going to do if both parents in the home are working, as more and more people have to do these days?

Another argument is that schools are essential for socialization. This is why people should be together, preparing for work. But what work what will be? The future of work in our changing society (as I've talked about, especially in the elite institutions) it's not about any of these things, it's just about creating a network of contacts so that well established people can get in touch with other well established people and work together to produce their wealth or to preserve their wealth and their privilege. You know a lot of this is unsustainable when Steve Krause talks about what the purpose of an elite education is, and you know this is true, from private schools all the way up through Ivy League or Oxbridge universities. Now taking class, he says, is not what it's all about. It's also the whole lifestyle of dorms or near-campus apartments, sporting events, frats, sororities, parties, beautiful buildings, campuses, etc., and he says (contentiously but I don't disagree) elite universities don't like online classes because they are not the college experience, and they still believe online classes are for poor people.

And that creates a challenge, doesn't it? It creates a challenge for what we will fund during this crisis and what we will fund going forward, because ultimately and especially in a period of a fiscal crisis, higher education institutions are going to need government support, and government support is not going to include sporting events, frats and sororities, clubs, parties, beautiful buildings, and campuses. At a certain point people are going to realize that the problems of equity exists not so much in online learning as they do in the higher education system in general, so we're going to need to re-examine what we as a society want to support in our educational system, and it may not be the unsustainable model of the past.

The other factor of the big shift to online learning is technology. Now we think of technology really as, you know, tools and gadgets, things like our phones and earphones and, you know, stuff like that, computers, internet, all of that; but really technology should be thought of as just another word for environment. Technology as environment, environment as technology. Because everywhere and in every place that we exist we are working with this environment, we are modifying this environment, and then McLuhan would say, this environment modifies us. Whether we are working in a place with limited electricity, books and no internet, or whether we are working in a place with fiber optics, high-end computers, and virtual reality, it's a technology.

And, you know, we can say that technology is good, technology is bad, but as we all know it depends on how we use technology. So what are we going to say about technology? Well, the limits of technology define the limits of what we can do, and that is true for all technologies. Our clothing defines where we can go, our food production system defines how many people we can support, and so on. We can't teleport anything larger than a photon, we can't implant knowledge directly into a human head, we can't create energy and resources out of nothing. So technology creates our limits, and these limits are currently unequally distributed. A certain number of people have a lot of technology and are able to do a great deal of things with it. Other people have less access to technology and they're more limited.

We need to negotiate a social contract with ourselves with each other and with technology and we're going to need to rebuild that that contract describing what we can do, what we think everybody should be able to do, and as well some of the things that we think nobody should be able to do. I mean, this is one of the major criticisms of the Silicon Valley ethos, right? The Silicon Valley ethos is "move fast break things". Well, it turns out we don't want people to break things. Breaking things creates social problems. We want to move fast, maybe, although you know there's that resistance to change and we want to move only as fast as we're capable of. So we need to come to some kind of understanding of how we shape technology and how technology shapes us. And this isn't a technological problem, is it? It's a social problem.

You know, hundreds now are predicting the future of online learning in 2020 and beyond. What will it look like? And Clive Shepard gives us a perspective: think about how we watch music drama or sport today. If we wanted to do it all by face-to-face, well, as he says unless you're rich and with considerable discretionary time it would be completely impractical. And yet we think all of our learning should be a lot of face to face. Now everybody (well, not everybody, but you know…) agrees, kids will go back to brick-and-mortar schools. But the act of sending our kids every morning to a place called a school, there's a cultural habit formed over many generations. Well that's true, but so is employment, and look what happened to that. So is going to a football game, look what happened to that.

Some people say that our technological environment just doesn't support what we need at school. Alex Usher says for example, your predictions that all learning will go online our nonsense, he says education is social and online learning isn't set up for that. But I think that we're seeing in this pandemic that, well, first of all, yes, it is set up for that. Online learning is social, or can be social, our community bees can form online, and we've known that for twenty years. And secondly, as I said, the voters at some point will tire of paying for social clubs for rich people while doing nothing for people who can't afford it. We need to renegotiate learning the way we've renegotiated art and music and sports and the rest. Remember, music used to be something only rich people could have, now not everybody can go to a musical show, but we can all go sometimes, and we have the benefit of being able to listen to music at any time in any place that we want.

