Abstract

The study explores insights into the phenomenon of Australian lecturers’ lived experiences of teaching standalone critical thinking units within associate degree courses at one university in Victoria, Melbourne, Australia. The study makes an original contribution by focusing upon the experiences of teaching staff in Australian universities in relation to teaching critical thinking, particularly from a Heideggerian hermeneutic phenomenological and Gadamerian hermeneutic theoretical and conceptual framework. At present, there are no unified methods, frameworks, or models of teaching critical thinking in Australian higher education. This problem for lecturers is an important aspect of a university education that is not well understood. This is a global educational issue and is a matter of teaching and learning concern worldwide in tertiary education (e.g. United States of America, New Zealand, Canada, and the UK). Although, several studies have been conducted on teaching critical thinking from the perspective of university lecturers. There is limited research that focus on teaching staff in Australian universities’ experience with teaching critical thinking that has used Heidegger’s hermeneutic phenomenology and Gadamer’s hermeneutic circle, interpretive approach in gathering data. Using interviews, data is conducted with three first-year undergraduate Australian university Ph.D. lecturers. During the analysis of the empirical data, three themes were significant in revealing the key findings: (a) Dwelling; (b) Sorge, and (c) Concern. The comprehensive understanding of the results was that the challenges university lecturers faced in developing students to thinking critically provided new pedagogical curriculum insights for the teaching and learning of a standalone critical thinking unit within the associate degree course.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction and context of the study

The goal of Australian universities is to develop students to think critically, and lecturers are committed to teaching critical thinking (Go8, 2021; ACER 2019; AQF 2013). Critical thinking skills are a requisite skill that the Australian teaching staff must develop in their students for them to achieve the unit learning outcomes, which is a core criterion in the Australian Qualifications Framework (ACER 2019; AQF 2013; Go8, 2021; Heard et al., 2020). However, there are several significant ontologically and epistemically pedagogical questions in relation to teaching critical thinking that require cautious remedy if this goal is to be met satisfactorily within the Australian associate degree courses. The first problem to consider is what about critical thinking makes it an unsolved mystery in Australian higher education, which is directly associated with how the Australian teaching staff describe their lived experiences of critical thinking. The second problem is about pedagogy. Currently, there are no unified approaches or models of teaching critical thinking, which is closely connected to how the Australian teaching staff describe their lived experiences of teaching critical thinking. The significance of the first and the second problem for lecturers of such an important aspect of a university education is not well understood. These problems do not affect only Australian lecturers, but also other teaching staff around the world (e.g. United States of America, New Zealand, Canada, and the UK), who are teaching critical thinking in higher education (Danvers, 2015; Lai, 2011). For instance, given that critical thinking is conceptualized in various ways and there are different models and theories for defining critical thinking from the origin of philosophy, psychology, sociology, education, and its comprising attributes and associated activities, curriculum development is often faced by Anglophone universities globally. How to teach critical thinking successfully presents problems or phenomena affecting lecturers and students in higher education around the world, including but not limited to widespread social and economic issues. The importance of critical thinking goes beyond the Australian Qualifications Framework (AQF) and multinational corporations. Critical thinking is also essential for different Anglophone democratic nations. For example, how many tanks, battleships, and fighter planes do we need to stockpile to keep ourselves safe from potential threats? Where to best place our embassy? How much money should we spend on our military vs hospitals? Who should we choose as our next prime minister or president (Weinstein, 1991)? Should ChatGPT, Clowning, and AI be banned? In addition, how to combat misinformation or propaganda, which is a global threat that not only affects Australian higher education but also is a global threat that requires distinct types of critical thinking skills (Weinstein, 1991; AQF 2013).

There are diverse viewpoints or conflicting conceptualizations of critical thinking from the viewpoint of philosophy, psychology, sociology, and education (Danvers, 2015; Lai, 2011; Willingham, 2019). These differences in framework of critical thinking are observed in other countries or higher education systems in literature, and within a broader global framework of this research (Danvers, 2015; Heard et al., 2020). This study adopted a framework for researching critical thinking from a philosophical conceptual model of critical thinking which aligns with the study’s goals and hypotheses. This creates a clear link between the central research question and applies to the University X’s (2020) Graduate Capabilities and/or Outcomes. In 1990, the American Philosophical Associations conducted an empirical study determining critical thinking skills with the help of experts. They named it the Delphi report, and one of those experts was Peter Facione (1990). The Delphi report defined critical thinking as “self-regulatory judgment that gives reasoned consideration of evidence, contexts, conceptualizations, methods, and criteria, resulting in interpretation, analysis, evaluation, and inference (p. 2)”. This definition really emphasises the necessary skill that individual requires to become effective critical thinkers. Facione’s (1990) domain skill of Judgement, Analysis, Synthesis, and evaluation is also relevant and applicable within the Australian higher education domain which can be found in the Australian Quality Framework under Qualification Types (AQF, 2013 and ACER, 2019), and in University X’s (2020) Graduate Capabilities.

This initial part of this empirical research presents the introduction to the problem and the context of the study. My personal belief in the importance of critical thinking for individuals and societies was the core motivation for starting this research journey. My own struggles and lived experience with teaching critical thinking in Australia, People’s Republic of China, and the United Arab Emirates informed my position on the subject. I believe that the public rarely understands what it is truly like to teach critical thinking as a twenty-first-century skill. I provide reasons for engaging with the Western notion of critical thinking literature on the conundrum in teaching a standalone critical thinking unit within the associate degree course in an Australian university. In this study I have used the term teaching staff and university lecturers interchangeably. This is because in some courses in an Australian university, not all teaching staff are lecturers. For example, they might be instructors brought in from industry or lab staff (University X 2022).