What is it that we want to set up in the future? In China they approach this challenge of the pandemic by designing a blend of synchronous and asynchronous teaching that is live or static and they identified four essential technologically enabled pedagogical techniques that should be used:

- · live streaming teaching, you know, like the live interactive kind of thing;

- · online real-time interactive teaching;

- · online self-regulated learning with real-time interactive question-and-answer; and

- · online cooperative learning guided by teachers.

You see how it's this mix, it's this blend, right? A lot of people have touted the benefits of blended learning. I've always been a bit of a skeptic because, you know, blended learning means you need to be in some place at some time, but if you don't have to be all together in a specific place on a specific time, then you can make this blend work. And we can have learning in person for special occasions, like labs or distinguished lectures or whatever, and a lot of the rest of it can be offline, and this is a way of renegotiating our interaction with technology so that we can all have some of the benefits that currently only the rich people have.

---

The next thing about technology is affordances. Because when change happens, really, it's not about the particular nature of the change ever that matters. It doesn't matter whether it's a pandemic or a nuclear war or alien invasion, right? What matters is how it changes what we can do that we couldn't do before and sometimes (we're certainly feeling that now) what we can't do that we used to be able to do. So what can we do that we couldn't do before? Well I've always said (and I'm not the only one to have said this) that new technologies that will be important in the future will be those that help us create new things in new ways. I'm thinking 'new things' very broadly, right? Music, art, literature, communications, networks, software, gadgets, you know, think of the people with their 3d printers printing for a dollar each valves that used to sell for $10,000. You can't go back to the way it was after you do that. As much as the company would like to preserve it, you can't.

The idea of an affordance is that it's something you can do with a tool that you couldn't do before. We say that the tool 'affords' this opportunity. And it's important to keep in mind the affordances are not just the things that the tool was designed to enable but also the novel uses people come up with in the process of using the tool. I like to talk about how we've taken this international research and communications network that we spent trillions of dollars on and we use it to send cat pictures, and we need to understand that the sending of cat pictures is an instantiation or a presentation of our values, our needs, our goals, and our ambitions. We send cat pictures because we like cats, they matter to us (dogs too, but lesser so) and our use of this technology in this way in some way shapes what technology looks like. Think of the whole phenomenon of what they call 'LOLcats' (using pictures of cats with text to create wry sarcastic messages) and using these as a way of communicating, and then gradually visual communication evolving to emojis and Tik-Tok and all of the rest, right?

What we value really does shape technology, you know. And there's a similar concept in education (maybe you will be familiar with it) and that's the zone of proximal development defined by Vygotsky, as the distance between the actual developmental level is determined by independent problem-solving and the level of potential development as determined through problem-solving under adult guidance or in collaboration with more capable peers. So education and Technology both have affordances, education and technology are both about helping us do what we weren't able to do before, and sometimes (and this isn't explicit in the zone of proximal development, but it's implicit) sometimes education and technology are both implicit in taking away our ability to do some things that we could before. Now in polite society we call this 'socialization' and that is sometimes just as important as what we can do, the new things that we can do.

Well I like to think of technology as a language, just as I like to think of education as a language, just as I like to think of LOLcats and, you know, the artifacts that we create with technologies as a language, or technological interface as a language. Interface design is the science of that language and it's important to understand it this way, I think, because no individual will define the grammar and the semantics of this new language, but we're all going to need to learn to learn this new literacy to both understand what technology and education and the rest are trying to do, and also to express ourselves through whatever interfaces we have available, and ultimately this language, these interfaces, these technologies will be used, and this use defines meaning and shapes cognition.

George Siemens, I think, captures this nicely he says, "Consider our curriculum as a self-contained coherent resource," writes Siemens. "The goal of education? Teach this container to the students. What happens when you add artifact creation? If someone comes along and says, 'what about the power structure and the bias that underpins this content,'? Bam. It's a new course. Someone creates a video reacting to a lecture I delivered? Bam. It's a new course." It's not the simple fact of being virtual or non-virtual that makes it better. It's the element of adding creativity to the curriculum, and to the extent this is enabled by virtual media, virtual media are better. It's about affordances, it's about having our educational system and our technology enable us to create, and for this creativity to take us forward into whatever new society, changed society, we want to support.

---

Yeah, the future of virtual learning is so often depicted in terms of the distribution of learning resources… "oh, we got to get this course online." I think that's a mistake. The technologies of virtual learning online learning (all right, dare I say, 'remote teaching') will be the technologies that help us create new things in new ways so let's think about this for a bit. Let's think about normal education - what is normal education, what is changing, and what is going to continue to change?

Marshall McLuhan famously said that there's a tetrad of media effects when contemplating a newer emergent medium. What does it enhance, what does it make obsolete, what does it retrieve, what does it become when it's pushed to its limit? Well I think we're seeing elements of all of that in education as it's being changed involuntarily through the through the pandemic, right? What does it enhance? I think it enhances asynchronous communication, I think it enhances creativity, I think it enhances perhaps a certain leveling of communications capacity (in the classroom, the extrovert was always the person who carried the day; online it's not necessarily that). What does it make obsolete, well, that's a good question. Bonnie Stuart might say grades, right? Or playgrounds? What does it retrieve, what is the thing that it brings back? A lot of people say the oral culture, storytelling, things like that. I'm not so sure. What does it become when it's pushed to its limit? Cat pictures.

I think the way to understand normal education is to ask why are we doing it this way. Why do we offer normal education normally at all, particularly now that we have this alternative and these affordances? So why are we offering courses in classrooms to cohorts? And when we move online, the question becomes, why are we offering online courses in virtual classrooms to virtual courts? Some good questions.

Let's look at classrooms. You know I think that in time our online classrooms will begin to look less and less like classrooms. There's this model of change, right? SAMR. Substitution, Augmentation, Modification, Replacement. I think we're in that process now, and I think that more and more in the future our synchronous instructional environments will begin to look like our collaborative work environments. You know, I work in my day job as a researcher in a national science lab and the tools I have, our productivity suites ,integrated development environments, some virtualization communications tools (Slack for example), some specialized interfaces some of my colleagues who are working in analytics use, applications that allow them to do analytics on a computer screen; and that is what's going to replace the kind of learning we have where, you know, people sitting in rows or sitting around tables or whatever, and focusing on what a teacher is saying or even focusing on what each other is saying, this this doesn't go away completely (just before doing this video we had an online team meeting and we did our reports and all of that it seems sort of silly to drive all the way into Ottawa now just to do that we just did it online) so you know there will be still some of that, but a lot of it will be working with the tools and the online environments that characterize our jobs, and you sort of wonder why the rest of us can't have this you look at what MIT does with Media Lab. Media Lab is this big amazing collection of tools and devices. You know, they had 3d printers before the rest of us, etc and they make all kinds of neat things and MIT issues a press release about it. Look at what Stanford does with the incubators programs. Look at what Waterloo engineering students do with teams devoted to rocketry or robotics or alternative tools. Why can't the rest of us have it? Why can't we have our education like this instead of 'we have to listen to the content'?

What about cohorts? Why are there cohorts at all? I'll tell you, at least to one degree the reason why a person wants to study at MIT or Yale or Oxford isn't the quality of the instruction, you know. I've looked at their course outlines and the course outline so I got in philosophy at the University of Calgary, and it's virtually the same document, and the teachers were just as capable as each other, but what was different about me and Calgary and somebody at say Harvard is the person sitting next to them, right, and you know sometimes we could say you know it's the quality of the person sitting next to them in class, or another way of saying this a bit more cynically is you've accomplished your goal in a Harvard education by getting into Harvard, and then it doesn't matter if you drop out after or not you've been 'Harvard educated' and you've developed the social network (in some cases quite literally) of contacts that you can use for the rest of your life. This is the benefit, the purpose at the heart of Harvard education. Why aren't we replicating that in the education for the rest of us? We're not getting that benefit.

And think about the changes that are coming to the education the rest of us are getting. There are big changes being planned to move away from the cohort model. And you know, it's a statement under the guise of "we're going to move away from grades", "we're going to move away from class time". That's fair enough, and I get that, but they're moving toward competency-based education. Competency-based education generally done individually, and certainly done without a cohort, where the value of your education is going to be measured in these specific skills that you can achieve. It doesn't matter how you got them, and it sounds like it's fair and it's democratic and all of that.