Research question

The central research question of this study was: How do teaching staff in Australian universities describe their lived experiences of teaching critical thinking? This study began with a description of participants’ lived experiences but expanded to an understanding of the participants’ lived experiences. This paper explores the university lecturers’ understandings of what critical thinking is and their perceptions, attitudes, and feelings towards the major concepts of critical thinking; how they practice critical thinking; and their lived experiences of teaching critical thinking at one Australian university. The central research question was guided by the university lecturers’ lived experiences of critical thinking in Australia which is fitting because it captures the very essence of the complex phenomenon under investigation. To answer the central research questions, I used a hermeneutic phenomenological approach that focuses on how the Australian lecturers interpret their world within their given context.

Research methodology and design

The data is drawn from research with three first-year undergraduate Australian university Ph.D. lecturers at a well-renewed research-intensive university in Australia. I chose to work with first-year Ph.D. university lecturers teaching in a first-year unit within the associate degree course, since they were the significant foci of exploration into teaching a standalone critical thinking unit. I especially wanted to show the challenges that the Australian teaching staff comes across whilst teaching critical thinking to the first-year students, but also, I wanted to highlight the relevance of the associate degree course in Australian tertiary education systems. According to Gale et al. (2013) the associate degree course “is different to other degrees in that the pathway into university includes the simultaneous study of university-level units with diplomas and AQF level 6 units” (p. 71). The associate degree course is unique on a national scale because it is designed as a preparatory program and allows students to transition into multiple disciplines (e.g. criminology, business, and marketing). One of the major purposes of developing the associate degree course was to offer a neoliberal solution to bridging the gap between vocational qualifications and undergraduate degrees and to provide access to domestic Australian students from a low social-economic status (SES) with a wider opportunity to enter higher education (Anderson & Boyle, 2019; Smith, 2013). There is an equity agenda for the Australian government to bridge this gap where the lower SES students can access higher education in Australia.

The three university lecturers in this study were teaching at the associate degree level within the Australian university. To understand their lived teaching experiences and life world, I used hermeneutic phenomenology, in particular the work of Heidegger, Gadamer, and Van Manen. The methodology is underpinned by Heidegger’s ontological philosophy of being part of this life world and Gadamer’s hermeneutic circle technique in interpreting the text, to unearth participants’ stories from the lens of the researcher (Eddles-Hirsch, 2015; Padilla-Díaz, 2015). Hermeneutic phenomenology as a methodology gives a voice to the people and focuses on their unique lived experiences as it is lived (Van Manen, 2016; Heidegger, 1982). In this case, the phenomenon is the lived of teaching critical thinking in one Australian university associate degree course. These experiences may be enacted and experienced differently by the individual Australian teaching staff. The hermeneutic approach allowed me to emphasise the subjective interpretation of texts and social phenomena which is contradictory to those studies that take an objective view in the construction of knowledge (Bloomberg & Volpe, 2015).

Data collection and data analysis approaches

Approach of data collection used in this study was a hermeneutic phenomenological repeated semi-structured interview. There were two semi-structured interviews at critical points in the trimester (University X teaching period). The data collection transpired through the two sets of semi-structured interviews designed for each participant (a total of six interviews), which provided a window into the exploration of teaching staff's lived experiences who were teaching critical thinking in the Australian university associate degree course.

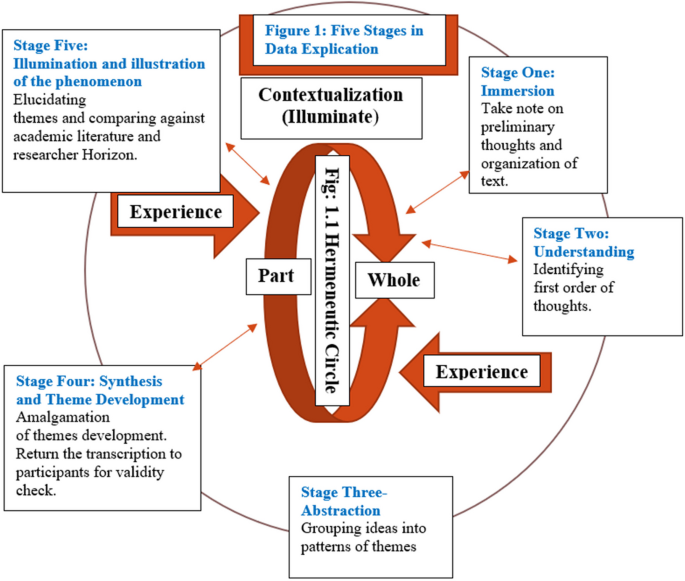

In fulfilling with the methodology embraced in this study, data analysis was used from phenomenological and hermeneutic circle principles. The hermeneutic circle aligns with the hermeneutic phenomenological research strategies and reinforces my interpretivist-constructivist philosophical views. In a simplified version of Gadamer (1994), Butler (1998), and Ajjawi and Higgs (2007), the hermeneutic circle is illustrated in Fig. 1.

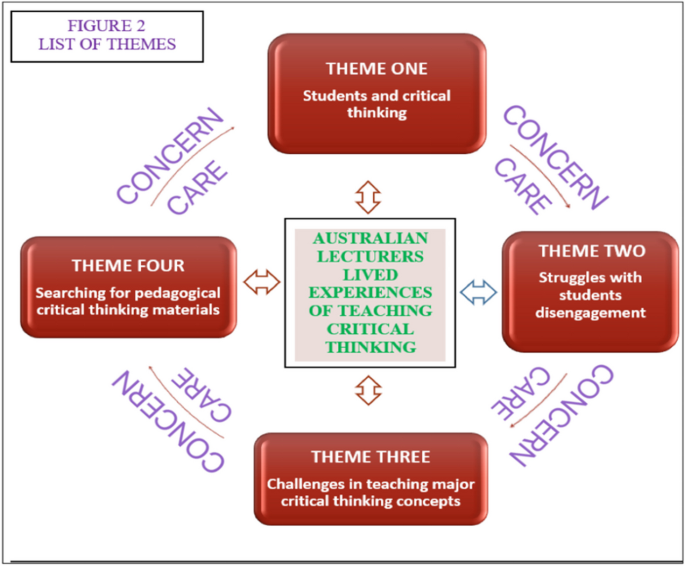

The hermeneutic circle is used in a circular rotation that moves between the parts (data which encompassed of interview and reflective field notes) and the whole (strengthening understanding of the phenomenon which comprises beyond the interviews such as other literature pertaining to the subject), each giving meaning to the other for understanding. There were five phases, and throughout each phase of the data analysis, there was a continuing interpretation of the text and the phenomenon of the Australian teaching staff’s lived experiences. Each research sub-question and the interview responses from the teaching staff were placed under the same coding steps (NVivo). These four themes—(1) students and critical thinking, (2) struggles with students’ disengagement, (3) challenges in teaching major critical thinking concepts, and (4) searching for pedagogical critical thinking materials—emerged from the data and met the research question objectives.

Overview of research findings

Four themes emerged based on the four research questions, and they should be read as one kind of response to that question to understand the whole (central research question). The findings may appear in the same order as the interview research questions; however, this was not the researcher’s intention. The four themes emerged based on the responses to individual research questions (refer to Fig. 2 lists of themes).

This paper now turns to the four themes which are exhibited, followed by Joan’s, Peter’s, and Sarah’s quotes to explain grounding in their lived experiences of teaching critical thinking in an Australian university. The hermeneutic phenomenology analysis of the findings can be obtained at University X library, Australia. In this paper, I have summarised the findings of participants’ quotes rather than the full hermeneutic phenomenology analysis of the findings.

Theme one: students and critical thinking

A key finding commonly conveyed in understanding and teaching critical thinking was Argument, Analysis, Evaluation, and Synthesis. Collectively, I viewed these four cognitive skills within the teaching of critical thinking as “students and critical thinking” as a particular theme (parts) to the whole. Joan, Peter, and Sarah described critical thinking as a process that involves Argument, Analysis, Evaluation, and Synthesis in the following texts.

Joan: This aspect of the phenomenon shows how Joan was using the terms Argument, Analysis, Evaluation, and Synthesis in the subsequent passage in the classroom setting:

Argument– is a set of claims, one of which is meant to be supported by the others. An argument offers a reason or reasons in support of a conclusion. We get students to practice breaking down popular arguments and because you can then understand what argument is, you can then break down all sorts of arguments around you, including academic arguments (Joan, interview one). Analysing – examine (something) methodically and in detail, typically to explain and interpret it (Joan, interview two). For this unit, it is around research (Joan, interview one). Evaluate – form an idea of the amount, number, or value of; assess (Joan, interview two); Once you’ve broken down those arguments, you’re able to apply critical thinking to evaluate what exactly it is that is being said, what might be some agendas that sit within it, what might be some biases, what might be some logical flaws or logical strengths (Joan, interview one). Synthesising – is combining different aspects of your ideas and research and the ideas of others – processing (Joan, interview two).

Joan acknowledged the importance of teaching critical thinking skills and considered them vital for students’ attainment at the Australian associate degree level, as she specifically mentioned:

How can we see critical thinking? We see it as an important skill that students need to be able to make sense of the world around them (Joan, interview one).

Here, Joan is referring to sense-making and critical thinking to understand “the world around them”, and this level of deep understanding is happening now in time and space in relation to what can be sensed and felt from the past, and it is an antecedent to understand what is to come. Heidegger’s philosophical ontological Sorge or care structure of Dasein focuses on beings towards the future. Joan felt that the role of having an open questioning mind is imperative, as she recalled:

I think about critical thinking as a way of understanding the world and that we need to have a questioning mind when we look at everything (Joan, interview one).

Joan’s teaching experiences continue to illuminate the process and strategies that she uses to move through the four fundamentals—“arguments, logic, science and psychology”—that are part of the sequence of teaching and developing critical thinking skills. Joan felt that moving through the “element[s] of critical thinking” would correlate to a greater student understanding of the concepts of critical thinking. The narrative is as follows:

So, we sort of move through four elements of critical thinking: arguments, logic, science and psychology. That is the framework, for example, our notion of critical thinking (Joan, interview one).

Joan’s perceptions of moving through the four stages of teaching critical thinking in the classroom brought positive benefits to her students. She thought that the teaching of critical thinking within these four elements—“Arguments, logic, science and psychology”—allowed her students to gain an in-depth understanding of the critical thinking subject and apply what they have learned in class within their daily life as well as becoming proactive independent learners and critical thinkers.

Peter’s outlook of teaching cognitive skills of Argument, Analysis, Evaluation, and Synthesis came from his philosophical, educational background. This is evidenced in the following extracts from our conversation:

Argument– is a set of claims, one of which is a conclusion and one or more which are premises used in support of this conclusion. Critical thinking is to question assumptions made by oneself and others. So, an example may be looking at a current news item and thinking about why they are presenting the information they are presenting (Peter, Interview two). Analysing – Questioning Arguments for soundness ensuring they are valid, and all the premises are true (Peter, interview two). Evaluate– To think critically we must evaluate arguments and not believe the first thing we read/hear. This involves understanding what is said but then questioning whether it is true, relevant to some standard (Peter, interview one). Making evaluative claims about the arguments, for example, that they are good/bad (this could be reasons other than their being sound, for example, there are bad consequences if we accept the conclusion) (Peter, interview two). Synthesizing– meant putting together ideas to form a (new) conclusion. This might include thinking about the part this story plays within a large background, or whether the presentation is biased in any way (Peter, interview two).