But the big advantage that people who are able to have in developing these cohorts in the networks of people who will support them for the rest of their career disappears in this kind of education. It is because we want to hang on to this benefit that new environments dedicated to new models of cohort formation are likely in the future, probably the short-term future, and a big part of the success of Zoom is explained by the fact that Zoom allows us to connect almost instantly, Zoom allows us to keep our social connections together when for one reason or another we weren't able to keep them together by any other mechanism after physical school stopped. These will these new models will be the far more significant outcome of our rethinking of cohorts but right now they're all been obscured by the loud debate over personalized learning and competency-based curriculum. Cohort formation is going to be key, and if we get that right we get online learning right.

Pedagogy. This is a tricky one. Our idea of pedagogy recently has been replaced, certainly in online learning, and more and more in traditional learning, by an understanding of pedagogy as instructional design. And instructional design as it has developed over the last two decades has become this underlying "science of online learning" (in quotation marks) and the discipline of an instructional designer has been recast as a professional.

Now we can't go back to the days where our understanding of learning was limited by the conception of a teacher managing the collection of students in the classroom. Pedagogy can't be that anymore. Pedagogy has to include some of this new stuff. The practice and the art of pedagogy has been replaced to a certain degree by technology and a science, and so we seek in vain to return to that former understanding, but moving forward we need to try to identify those core values that existed in pedagogy as originally conceived and maybe being lost in this development of this science and profession of instructional design, or dare I say, "learning engineering".

What did it matter what a teacher did? What were the outcomes that we hoped for? How does our current understanding of instructional design meet these, if at all? How can we develop in the future to address these things? Well I'm not going to have some quick and happy answers here, but I do know you know you look at all the literature of care and presence, and all of that has surfaced recently. We will will come back to that in a bit. And we see that there is something missing in this science of instructional design and programmed learning and competency-based education that isn't solved simply by smarter robots - but what is it?

---

You know, I want to get at what it is we're even up to when we're doing this whole thing about educating anyways. And I think that, you know, we have this idea that education is the inculcation of skills and knowledge. Rod Savoie used to say you know getting people from point K0 to Kn where K is knowledge and there's this knowledge gap that we're trying to get over. And I don't think that's it at all. I don't think that we're trying to develop knowledge in an educational system. I think that we're trying to develop perception and recognition and I think that this is how we learn. We develop and we grow in our more adult professional lives and that the purpose of an education should be to move us toward that capacity.

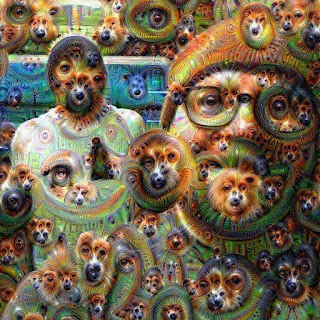

Well, let me explain a little bit about what I mean. If you stare into chaos like static on a TV or whatever you begin to see things. I'm living a house here with a wooden roof. I'm going to show this to you. There's my wooden roof. Now when I lie in bed (sorry about the camera jitter, I wanted you to see that) when I lie in bed I stare up at that wooden roof and all I see are dogs, pictures of dogs, because the it's knotty pine, right, so two eyes and a snout – dog.

I'm just like those computer systems where you feed them a picture of whatever and get dog dog dog dog dog, right?

So what's happening here? When you look at anything patterns begin to emerge. These patterns form and reform as the chaos folds and unfolds, and we see this everywhere. No one would really say that Orion is really there drawing his bow in the heavens and the stars, but we see him. No Great Bear really circumnavigates the pole each year, but we see him we see him clearly, and yet these constellations are as static and as real as you and I. So what we're talking about here is the idea that patterns arise out of complex phenomena, not just some complex phenomena, all complex phenomena.

And they don't just arise all by their lonesome, right? It's not like Orion is really there. It's a two-way street. The patterns emerge out of this more basic media, but there has to be somewhere someone to see the pattern. It doesn't get to be a pattern until there's a perceiver of the pattern. Otherwise it's just chaos and noise, right? So you can have a cloud, but you have to have a person looking at the cloud to see a fluffy bunny in the cloud. You can have stars but you have to have a person looking at the stars to see Orion in the stars. And now we've developed this interaction between ourselves and our environment. In this way, when the environment moves the patterns move. If we see a storm front coming through our clouds change shape and our fluffy bunny changes into something more ominous, and it's not a thing that's approaching it's just our perception of what's there changing.