Peter felt confident that to make the unit more interesting, he ought to focus on making the critical thinking teaching material relevant, specifically targeting the student’s interests rather “than solely being about Argumentation”. Historically, philosophers such as Socrates, Plato, and Aristotle used the term “Arguments” to emphasise the theory of logic (DeBono, 1994). Peter used “Socratic Questioning” techniques in teaching critical thinking (Sahamid, 2016). Peter explicitly viewed and taught critical thinking from the philosophical position. As he alluded:

We take a Socratic understanding of critical thinking, where we consider whether the conclusions being presented to us are well supported with reasons. I come with a background in philosophy (Peter, interview one).

Sarah viewed critical thinking as Argument, Analysis, Evaluation, and Synthesis, and her lived experiences of teaching these cognitive skills show a deep connection with contemporary topics that are often talked about in the Australian media to promote engagement amongst her students. The following observations and comments capture her experiences in teaching critical thinking:

Argument– I find that learning to recognise the other side of Arguments is one of the most valuable skills I can encourage. For example, racism is one of our topic areas. Often the student cohort do not recognise casual or even overt racism especially connected to Australia (Sarah, interview one). Analysing – the ability to analyse texts so being able to actively read academic and other texts and ask questions about what you are reading. Students read relevant chosen academic journal articles and learn to identify the overall Arguments and evaluate the Arguments based on the evidence provided using principles of basic logic (Sarah, interview one). Evaluate– I find that students in general often tend to only see one side of a problem. For academic research, it is necessary to acknowledge both sides of an argument and look at each side to evaluate strengths and weaknesses critically (Sarah, interview one).

Sarah provided a specific example of these issues which related to Adam Goodes who is a famous Australian Aboriginal football player and discusses his lived experiences of racism (Ashton, 2019). Here, Heidegger’s phenomenological concept of Dasein is apparent as Sarah was placing her students into a specific time and space in history where their students had no choice except to be engaged in part of that world (Göpffarth, 2020; Heidegger, 1982). Sarah continues to draw on pedagogical strategies in her teaching that are making connections with popular culture and current issues pertaining to Australia but also all over the world. For example:

So here in a practical sense what we have tried to do is to get students to look at problems (issues such climate change, marriage equality, racism, cricket cheating scandal) and begin to frame the problem using research into the various arguments put forward for a particular side. So, we might pick teams and have a debate (Sarah, interview two).

Sarah refers to a well-publicised cheating scandal which occurred during a cricket match. Holmes (2018) explains that Cricket Captain Steve Smith and Vice-captain David Warner were allegedly caught in a ball-tampering saga. Sarah draws heavily on sport-related issues in pedagogical teaching strategies to create debates amongst her students. Sarah continues to express the importance of teaching her students about backing up claims with scholarly evidential work of published authors:

In their research it’s important that students come to understand the various positions an argument can take and to challenge their own assumptions through needing to find scholarly evidence to back up positions. So, students are doing all these functions in their research and in putting forward arguments and counterarguments and then developing and using these skills in their essays (Sarah, interview two).

Reflection

Sarah uses these teaching activities to show students how to make “counter arguments” and that they must illustrate these skills in their essay. She suggests that the teaching strategies and activities that she fosters using interaction between herself and her students as well as students to students are socially constructed helping her students to share their past and present experiences and challenging her students’ own assumptions and thoughts which requires questioning what is being offered, and reformulating conceptions through her. Heidegger (1982) theory of the hermeneutical concept of Sorge is concerned with care or being interested in other human beings. Joan, Peter, and Sarah saw care as a way of being in this world with their students. Whilst the lecturers expressed care, they did not use words such as “care” or “caring” explicitly in their statements. I have used the hermeneutic approach to infer this from what the lecturers did not say, by searching for hidden clues (e.g. nonverbal cues and behaviours including gestures and tone of voice), phrases, words, and statements that showed care and concerns towards their students (Gadamer, 1994), for example, highlighting students’ weaknesses and areas of improvement for individual students and selecting or creating critical thinking activities that would interest students and their educational needs. Heidegger (1982), in “Being and Time”, declares that the truth of being human is Sorge or care. As university lecturers, we do not go around saying, “I care for critical thinking or for students”. Care is something that we do unconsciously as qualified lecturers, which is part of our professional ethical code or habitus, and it is rarely discussed in the teaching of critical thinking or in academic critical thinking literature (see e.g. Heard et al., 2020; Willingham, 2019).

This is an illustration of Gadamer’s hermeneutic circle approach in deciphering data and uncovering meaning in hermeneutic study. However, my position is that without care, one cannot be a good critical/constructive university lecturer but still can be a great critical/constructive thinker. The initial theme of students and critical thinking is the first part of the whole in understanding the lived experiences of teaching critical thinking from the first-person world view of Australian lecturers. This theme is related to the whole, which is the care and concern for students and for teaching a standalone critical thinking unit within the associate degree course in an Australian university. I have moved in the hermeneutic circle, between a part of the text (students and critical thinking) and the whole (care and concern for teaching critical thinking) of the text, to prove truth by uncovering phenomenon and understand them. For example, participants showed care when they said that “I find that students in general often tend to only see one side of a problem” and/or students lack critical thinking skills. Therefore, “we see it as an important skill that students need to be able to make sense of the world around them”; and how to best teach these four cognitive domain skills (Synthesis, Analysis, Arguments, and Evaluating) to their students is a fundamental concern to the participants. The hermeneutic circle is a process of understanding the interview transcription by reference to the separate parts, along with my understanding of each distinct part of teaching critical thinking, to understand the whole.

Theme two: struggles with students’ disengagement

The participants’ responses expressed issues such as students not submitting unit assessment on time, students not attending classes or seminars, low motivation, and/or low attendance. Together, these five phenomena incorporate what I saw as “struggles with student’s disengagement” as a particular theme in teaching critical thinking. Joan, Peter, and Sarah faced a personal struggle with students’ disengagement, which ultimately affected students’ learning. A common thread of these teaching strategies is that they act as prompts leading to critical analysis of the new information compared to what is already known in the critical thinking literature. Interviewees explained their lived experiences in the subsequent narrative.

The students’ disengagement exposed Joan’s personal struggle in teaching critical thinking. Joan’s concern for the students’ learning and their development of critical thinking is revealed as follows:

The main difficulty we encountered is low attendance. Teaching students, particularly non-traditional students who are coming in on an alternative pathway, the biggest challenge we have is attendance for students, not actually being present in the seminars and in the lectures to be able to engage with the critical thinking concepts fully. And then as a result they are not going to understand (Joan, interview one).

Peter’s lived experiences in teaching critical thinking show that he was still struggling with engaging all his students. Peter felt that if students were not engaged in the critical thinking unit, then it was a struggle to teach and motivate students to foster their critical thinking skills. As demonstrated by Peter:

If the class is generally motivated, then some good discussions can get going (Peter, interview one). The critical thinking concept is a bit dry for students – it is often hard to engage students. I suspect this is because they are not interested in the subject matter (Peter, interview two). One challenge I do have is to keep students engaged because the subject is quite dry (Peter, interview one).

The theme of Sarah’s interview responses revealed that she was struggling with low student engagement which impeded the development of critical thinking skills. The following quote exemplifies the difficulty for Sarah to offer the one-on-one support required to help students overcome barriers to attendance:

Yes! Attendance is a problem. At the beginning of the term the attendance is about 80–90 percent (week 1–3). However, towards the middle and/or the end of the term the attendance drops around 50 percent. Out of the group of 20 students that are supposed to attend the seminar around 5 would turn up to class towards the end of the unit. The attendance fluctuates during the semester (Sarah, Interview one).

I do think there is a bit too much material to cover. There are lots of articles and materials to read in such a short time for the students (Sarah, interview two). Critical thinking can be a somewhat dry topic, so we try to make it relevant using examples from the current news and popular culture. One specific example I’ve used is to discuss racism using political cartoons such as the Serena Williams cartoon from Charlie Hebdo (Sarah, interview two).

Reflection

Participants’ personal struggles with students’ disengagement in practicing critical thinking were revealed. This is a result of the current Australian government’s ideological pressures in higher education which have caused increased challenges for Joan, Peter, and Sarah including a commodified critical thinking unit curriculum, time constraints, and increased surveillance of participants’ workload and outputs. All of which affect teacher-students’ relationships, hindering students’ learning outcome. The primordial nature of our being with others is shown in the phenomenon of the participants’ relationships with their students and in the relationships between students, which are a fundamental aspect of developing students to think critically within the unit. The relational nature of being with others is experienced as of importance to Joan, Peter, and Sarah for their students’ learning and well-being that goes beyond the classroom. The teacher-student relationship mattered differently to each participant. Joan’s relationship with her student was constricted by students failing to respond to her emails regarding submitting unit assessment on time and by their non-attendance. Peter’s relationship with his students was restricted by not being able to have a critical discussion with students if students disengaged or did not attend lectures and seminars. He believed that in developing students to think critically, then social interactions between students and between the teacher and student are necessary; otherwise, it is a struggle to have a productive discussion about real-world social issues that are affecting our lives and which require possible solutions from his students. Sarah’s relations with her students were constrained by low engagement affecting in the delivering of the unit materials within the course structure, and students’ learning in the development of critical thinking skills. Whilst participants endured their personal struggles, I was struck by Joan’s, Peter’s, and Sarah’s depth of caring and concern in teaching critical thinking. These lived experiences are best labelled as “care” and/or “caring” qualities. Joan, Peter, and Sarah showed Heidegger’s concept of Sorge (caring) emotions consistently throughout the interviews (Heidegger, 1982). Heidegger (1982) theory of the hermeneutical concept of Sorge is concerned with care or being interested in other human beings. Joan, Peter, and Sarah saw care as a way of being in this world with their students.

The findings of this study revealed some similarities to the model of Concern in relation to understanding the teaching of critical thinking in literature. Heidegger (1982) and Donnelly (1999) stated that to care is also a means of concern. In this context, teaching becomes part of authentic relations as Australian lecturers showed in the data, and they sincerely acted out their caring natures and their concern for their students in teaching critical thinking (Brook, 2008). However, my claim is that Heidegger (1982) notion of Sorge (care or concern) was important in understanding the lived experiences of Australian lecturers’ teaching of critical thinking. I saw the caring and concern nature towards other beings as an essential characteristic in teaching critical thinking and in the development of students’ critical thinking skills. However, my stance is parallel with the literature of Dewey (1910/1933) that without caring or concern characteristic and moral integrity, people can still be an effective critical/constructive thinker. As a result, the notion of care and emotion must not be applied in relation to the theoretical and conceptual framework or model of critical thinking.

The hermeneutic circle allowed me to comprehend participants’ lived experiences along with my understanding of each of these distinct separate parts of teaching critical thinking, to recognise the whole in relation to the core struggles of critical thinking in a neoliberal work environment in Australia.

Theme three: challenges in teaching major critical thinking concepts

The theme “challenges in teaching major critical thinking concepts” (parts) contains an overlapping phenomenon to theme two. However, theme three provides additional in-depth information on the challenges of teaching critical thinking that was not revealed in theme two. This is another example of how the hermeneutic circle helps in understanding the parts/whole structure of hermeneutic phenomenological research and reveals experiences that otherwise would not be noticed.

The interviewees shared their lived experiences with these challenges.

Joan’s emotions and her perceptions, attitudes, and feelings towards the critical thinking concepts give a cognitive mental picture of her emotional state (Hagenauer & Volet, 2014; Janssen, et al., 2019). The narrative that follows recounts Joan’s experiences in a subject she loved:

I guess I just feel quite excited about the unit where you get to do such a lot of discussion about Argument. I think that’s wonderful. I feel quite excited about it. I did write the unit, so I think that that probably feeds into why I feel so passionate and excited about it. But my perception is that I’m quite excited; that is my attitude towards it (Joan, interview one).