So this is how we should think of learning. What we're trying to do is to develop people in such a way that they perceive patterns in phenomena usefully. And the 'usefully' bit is really important here, right? And the 'perceived' bit is really important here. To perceive a pattern you need to be organized in a certain way. You yourself need to be a network on your own, a network that when presented with phenomena responds in a characteristic way, just like you react "Oh hi!" when you see your grandmother coming through the train station, and that way needs to be in a way that serves you, serves your goals, your needs, your values, etc.

So what does all that have to do with education? Well again, we focus so much on the content of education, the curriculum, the competencies, the skills, but we should see all of that really as substrate. The idea here from that should emerge from this short (ultra short) description is this idea of a galaxy of resources, a massive complex ecosystem of people, devices, websites, resources, content services, and all the changes that emerge from this ecosystem, all these massive system-wide changes we need to develop the capacity to recognize these, and recognize them when viewed at some distance, so that they don't overwhelm us. Well that's a little bit hand-wavy, I know it's hand-wavy, but there are practical examples that abound.

I was listening just yesterday to people, to researchers, talking about the pandemic and talking about how science is done in trying to find, you know, first of all trying to detect epidemics in the first place and then trying to develop a response and I was only sort of half listening (I'll be honest) but the person said "the way we work we look for patterns and it's the pattern and that tells us there's an epidemic, it's the pattern that tells us what kind of epidemic, it is etc.," and I went, yeah, exactly, that's what science is, it's pattern recognition, that's what knowledge is, it's pattern recognition.

And the way you get pattern recognition is experience in an environment, and so it should be this environment that we're thinking about in the development of education, not the content, not the curriculum. We should be asking, what kind of environments are we building for our students when they're at home?

You know, a lot of this is all based around the idea of communication. I've put 'conferencing' (on the slide) and 'communication'. 'Conferencing' isn't so much the thing. Using zoom is conferencing, but really we're interested in communication. We've gone through different dimensions of thinking about what this means over the last 20 years. The first the early framework focused so much on granularity: what size messages are we sending? People focused on whether we were having synchronous conversations or asynchronous conversations. We also focused a lot on privacy and confidentiality. Should we be locking down our systems? And the types of media that we were using: were they online courses? The images: were they graphics, were they simulations alone?

A lot of this was just focused on, if you will, the physical substrate of communication, and we needed to do that because we were defining a new environment, but over time we got a set of new definitions, the social networks emerged and we began to see communication in a more sophisticated light. Now things like context became important. Can collaboration and communication occur? Who is part of our communication network? Can robots be part of our communications network, is that acceptable?

---

Platform. We develop platform after platform, and each time we built a platform, a new communication regime would form on that platform, almost by itself. You know, I mean, Zuckerberg built Facebook but the users of Facebook built the communication platform that uses it. Google built Google+, nobody used it, no communications. Today we're seeing things like Instagram and Tik-Tok and the rest, and again we're getting new communications environments. Animal Crossing.

This is one of the least defined dimensions of communication, and probably the one with the most potential for information or for innovation. We're looking at collaboration and communications tools now, moving away from business management software development and into the home to provide everything from counseling to support student advice medical information, and yes, learning. But now we're moving beyond that beyond those dimensions of communication to a more meta level. I think I put it under the heading of interactivity and presence and these are the things that are important now. These have to do with, if you will, the intention of communicating. Why are we communicating, what are we trying to get out of communication?

For example: the structure of communication. We're moving from linear to multi-dimensional. I'm watching Westworld because I remember watching Westworld in the Rialto in Ottawa. The original with Yul Brenner had a permanent impact on me, but the new Westworld is brilliant because it messes around with linear and multi-dimensionality in that, for a robot, remembering something is just the same as living something. And so we're moving around in time and in dimension a lot, and I like that, but it becomes less and less like telling a story more and more like painting a picture. Dialog is shifting from text to multimedia, from words to emojis, from narratives to performance. We're communicating with a much richer toolset, and we're expressing much more sophisticated and in many ways ineffable messages.

And then, autonomy. We're shifting from a demand-driven economy to a needs-driven economy. What I mean by that is it's less about what the education system demands of us in order say to qualify for a credential, and more about how an education system responds to our needs, and so things like care and agency coming to the fore. Where we were satisfying the demands of the education system, care and agency didn't matter, but now where education is trying to address personal and social goals, care and agency matter.