Peter’s perception of his lived experiences towards the major concepts of critical thinking provided a unique portrait of his emotional state of mind. Peter was portraying his optimism and positivity but, by the same token, concerns. Peter’s experience of engagement is manifested as satisfying and positive:

I think they are quite good. Students are taught standard ways to argue and some standard fallacies. It can be a bit dry for students, whose primary purpose at university is to provide formal Arguments (Peter, interview one).

Sarah had taught the Critical Thinking and Problem-Solving unit for many years, yet she found the content of inductive and deductive reasoning very challenging to teach. Sarah believed that her own lived experiences were intertwined with the concept of critical thinking, giving her the opportunity to share her practical knowledge of her own life experiences as a basis for the development of students’ critical thinking skills which provided a context when explaining difficult critical thinking concepts to her students. Sarah shared her concerns:

There are three (inductive reasoning, deductive reasoning, and formal Arguments) concepts that I think students find most difficult. What I mean by formal Arguments is being able to form an academic Arguments in a paper which is a fundamental skill for students, and this is what we are really aiming for during the unit so that by the end of the unit, students have really begun to develop this skill (Sarah, interview two).

Reflection

All three participants found that the formal and informal logical fallacies or deductive and inductive forms of argument concepts were most challenging to teach within the associate degree course. Theme three is directly associated with the whole (central research question). The clockwise rotating structure of moving in the hermeneutic circle, between a part of the text (challenge in teaching major critical thinking concept disengagement) and the whole (for students’ academic development and concern for teaching critical thinking) of the text, establishes truthfulness by revealing the phenomena. Heidegger’s concept of Sorge or care here is about how participants’ students’ well-being became the major priority and how they directed their communication and attempts to build or maintain relationships with their students in the development of critical thinking, even though they were facing personal barriers and challenges.

The concern is how do you successfully teach these complex, multidimensional concepts of critical thinking to students when they are entering the unit with such a low academic rigor compared to other degree courses in an Australian university in a short amount of time? These concerns add deeper meaning of the whole, the essence of what teaching critical thinking is like for lecturers in Australian universities. The hermeneutic circle conceptional framework helped in understanding participants’ lived experiences, incorporating my early comprehension of the parts of the challenges in teaching a standalone critical thinking unit, to understand the whole.

Theme four: searching for pedagogical critical thinking materials

The Australian university lecturers’ responses discussed the materials that they employed in teaching critical thinking. They talked of not having a set textbook, using articles from various sources including non-proscriptive textbooks, and sourcing chapters from academic publications. The accumulation of these four sources of materials combined is what I viewed as “searching for pedagogical, critical material” (Dwelling) as a distinct theme in teaching critical thinking. Participants incorporated the notion of dwelling in separate but notable ways. The responses from participants exposed the final theme, which was one of the novel features of the course design.

Joan stated that unlike other University X course structures where a prescribed textbook was compulsory, this was not the case for the Critical Thinking and Problem-Solving unit within the associate degree foundation program. The following comment from Joan provides insights on a critical thinking unit free from a prescribed textbook:

So, we don’t have a textbook. We use a range of different articles from different textbooks and, different to other units, they’re all very practical. We use academic articles, chapters from books that have activity-based elements. So, in the first week we just looked at critical thinking as a notion they read with chapter by Verlindern about what critical thinking is. They are very practical, accessible chapters from books that have activities, which is different to any other unit I teach where we don’t have that at all (Joan, interview one).

Peter searched for diverse materials and resources to develop his students’ critical thinking skills as there was no prescribed textbook for the Critical Thinking and Problem-Solving unit. Peter’s experiences included:

Mainly textbooks. There are also video clips that are used. I get them to do different activities. For example, work in pairs/groups, write on butcher’s paper, and write answers to questions (Peter, interview one).

Sarah used learning materials for her students that comprised a balance of technological activities and traditional chapters from different textbooks and journals. The following comment from Sarah gives detailed insights of the unit free from a prescribed textbook:

We often use video material to help explain difficult concepts as an adjunct. As we have a diverse student cohort studying not only education but also many different Arts units, we make sure that we provide a wide variety of current issues that might be of interest not only for seminar teaching but also in assessments (Sarah, interview one).

Reflection

These four responses in relation to resources—no prescribed unit textbook, searching for videos, probing for different journals, and looking for different chapters from books—were connected to what I saw as searching for pedagogical, critical thinking materials (parts) in teaching critical thinking. In the light of above comments, being free from a critical thinking unit prescribed textbook gave lecturers autonomy and independence to select a variety of materials and activities to build relationships between the teacher and students and amongst the students themselves and to share lived experiences in the associate degree course in relation to teaching the critical thinking unit. What was common in the findings was that all participants understood that their students were entering the course from different backgrounds, had different knowledge and skill sets, with different experiences and interests, and they used the critical thinking activities to make connections in building their students in the development of their critical thinking skills.

The participants’ lived experiences of teaching critical thinking show that they were using the critical thinking activities in a meaningful and integrated context not in an isolation to foster critical thinking skills. This final theme shows how the participants developed an authentic learning environment for their students and how they dwelled in the asynchronous and synchronous settings in teaching critical thinking at an Australian university which is directly linked to the whole. The findings of this study align with the Heideggerian hermeneutic phenomenology theory of Dwelling in comprehending the teaching of critical thinking in literature. Heidegger’s theory of dwelling helped me to think through the very essence of teaching critical thinking.