---

So where do we go from here? I think that many of our unsustainable things are beginning to stop. The epidemic is just one thing, but you know, I mean there are going to be some other wheels that stop turning. Our dependence on fossil fuels, for example. Our capacity to just simply keep building using cement without stop. Our consumption of the resources of the world, fish for example. These alternatives are becoming unsustainable, and when they do all of our options kind of collapse into a single point, and we have to make decisions. As Caesar says, "the die is cast." Some of these decisions, once we make them, we can't unmake them, and I'm thinking a lot of these centralized systems are going to collapse into themselves. I'm not just thinking about large data centers or even massive centers of saying media and commerce, but I'm thinking as well that many of the large companies that operate them and the enormous economies that sustain them are kind of running their course, and hopefully they don't take the rest of us down with them. They might, you know.

If a university system collapses, and I'm not saying it'll collapse as a result of this pandemic, but if it collapses suddenly it takes a lot of people down with it and that's not a good thing. But if it's collapsing we need to be thinking about how can we gentle that collapse, if you will, and I think we need to be thinking about how we're going to make this work, and overall what that means is, how do we make this shift work from a centralized system to a decentralized system, a shift from large centers of learning and educational power like Harvard and Yale and MIT (who would like to continue to be the ones that set the standard for everyone)? Now, how do we move to something more distributed and decentralized so that everybody can have the advantage that currently accrues only to Harvard and Yale students?

---

Goldie Blumenstyk, who writes for The Chronicle of Higher Education, came forward with a number of interesting and I thought quite useful suggestions. She said, for example, we should be looking at a more interdisciplinary approach to teaching with more community-based internships and practicums. This is practical because it helps develop this recognition that we need in order to work on a day to day basis. We can learn how to adapt to changing and unpredictable circumstances while working in the community, while working on their practicum, but also as we do this we're developing our personal networks of contacts, the people that we communicate with, the people that we transmit our values to and who in turn transmit their values to us, so we get it from people working in the community as opposed to from an anonymous and possibly uninformed authority from a large centralized source.

She also suggests more applied learning that can be evaluated through guided reflection and mentoring, as opposed to tests and quizzes which don't really evaluate anything, to prepare students in all fields for careers of purpose for society. The distinction here, right, the distinction is between knowledge as acquiring something and passing the task and doing what's demanded of us, and education as creating agency. But not self-serving agency, that's one of these unsustainable things. But agency of service and support for society.

And third, she suggests customized education leveraging the online environment and technology tools, (education) that is both values based and experiential. We're talking a little bit about values in a couple minutes, but the idea here is it's not customized in the sense that we're getting a production line model with racing stripes, it's customized (in my view anyways) based on the environment, the technology, the purpose and the outcome we choose. Now we choose these things and we customize our education by making it, by creating it for ourselves. Now what she's suggesting is a very different role for an education system from that we have today. I think it's a pretty good starting point and it would go a long way toward making higher education not this thing that preserves the privilege of rich people but this thing that helps each and all of us develop grow and help making our society and our community a better place, and that's where education ultimately probably should be.

You know there's a lot of technology that is being developed and deployed in education today, and as I commented two years ago, compared with the range of possibilities and ambitions realizable in education how tame these ambitions are of discourse analysis and predictive modeling. You know, it's as though best the conception of things like learning analytics and program management and all the rest can do nothing more thanks to support and enhance the traditional model: courses, classes, cohorts, remember stuff, pass the test, get a career. But any of these systems, any kind of adaptive learning, any kind of education system is going to be teleological, it is going to be goal directed, it's going to define certain outcomes that the system is intended to fulfill, and these outcomes define success and failure in that system.

And the question before us is, how are these outcomes defined? How did it become the case that learning is simply the acquisition of a skill or the remembering of some piece of knowledge, despite all the evidence that there is that it's not? You know you see on the slide, how does a master plumber solve a problem as compared to a novice? Experts don't just have more knowledge, they see things differently. How do we transform education into a way of seeing things differently, into enabling us to be perceivers and agents who are able to adapt to changing world, changing circumstances (including global pandemics) and to move forward in productive and meaningful directions?

A lot of people have been talking about the values that underlie education and recently the term of the week has been 'care' and also 'equity' and, you know, the big objection as we've been moving to online learning is we lose the equity, we lose the care, as though the traditional system demonstrated these. As if we have equity, as if we have care. If we want that care we have to go back to our kindergarten teacher, it's probably the last time we saw it.

Now why are people raising these things? I think, you know, some people are raising them because they want to think of learning design as a profession, and so you need a code of ethics and care and all of that, and others are expressing it because they're genuinely concerned about the unequal distribution of computer and Internet technology and the resulting inequality in online learning, and that's a valid concern, one that people aren't willing to address, but it's a valid concern. Or some people are raising them to return to a simpler time when education was a duty of care as expressed by a teacher to a student. That's looking back, but we can't go back, we can't reconvert our educational system to kindergarten for everyone.

The real question that I'm asking is, how do we define these today? How do we define what they are? How do we define what our fundamental values are in learning? How do we as a society learn how to educate? We go back to looking at the kind of society we want to have when the unsustainable fails, what does society look like once our consumption of resources can no longer support a society based on materialism and material wealth, what do we want to have when our hub-and-spoke society that depends on centralization, authoritative media management, managerialism, capitalism - when that doesn't provide adequate safeguards against not only viruses but, you know, fake news, populism – pick your poison if you will.

What does society look like when we've addressed finally the actual real questions? I mean inequality and inequity, not simply a lack of access to a computer system, but a lack of access to anything? How does our society work when we're not creating institutions designed to support the continuing aggregation of wealth by rich people? This is a very different system, we have to be frank about that. There's not going to be a common statement of principles that defines all of it for us. I'd like there to be one, I really would, but there's not going to be. We're each of us individually going to have to wrestle with these questions, wrestle with them for ourselves, and we have to each of us define what our own values, purposes, objectives, and goals are, and sometimes they will be for ourselves, sometimes they will be for others, sometimes they will be for society as a whole.

That's up to us and we need to then take it into our own hands to pass these things on, you know, and ultimately that's why creation is such an important part of education. Because if you can't create, if you can't write, if you can't speak, if you can't produce a video, like this then you can't pass on your own values beliefs, etc., and then they become by default whoever created the technology - the government, whatever, right?

So we need to think about these things that matter to us, and then we need to pass them on, and I think we need first to pass them along to those who are closest to us, but then pass to them on - well frankly anyone who will listen. And that's why I'm recording this video today. Because I want to pass these things on.

That's what I have to say, that's my reaction to the pandemic. I think that it's showing some of the things that are unsustainable in society and forcing a lot of change on us that we didn't really want, but we got, and I think though also it's giving us some opportunities that we didn't know we had, and it's these opportunities that I want to focus on. Let's make this a more equitable society by focusing on those in need, let's make this a society with values and meaning and objectives and goals by defining these and then working toward these, and let's make them for all of us and not just a privileged few. If we can do that then we come out of this pandemic better than we went into it and that I think would be an accomplishment.

Thanks everyone, my name once again is Stephen Downes, so you can find me at my website https://www.downes.ca

Mentions

- Stephen's Web ~ The Future of Online Learning 2020 ~ Stephen Downes, Oct 31, 2020, - , Oct 31, 2020

, - , Oct 31, 2020

, - Value Proposition Definition, Oct 31, 2020

, - , Oct 31, 2020

, - School-system priorities in the age of coronavirus | McKinsey, Oct 31, 2020

, - The Elite “College Experience” is Not Compatible with Covid-19 – Steven D. Krause, Oct 31, 2020

, - Clive on Learning: Face-to-face is for special occasions - 2020 edition, Oct 31, 2020

, - Coronavirus (17, I think? Yes, 17) – The Future of Online Learning - HESA, Oct 31, 2020

, - , Oct 31, 2020

, - Coronavirus, a Brescia manca una valvola per i rianimatori: ingegneri e fisici la stampano in 3D in sei ore | Business Insider Italia, Oct 31, 2020

, - , Oct 31, 2020

, - , Oct 31, 2020

, - , Oct 31, 2020

, - , Oct 31, 2020

, - Westworld (TV Series 2016– ) - IMDb, Oct 31, 2020

, - Westworld (1973) - IMDb, Oct 31, 2020

, - The Higher Ed We Need Now, Oct 31, 2020

, - Stephen's Web ~ Page 152, Oct 31, 2020

, - The Future Of Online Learning 2020, Jan 02, 2021