Implication and limitations

The feelings testified by the Australian lectures in this study demonstrated their lived experience of struggles and concerns of teaching a standalone critical thinking unit within the associate degree course in an Australia tertiary education. As such, they may help us to better understand specific points of concerns regarding the design of future critical thinking unit for the associate degree courses. The theme of “struggles with students” disengagement and the “challenges in teaching major critical thinking concepts” suggest that it would be challenging to foster critical thinking skills if students’ fail to show up to class or are not engaged, are not motivated, and are unwilling to complete homework and/or participate in class. This is not just an Australian tertiary education problem, but it is a worldwide issue that has eminence implication for teaching (lecturers) and learning (students).

Considering this small-scale study with only three participants from an Australian university being interviewed, they cannot represent all Australian lecturers in higher education contexts that are teaching critical thinking within the associate degree course. It is imperative to understand that hermeneutic phenomenology may not generalise the data beyond this population and may not detect the entire themes under investigation and some themes may be unexplored and/or neglected because of the complex nature of the subject and the research methodology (Groenewald, 2004; Bentz & Shapiro, 1998). Therefore, future study can focus on large group of lecturers teaching critical thinking from different discipline and courses from multiple universities to gain a deeper insight into how critical thinking is actually being taught and whether or not these similar feelings occur in different contexts and with diverse sample sizes.

Discussion and conclusion

I focused on the movement through the hermeneutic circle between the researcher’s horizon, literature review, and the findings. I structured the central findings and discussion of teaching critical thinking emerging from interpreting the qualitative data. By finding the very essence of teaching critical thinking in Australian universities. These three (Dwelling, Sorge, and Concern) concepts in teaching of critical thinking emerged from the research findings and appeared at different levels. The essence revealed in this study should be viewed in relation to one another. Aligned with hermeneutic circle data analysis procedures, if any parts of the essence (e.g. Dwelling, Sorge and Concern) alternates or changes, then this ultimately will affect the other parts and the whole in relation to the understanding of the Australian lecturers’ lived experiences of teaching critical thinking. The theoretical framework of Sorge failed to align with critical thinking literature. The findings of the current study do not support the previous research of Perkins et al. (1993) and Ennis (1996). A plausible explanation for this might be that the participants in this study saw the notion of care as not being necessary to be an effective critical thinker. Therefore, participants have avoided using Perkins et al.’s (1993) critical thinking disposition and Ennis (1996) correlative disposition model in teaching critical thinking within the associate degree course in an Australian university.

Based on a hermeneutic phenomenological study, four main difficulties in teaching and learning of critical thinking were evident in all three lecturers. These were (1) students and critical thinking, (2) struggles with students’ disengagement, (3) challenges in teaching major critical thinking concepts, and (4) searching for pedagogical critical thinking materials that emerged from the data. These teaching and learning issues found have deep consequences for universities around the world (e.g. United States of America, New Zealand, Canada, and the UK), policymakers, business leaders, and the public. Therefore, medias, governments, and business leaders globally must understand how difficult it is to teach critical thinking and why some students may not have an adequate level of critical thinking skills after graduation to get employment which is neither the sole burden of the university lecturers’ nor the universities. This is a universal educational issue and is a matter of teaching and learning concern worldwide in tertiary education. Therefore, it would be unethical, unjust, and unfair to assume that only university lecturers are solely responsible for fostering critical thinking skills of students, and some of these responsibilities must be taken by students themselves (turning up to lectures and seminars) and the government’s policy agenda (consequences of massification), as well as further critical thoughts are needed on the notion of universities students’ selection policy entering tertiary education.

Data availability

All the data gathered and used during the study are openly available from Deakin University Liberary.

References

Ajjawi, R., & Higgs, J. (2007). Using hermeneutic phenomenology to investigate how experienced practitioners learn to communicate clinical reasoning. Qualitative Report, 1(4), 621–638.

Anderson, J., & Boyle, C. (2019). Looking in the mirror: Reflecting on 25 years of inclusive education in Australia. International Journal of Inclusive Education, 23(7–8), 796–810.

Ashton, K., (2019). Adam Goodes “cut down” by racist booing because he was powerful, says commentator Charlie King. The ABC radio. Retrieved from https://www.abc.net.au/news/2019-07-21/adam-goodes-faced-racism-because-he-was-powerful-charlie-king/11328552

Australian Centre Education Research. (2019). The Australian Qualifications Framework: Revision or re-vision? 1(2), 71–72. Retrieved from https://www.dese.gov.au/quality-and-legislativeframeworks/resources/revision-or-re-vision-exploring-approaches-differentiation-qualification-types-australia.

Australian Council for Educational Research. (2019). The Australian Qualifications Framework: Revision or re-vision? Retrieved from https://www.dese.gov.au/quality-and-legislativeframeworks/resources/revision-or-re-vision-exploring-approaches-differentiation-qualificationtypes-australia .

Australian Qualifications Framework. (2013). Australian Qualifications Framework Council. 1(2), 1–111. Retrieved from www.aqf.edu.au .

Bentz, V. M., & Shapiro, J. (1998). Mindful enquiry in social research. Sage.

Bloomberg, L. D., & Volpe, M. F. (2015). Completing your qualitative dissertation: A roadmap from beginning to end. Sage.

Brook, A. (2008). The potentiality of authenticity in becoming a teacher. Philosophy Papers and Journal Articles, 1(1), 1–18.

Butler, T. (1998). Towards a hermeneutic method for interpretive research in information systems. Journal of Information Technology, 1(13), 285–300.

Danvers, E. (2015). Criticality’s affective entanglements: Rethinking emotion and critical thinking in higher education. Gender and Education, 28(2), 282–297.

DeBono, E. (1994). DeBono ’s Thinking Course (rev ed.). New York, America.

Dewey, J. (1910/1933). How We Think. Lexington, MA: D.C. Heath & Co.

Donnelly, J. F. (1999). Schooling Heidegger: On being in teaching. Teaching and Teacher Education, 15(8), 33–49.

Eddles-Hirsch, K. (2015). Phenomenology and educational research. International Journal of Advanced Research, 3(8), 251–260.

Ennis, R. (1996). Critical thinking dispositions: Their nature and assessability. Informal Logic, 18(2–3), 165–182.

Facione, P. A. (1990). Critical thinking: A statement of expert consensus for purposes of educational assessment and instruction – The Delphi Report. California Academic Press.

Gadamer, H.-G. (1994). Truth and Method. London: Continuum Press.

Gale, T., Hodge, S., Parker, S., Rawolle, S., Charlton, E., Rodd, P., Skourdoumbis, A., & Molla, T. (2013). VET Providers, Associate and Bachelor’s Degrees, and Disadvantaged Learners. Report to the National VET Equity Advisory Council (NVEAC), Australia. Centre for Research in Education Futures and Innovation (CREFI), University X, Melbourne, Australia. Retrieved from www.d.edu.au/arts-ed/efi/pubs/VET-associatebachelor-degrees-disadvantaged-learners.pdf

Go8 (2021). Go8 Submission to the Australian Strategy for International Education 2021–2030. Retrieve from https://go8.edu.au/go8-submission-to-the-australian-strategy-for-internationaleducation-2021-2030 .

Göpffarth, J. (2020). Rethinking the German nation as German Dasein: Intellectuals and Heidegger’s philosophy in contemporary German New Right nationalism. Journal of Political Ideologies, 25(3), 248–273.

Groenewald, T. (2004). A phenomenological research design illustrated. International Journal of Qualitative Methods, 3(1), 42–55.

Guba, E. G., & Lincoln, Y. S. (1994). Competing paradigms in qualitative research. In N. K. Denzin & Y. S. Lincoln (Eds.), Handbook of qualitative research (pp. 105–117). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage. Retrieved from https://www.uncg.edu/hdf/facultystaff/Tudge/Guba%20&%20Lincoln%201994.pdf

Hagenauer, G., & Volet, S. (2014). I don’t think I could, you know, just teach without any emotion: Exploring the nature and origin of university teachers’ emotions. Research Papers in Education, 29(2), 240–262.

Heard, J., Scoular, C., Duckworth, D., Ramalingam, D., & Teo, I. (2020). Critical thinking: Definition and structure (p. 1–7). Australian Council for Educational Research. Retrieved from https://research.acer.edu.au/ar_misc/38 .

Heidegger, M. (1982). The basic problems of phenomenology. The Journal of Theological Studies, 34(1), 366–368.

Heidegger, M. (1996). Being and Time. State University of New York Press.

Holmes, T. (2018). Ball-tampering scandal: Cricket Australia under mounting scrutiny over team culture. The ABC. Retrieved from https://www.abc.net.au/news/2018-04-01/cricket-australiaunder-mounting-scrutiny/9608638

Janssen, E., Mainhard, T., Buismanb, R., Verkoeijen, P., Heijltjes, A., Peppenc, L., & van Gog, T. (2019). Training higher education teachers ‘critical thinking and attitudes towards teaching it. Contemporary Education Psychology, 1(58), 10–322.

Lai, E. R. (2011). Critical thinking: A literature review. Pearson’s Research Reports, 6(1), 4–48.

Noddings, N. (1984). Caring. A feminine approach to ethics & moral education. University of California Press.

Noddings, N. (2002). Educating moral people. A caring alternative to character education. Teachers College Press.

Padilla-Díaz, M. (2015). Phenomenology in educational qualitative research: Philosophy as science or philosophical science? International Journal of Educational Excellence, 2(1), 101–110.

Perkins, D. N., Jay, E., & Tishman, S. (1993). Beyond abilities: A dispositional theory of thinking. Merrill-Palmer Quarterly, 39(1), 1–21.

Sahamid, H. (2016). Developing critical thinking through Socratic questioning: An action research study. International Journal of Education & Literacy Studies, 4(3), 62–72.

Smith, H. (2013). ALTC Teaching Fellowship Improving tertiary pathways through cross sectoral integration of curriculum and pedagogy in associate degrees, pp. 2–251. Rederived from https://ltr.edu.au/resources/Smith_report_RMIT_2013.pdf

University X. (2020). Attendance policy. Retrieved from http://public.universityXcollege.edu.au/Documents/Attendance%20Policy.pdf

Van Manen, M. (2016). Phenomenology of practice: Meaning giving methods in phenomenological research and writing. Routledge.

Weinstein, M. (1991). Critical thinking and education for democracy. Educational Philosophy and Theory, 23(2), 9–29.

Wilkie, D. (2019). Employers say students aren’t learning soft skills in college. The Atlantic. Retrieved from https://www.theatlantic.com/employers-say-students-arent-learning-soft-skills-in-college/2019/05/

Willingham, D. (2019). How to teach critical thinking. Education Frontier/Occasional paper series, a paper commissioned by the NSW Department of Education, 1–16. Retrieved from http://www.danielwillingham.com/uploads/5/0/0/7/5007325/willingham_2019_nsw_critical_thin king2.pdf

Acknowledgements

I would like to express my appreciation to the faculty of arts and education lecturers who participated in this study. In addition, I would like to express my gratitude to my Ph.D. supervisors.

Funding

Open Access funding enabled and organized by CAUL and its Member Institutions

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethical approval

Ethical approval for this research was obtained from the University X, Victoria, Australia Human Research Ethics Committee and from relevant ethics committees at the University X campus site from which data were collected. I used a pseudonym to disguise the participants’ name and the Australian university to maintain their identity.

Competing interests

The author declares no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Manning, M.N.J. University lecturers’ lived experiences of teaching critical thinking in Australian university: a hermeneutic phenomenological research. High Educ 88, 2057–2073 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10734-024-01200-6

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10734-024-01200-6